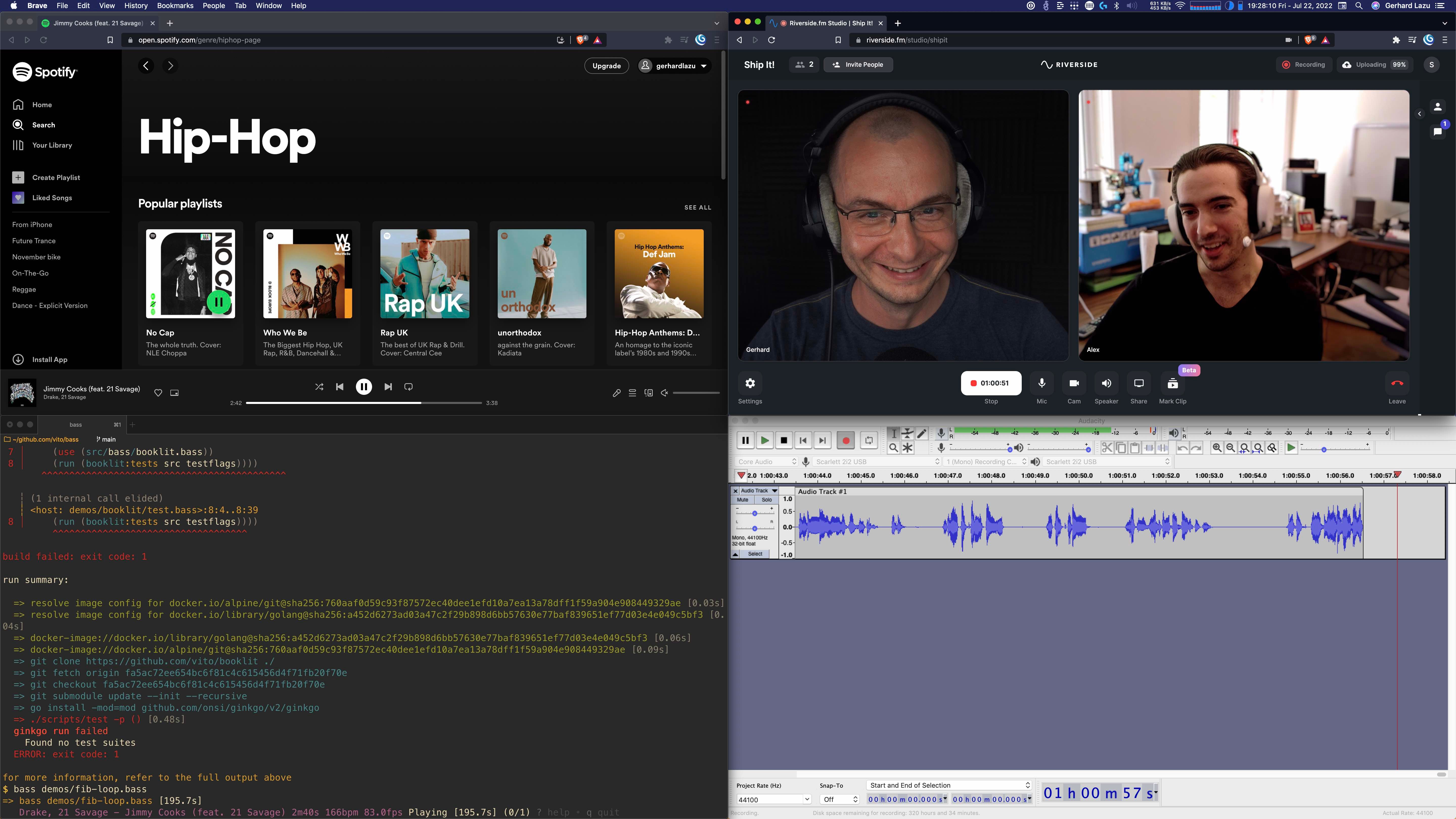

Our today’s guest spent 4 days building a feature for his side project so that we could ship it together on Ship It!, while recording. The feature is called rave mode, and the context is Bass, an interpreted functional scripting language written in Go, riffing on the ideas of Kernel & Clojure. When the local build runs, you can now press r to synchronise the beats of your currently playing Spotify track with the build output. For a demo, see bass v0.9.0 release.

Please welcome Alex Suraci, a.k.a. vito, the creator of Concourse CI and Bass.

This episode is dedicated to the late John Shutt, the creator of Kernel.

Your ideas continue in Bass.

Thank you for getting them out into the world.

Featuring

Sponsors

Sourcegraph – Transform your code into a queryable database to create customizable visual dashboards in seconds. Sourcegraph recently launched Code Insights — now you can track what really matters to you and your team in your codebase. See how other teams are using this awesome feature at about.sourcegraph.com/code-insights

Sentry – Working code means happy customers. That’s exactly why teams choose Sentry. From error tracking to performance monitoring, Sentry helps teams see what actually matters, resolve problems quicker, and learn continuously about their applications - from the frontend to the backend. Use the code SHIPIT and get the team plan free for three months.

Retool – The low-code platform for developers to build internal tools — Some of the best teams out there trust Retool…Brex, Coinbase, Plaid, Doordash, LegalGenius, Amazon, Allbirds, Peloton, and so many more – the developers at these teams trust Retool as the platform to build their internal tools. Try it free at retool.com/changelog

Akuity – Akuity is a new platform (founded by Argo co-creators) that brings fully-managed Argo CD and enterprise services to the cloud or on premise. They’re inviting our listeners to join the closed beta at akuity.io/changelog. The platform is a versatile Kubernetes operator for handling cluster deployments the GitOps way. Deploy your apps instantly and monitor their state — get minimum overhead, maximum impact, and enterprise readiness from day one.

Notes & Links

- Concourse CI

- See shipit.show/9 notes for the RabbitMQ v3.8 CI/CD pipeline from 2020

- Concourse core roadmap: towards v10 - written by Alex 3 years ago

- 🎬 Getting Started with Concourse CI - Dr. Nic Williams, Stark & Wayne - October 2016

- Faux-O talk - Gary Bernhardt

- The Kernel Programming Language

- Bass bassics

- The bass shipit file that ships Bass

- bass v0.9.0 release - the one that we shipped while recording this episode

- booklit.page - a tool for building static websites from semantic documents

- Package repository size/freshness map

Chapters

| Chapter Number | Chapter Start Time | Chapter Title | Chapter Duration |

| 1 | 00:00 | Welcome | 01:18 |

| 2 | 01:18 | Sponsor: Sourcegraph | 03:04 |

| 3 | 04:22 | Intro | 04:35 |

| 4 | 08:57 | The ONLY Concourse view | 01:09 |

| 5 | 10:06 | The design | 01:09 |

| 6 | 11:15 | Biggest early challenge at Concourse | 04:37 |

| 7 | 15:52 | To work on Concourse | 01:18 |

| 8 | 17:10 | Bass | 02:05 |

| 9 | 19:15 | What's better than declarative? | 02:45 |

| 10 | 22:00 | Commands | 02:19 |

| 11 | 24:19 | Multiple themes?? | 01:57 |

| 12 | 26:15 | What's a thunk? | 00:33 |

| 13 | 26:48 | Space invaders | 05:34 |

| 14 | 32:23 | Sponsor: Sentry | 00:53 |

| 15 | 33:16 | Run time compiler | 01:55 |

| 16 | 35:10 | Where does it all run? | 03:21 |

| 17 | 38:31 | Github runner | 01:54 |

| 18 | 40:25 | The Ship It file | 04:15 |

| 19 | 44:40 | Rave mode | 10:39 |

| 20 | 55:20 | Sponsor: Retool | 00:52 |

| 21 | 56:12 | Sponsor: Akuity | 02:09 |

| 22 | 58:21 | Let's ship it | 10:22 |

| 23 | 1:08:43 | Should caching be close? | 03:36 |

| 24 | 1:12:20 | Conway's game of life | 01:43 |

| 25 | 1:14:02 | What did you enjoy the most? | 02:22 |

| 26 | 1:16:24 | Nix and Bass | 01:30 |

| 27 | 1:17:53 | 0.1.2 | 10:10 |

| 28 | 1:28:04 | Wrap up | 02:26 |

| 29 | 1:30:29 | Outro | 01:01 |

Transcript

Play the audio to listen along while you enjoy the transcript. 🎧

I’ve been looking forward to this for some time now… Seven months, to be more precise. And we have lots to talk about - Concourse CI, Bass, the wider CI/CD problem space… And we have just the right person for this today. Alex, welcome to Ship It.

Thanks. Good to be here.

So eight years ago, I think, if I’m counting correctly, you had the idea of the CI/CD system that was different from everything else that came before. We all know it as Concourse CI. At the time, what made you believe that the world needed Concourse?

It’s a good question, because there was already a lot of like CI/CD systems out there. And there’s even more every day, it seems like… But what really drove it was, we were trying to use Jenkins, and we were trying to use that to automate all of Cloud Foundry, which was like a massive pipeline. We were gluing together plugins and trying to keep that thing running, and it was kind of its own separate job, just keeping Jenkins in check. And meanwhile, we were building out this platform that was driven by like declarative YAML. You’d just say what you want, and then you’d tell it to go, the system figures it out… And the thing that we were using to drive that was very much the opposite. So I wanted to try and take what we learned from that and apply it to CI/CD.

[05:59] I think the main motivation was having just clarity in how the whole system works, and being able to trust it, and not worrying about if that VM gets struck by lightning and dies, we have to like spend another week just getting everything – like, clicking the right buttons, getting it up once again. So that’s what brought Concourse to the world, really… Myself and Chris Brown raging at Jenkins.

Chris Brown… We actually worked together; we were in the London office, and we were also struggling with Jenkins big time, and GoCD as well. We tried a couple, we went through a phase where we’d been trying different CI’s, and none of them were quite cutting it. We have the problem of the data services, Cassandra and MySQL, and Redis and Rabbit MQ… How do you package them in a way that platform teams can use them to enable developer teams to just get on with application code and just provision services? So how do you package that, how do you upgrade? And you obviously have to test all the things. How to get CVEs out quickly enough? And a bunch of concerns like that. How do you scale, how do you degrade gracefully? It was such a pain. And interestingly, Jenkins was one of those services.

And I remember Tammer at the time, he was who he was the PM on the Pivotal side, and he was saying, “Hey, if the product that we’re packaging doesn’t work, let’s not try and work around these shortcomings by automation.” I remember that very clearly.

So Jenkins, we were very intimate of how it worked, because we ourselves had to do it for other customers, and we were using it, we were like dogfooding it, and it was failing in so many weird and wonderful ways. And then Concourse came along… Hm, nice. Chris Brown… Yeah, I haven’t talked to him in years. How is he these days? Do you know about him? Hey, Chris, if you’re listening, I’m saying hi. I hope you are.

Yeah, he’s just, you know, living it up at stripe, doing a lot of – he’s actually working on their workflow engine team, which uses Temporal under the hood, which is kind of…

Ooh, interesting.

Yeah, kind of a funny coincidence, because they showed up on like GitHub discussions a while back, saying how they use Concourse to deliver Temporal.

Wow.

And they linked to this article, it was from San Diego Times or something, and the screenshot in the article was not Temporal, it was their dashboards, their Concourse dashboards that deliver Temporal.

So that’s crazy. What a small world.

Yeah, the places that Concourse web UI shows up is always interesting.

Okay, okay. So I think one of the things that made Concourse so memorable, and so – it had a face, and the face was the pipeline. I don’t think – at least in my experience, I haven’t seen any other CI that did pipelines or that does pipelines, the views of a pipeline as good as Concourse did it. Whose idea was that to make that the only, the default Concourse view, and the only Concourse view?

Well, it’s since gotten a little more complicated. There’s like the whole dashboard that wraps it and like compresses it into like a thumbnail view thingy, and you click into that… But ultimately, the UI that we have today was like myself and Amit Gupta, just like messing around after hours at Pivotal and trying to come up with what is a good visualization.

The first stage was actually just using Graphviz and just like feeding it like a DAG, and then seeing what it renders. And it did interesting things, but it couldn’t quite express like fan/out fan in, and all the different kinds of things. So that turned into just banging my face against JavaScript until things mostly worked, and then fixing whatever bugs came up.

Yeah. You’re right. You’re actually right. You mentioned the collection of pipelines - that was added later on. I remember it for like many years, like back in the time like when it first came out… It was just a pipeline view and that kept improving. I’ve really liked like the small, incremental improvements. I really liked the GrooveBox-like initial design, because then it changed and became a bit more brighter.

[10:11] Oh, I see what you mean. The colors.

Yes, the colors, exactly. I really liked those. It was a bit rough, but it was just the right amount of rough, and it was very memorable. And you could see it everywhere, in all the offices, in all the Pivotal offices, because there was like so much stuff that we were building. And there were monitors everywhere, and you could just take a look and see exactly what the problem was. And I think the problem was like that we had too many pipelines. So I think that’s where the view came from, right? The one with –

Yeah, the dashboard.

Yeah, exactly.

It’s funny how it all evolved, because initially, Concourse was literally – you would start the ATC program, ATC being like the coordinator, web UI, everything, kind of a bit of a monolith… And you would literally just give it a config file. And that config file was the pipeline. And then we went from there to “What if you want multiple pipelines?” And then from there, “What if you’re on multiple teams?” and then pipeline groups, and now you have like the whole dashboard, like multiple teams, entire enterprises putting everything on one box, and that’s how you lead to melting machines, and things like that. But it started off quaint and fun.

What was the biggest early on challenge when you started Concourse? Do you remember?

I think probably the biggest challenge was just managing the pace of onboarding and trying to balance having a good ratio of people that actually want to use it, versus people that felt like there was some, you know, thing that they have to use it. Because that really changes the types of interactions that you get with people. Like, if you’re trying to – if you’re providing something where you’re solving a problem that they have, you’ll get like much nicer interactions, but if you’re building something that they feel like they have to use, then they don’t pull as many punches. It’s not going well.

Did people feel instinctively, like did they know instinctively what to do with Concourse? Or did it take a while to explain what it is, and how to configure it, and how to – how do you find that?

I think people did pretty okay at picking up how to use it, at least within Pivotal. I’m not gonna go as far as to say it was easy. They probably really stumbled for a while, and I wouldn’t be surprised if a lot of them didn’t like it, because the documentation was just, you know, us writing the best we could; it was all just like reference material. We never really had a technical writer. Yeah, there were a lot of times where I’d be like called over to help someone figure out how to do something in a pipeline… One of the most common pain points was someone wanted to acquire an environment, and then use that environment through a few jobs, and then release it in a later job. And that was always painful to do with Concourse. I think we never really had a great solution to that. We had like an interesting one that used a Git repo as a lock, which worked, but it was a little cludgy, because you had to manually release it now and then. There were a lot of people doing that, because there were a lot of people using Concourse for continuous delivery.

I’m pretty sure that you are one of the people that felt that Concourse was more than a CI/CD system. It was like integrating with all these things. and there was so much possibility… As you mentioned, integrating with Git, with GitHub, with the Git repository for locks and S3… And it was basically, the state - you had to keep it outside of Concourse. There were like some very good, strong principles. How did you think of Concourse from the beginning all the way until like you stopped working on it?

I always kind of thought of it as a way to codify your entire dependency chain and automation process. Kind of like if this, then that, but more generally, what are all the things that people would be manually doing within your organization, or imagining you’re like one person trying to drive an entire startup. That’s kind of where I imagine Concourse being very useful, because then you just can empower yourself to get more done, because you just have something else doing it all for you, whether that’s like automated testing, or automated, periodic longevity tests that run every hour, and just make sure your tests didn’t suddenly get more flaky… Or like testing infrastructure reliability, or just anything that you need to do continuously, Concourse was your guy. That was the idea.

[14:19] I always saw it as automation with a nice UI. I mean, that’s what it was. And you were able to do things - as you mentioned, checks… And at a glance, you could see, are they passing or are they failing? And what is the failure ratio? There were so many interesting things there. The logs… The pipeline view was so important, like the state of resources, for example… It had some very simple primitives, but it was very versatile. It was so much more than a CI/CD system. I think that’s what people saw in it. At some point I know it was like the distribution mechanism for the Pivotal software, because pretty much everyone that was running all these large clusters, whether it was Cloud Foundry, where it was like all the stateful services - how do you keep everything up to date, nevermind the applications? So you needed to provide automation that shows you the health, at a glance, of what is happening. You had to have notifications, all that thing. And also, when there’s a problem, you had to go and debug it quickly.

Yeah, it kind of acted as like the central plane; it was like the source of truth for what’s the status of the whole system… Which is kind of interesting, because when COVID hit and everyone started working from home, suddenly we didn’t have like the central dashboard TV that everyone looked at. It became much harder to keep tabs on CI/CD and metrics and things like that. So that got me thinking more about notifications, or something that like keeps it more in your face, but… I don’t have anything deep there.

What was it like to work on Concourse for so many years? It was six, seven, roughly? It was a long ride.

Yeah.

What was it like?

It was a lot of fun. The team obviously, you know, changed in cycles. Pivotal was all about rotating people semi-frequently. That really slowed down when I moved to Toronto; the rate of rotation really slowed down. I think it was just a different office culture, but… Throughout those six years, it was just a lot of really fun engineers to work with. We had some good team culture things early on, we had every retro - someone from the team would like make a dish from their home culture, and bring it, and we’d like let the whole office have it. I think probably the highlight of my career though was when we had a retro and someone literally just put “I love my job” in the happy column. I was like “Cool. Doing something right, I guess.”

That’s amazing. That was a very fortunate person. It was a very fortunate team. And I think we felt it as users. I mean, sure, we were frustrated at times, but we could see how hard everyone was working… Seeing on GitHub all the pull requests, all the issues, all the stuff that was going through… There was so much stuff; so many good things, great things. And even from the outside, it felt like it was a great ride. So after Concourse, you started something else. Bass. What is Bass?

Bass is kind of trying to learn from what I think were some of the mistakes with Concourse, one of them being try to express a system that can do everything, but within the confines of a declarative YAML config.

YAML is the problem. Everyone listening, it’s not the declarative part. That’s okay. That’s good. We like that. So what is wrong – what is wrong with YAML? What is wrong with that combination?

I think there’s – I could debate both parts, I think. Some aspects of declarative are also kind of falling out of favor with me, but it’s largely – I think it’s because I’m kind of shifting away from both at the same time, so I’m really considering alternatives to declarative systems, too/

Really? Do tell. That’s very interesting.

[17:56] But yeah, with the YAML part, it’s really just like not having a real language at your disposal. You’re kind of inventing like a language within it. We like to say that Concourse pipelines were a declarative schema, but really, it was declaring a set of jobs that then had like an imperative plan within them, and the more bespoke we made that DSL, we got into things like scoping, like what’s the scope of this value that’s being bound within the build plan… Largely with the across step is where this came up. The across step is one of the most recently introduced ones, where it’s like, across all these values, do this step. So you end up like wanting to bind an asset to a value, but then it’s like, does that binding escape to later steps? And then it’s like, why are we just not implementing a language where like doing across is just a for loop? So that’s kind of where I am with YAML. It’s just not very well suited, I think, to actually expressing something… And that’s why so many people end up templating it, and then you just have like two problems. Now you’re like thinking at like a template level, and a YAML level… Now you need to manage that pipeline feeding into the system… So yeah, it just makes things way more complicated, I think.

Okay. So when it comes to the declarative part - I’m still stuck on that, because I wasn’t expecting it, to be honest… And I’m surprised, and I’m just curious - what could be better than declarative?

There’s a solid chance that I’m wrong in this, and I go back to being declarative is great… But the problem that I see with it –

All great engineers say that. All great engineers. “There’s a good chance I’m wrong with this… But still, this is what I think.” [laughs]

I appreciate it. The problem I see with declarative approaches to CI/CD is the system they’re building around is not declarative… The system being developers just running commands. Most people - they’ll go to CI/CD, they’ll know what commands they want to run… Like, “I want to run go test”, “I want to run RSpec”, or whatever their build process is. Commands are already the foundation that we’re really building everything upon. Even Docker and BuildKit kind of like build on that abstraction, because they’re all about just running commands in containers.

The problem I see with declarative wrapping systems for that is that someone has to implement the mapping between declaring what you want, and having that boil down to commands. And we saw this with Concourse, where the Git resource started off as just like a perfect example of just a tiny little Concourse resource. It does like git clone, git fetch, git push… And that’s it. But the reality was that everyone uses Git differently. So if you look at /ops, /resource, /inscript it’s like a 100-line Bash file handling a bunch of different use cases; tagged versioning, things like that. And you have to kind of distill that up to what in concourse is YAML. Resource doesn’t care it’s just JSON. But in any case, somewhere there’s like a declarative config that maps to commands running… And it just like kind of adds an extra level of indirection between what the developer knows they want to run, and how they know it’s actually going to run. And there’s like the added toil of someone managing that mapping interface.

All that being said, commands aren’t necessarily the best interface to expose. It’s just what people already know. I think if you are able to express something as just a declarative thing, and it works, and it’s like low enough maintenance… And maybe you get bells and whistles like static typing, or easy to verify schemas, and things like that - then I think it is possible for the value trade-off to be there. But I guess, from my current perspective of trying to build Bass as like a side thing, not expend too much effort, it would be a lot of effort for me to have to invent these mappings for everything, as opposed to just being like “Hey, it runs commands.” So maybe that’s my bias right now.

[21:57] Yeah. So when you say commands, are you thinking more like – rather than having this mapping between a declarative thing and a command, you’re thinking just in terms of commands? So when I hear that, I’m thinking about the functional paradigm, where you have a function, there’s an input and an output, and then the focus is on the function, not on the mappings. Are you thinking along the same lines, or is there something else?

Kind of. I mean, a lot of commands really are just you’re running a function, and you’re expecting some output. I’d venture like 99% of the time that output is either like a file on disk, or something that it wrote to STDOUT, maybe a JSON stream, or something like that. So you don’t really control whether the commands are idempotent, or like pure, or anything, like in a functional sense, but they do very much feel like a functional interface.

And there are exceptions there, where some CLIs have like sub-commands, and different syntax for it, but it ultimately boils down to like you’re identifying a function call, passing it parameters, and it’s giving you outputs. So yeah, I guess I do kind of see command lines as a very functional interface, and being able to pass results from those commands to another - I think that’s really where the special sauce is from Bass. Because if you try to just script things running commands in Bash, you have to deal with those files; you have to put them somewhere, pass them to this other thing, clean them up after… So I’m trying to build something that makes – I guess something that treats commands like functions that you can easily use.

Some team members had this joke on the RabbitMQ team, which - RabbitMQ uses Erlang, which is a highly, highly functional language… And the joke was that if you’re an experienced enough programmer, you’re most likely a functional programmer. Like, basically it all boils down to a function somewhere. And once you come to accept that, your world will be better. Obviously, that’s not always true. We had Gary Bernhardt a few episodes back, and if you haven’t heard his Faux-O talk, you should, because it’s a very good one. He explains why functional is just weird, and why object-oriented has its own shortcomings… But Faux-O is a thing, and I really like it. Anyways, we can put the link in the show notes.

So I’m wondering – because the Bass language, bass-lang… Dot com is it?

Org.

Org. Thank you. Dot org.

I might own .com, but .org is the canonical…

So bass.lang.org, it explains – by the way, it’s a very nice website. The GrooveBox theme… I love it.

It’s actually different.

Okay.

It’s different every time you load the page.

Really?

There’s like a handful of themes that it shuffles through. There’s a kind of a callback to Concourse, because at one point we were thinking of switching the color scheme, so we added a – if you press like a special key, maybe it was like Alt+S or something, it would actually bring up a little dropdown, so you could change the theme. So I brought that back to Bass, but a little more extreme, because it literally changes every time you load the page. But you can change it if you want, at the bottom.

Really? I don’t think it changed. Mine has stayed the same ever since…

Scroll all the way down… Do you have a reset button there?

Reset? I do have a reset button.

You probably pinned it to a theme at some point.

Ah, so I picked it. See, I picked it. Alright. Let me reset that. Okay. Oh, I see it now. Okay, now when I reload, I see it. Yeah, okay. So I chose GrooveBox. Okay. Alright, that’s really cool. So every page is different, like differently colored, every page load. That’s really neat. Okay, very nice.

My favorite is rose pine. Shout-out to rose pine, I guess.

Rose pine. Let’s check it out. Hang on.

It’s a very nice, like luxurious looking-color scheme.

Rose pine… Dawn? Moon? Or the classic.

Just regular.

Regular rose pine.

Oh, they’re all good too, but Dawn is the light mode.

[25:52] Oh, I see. Interesting. Rose pine Dawn. Okay. Yeah, go check it out. Ah, yes, rose pine – that’s like the dawn, that’s like the light one, and the moon is the dark one. Very nice. Okay. So you have all these concepts, you have like the bassics… And I love that; it’s not a typo. There are double s’es. The bassics. Is the thunk – I’m looking for a thunk. Is that what would the function equivalent be in Bass?

Thunks are named that way because they kind of mirror zero arity function calls. But they represent commands. So that’s the distinction. Bass is a functional language, but it represents commands as like a lazily-evaluated data structure called a thunk. And it’s also just called thunk, because it sounds funny and semi-musical.

Yeah. Okay. Where does the Space Invaders thing come from? Because that’s another thing which I noticed. That’s a good one.

That’s a good question. Honestly, I don’t know why I picked Space Invaders. I wanted something – there’s a pattern in the docs where sometimes it’ll show a thunk, and then show it again in another context, so I wanted it to be easy to recognize that they’re actually the same. So it was either like Gravatar, or build like a Space Invaders thing, and I thought the Space Invaders would be more fun… Because I wanted a way to tie the colors to the color scheme too, so that way I can control the whole stack.

That makes sense. I’m just looking at the image now, and I can see the three echoes which have a Space Invader that looks the same… And it just shows it’s actually the same command, right? That’s what that’s representing.

Yeah. And if you click it, it’ll show the actual attributes of the command.

Oh, wow. That’s amazing. You have to check it out. As a listener, it’s okay to put on pause and to go and check bass-lang.org, because this is a really nice website. I can’t believe that you do this for fun in your free time. Like, you must really love CI/CD, the whole functional paradigm, and this problem space. Why is that? Why do you like it so much?

I think it’s more broad than CI/CD. I just like the whole process, I think, from building and publishing software. There’s another side project which I’ve been like putting out there, but really no one cares, because it’s just yet another static site engine… But this site is built in Booklet, which also has its own – I think it’s like booklet.page… And you can really tell I built both of them, because they look the same.

Yes, I can see it. Okay, I can see the same structure. That’s really cool. So I can see a lot of like a Lisp-like structure here, and Lisp-like structures…

That’s true, too. In Booklet, you mean?

Yeah. Why Lisp?

I think the fundamental appeal of Lisp to me is being able to do a lot with a little. Maybe that’s even the part of the appeal of Go to me, too… Because Go is – it’s a pretty small language. It also is kind of in that mindset. I’ll probably offend a lot of people saying like Lisp and Go are similar to each other… But I think fundamentally it’s the same thing that attracts me to both. But especially Lisp, because… Like, a long time ago, before I actually got into professional software engineering, I was just learning a lot of languages. I’ve always just really been into languages. And I especially liked ones where it’s like you start with these five primitives, and from there on, you can build anything out there. It’s like Turing-complete. So that’s what brought me to like Scheme… Racket was also a lot of fun, because it was all about building languages on top of Racket and I think the world needs a lot more of these like tiny, domain-specific languages that try to focus on one thing, and Racket tried to be the platform for building those languages.

But there’s actually kind of an interesting story behind the specific flavor of Lisp that’s behind Bass… It’s actually based on kind of lesser-known one called Kernel. Kernel’s whole thing was, you know, Scheme was six abstractions, Kernel was five, because it took one and made it more generic.

[29:59] So you know how lisps - they’re known for having macros, right? Like, compile-time macro expansion. Kernel, instead of having macros, it had something called an operative, which is something that deferred the evaluation of its arguments. So when you called an operative, you would get the unevaluated forms and the colors scope, and then you could selectively evaluate them in the colors scope. I think IO actually is kind of similar to this.

So yeah, a long time ago, I tried implementing that. I implemented one in Haskell. It’s called Hummus. I implemented one in RPython called Pumis, and one in my own language, called Cletus. Guess which one was the fastest?

Your own language? No way. Your own language is the fastest one. [laughs]

No, definitely not.

No? [laughs] Wrong answers only.

It was Python, actually. Because it was specifically RPython. So PyPy would compile it to C, and then it just like blew the other implementations out of the water. So I did these a long time ago, probably like 2010… And then right about the time I was leaving VMware and looking to start on Bass, someone actually approached me and said, “Hey, we’re trying to collect all the implementations or details for Kernel, because the guy that invented it just passed away.”

Wow…

I was like “Damn, I’d never talked to this guy.” Now I feel kind of bad, because I feel like I kind of carried the torch a bit with Bass, but there’s nothing I can do to make him aware of that… But yeah, he was a really cool dude. John Schott. I’m just saying, really cool… I don’t know him. He was probably really cool. He apparently contributed to Wiki News a lot.

Okay. Well, if anyone knows John Schott, or anyone knows – like, this is a shout-out to him. And if you know anyone that worked with him, that’s amazing. Yeah, just let them know that the memory and his ideas live on in Bass. Wow. That’s a great story.

Very interesting, but the trouble with Kernel is it’s hard to optimize, because there’s literally an eval after every corner. But that doesn’t matter in a language like Bass, because the bottleneck is going to be running containers; the runtime interpreter is probably not going to be slower than that.

One of the Bass components is this, as you mentioned, the runtime compiler. Is that what you’ve said? Runtime…

Well, there’s runtimes. There’s no compiler.

Oh, right. Sorry. Okay. How do you call, basically, the language in which you code Bass? What is that component? So there’s the runtime, which actually runs it… And this is the frontend of it? I’m just trying to find a name for it that describes it, what it is.

The interpreter of the language itself?

1:The interpreter, yes. Yes, the interpreter. Okay. What is the runtime of Bass?

So it gets just parsed into a syntax tree of – at that point, it’s just forms. You know, as with Lisp, there’s no difference between like a form and a value. It’s just whether it’s been evaluated or not. So that gets fed into Go, it walks over each of the forms and calls eval on them.

[34:16] The tricky thing is everything is implemented in continuation passing style, which is a way of implementing tail recursion, essentially. So languages that are implemented on like a non-tail call optimizing platform usually do that, because otherwise there’s no way to do infinite loops… Which would be bad for a continuous system, because its point is to be an infinite loop. So if I didn’t have continuation passing style, then probably eventually Bass servers would die, if anyone was using it for CI/CD.

Yeah, that’s a good one. I’m pretty sure that Erlang is optimized for that, because it just like – it has to be able to deal with like infinite loops. And yeah, it’s optim– okay, okay. So yeah, that makes sense. The list comprehensions, and all that - it can just keep recursing, and you won’t blow any memory or any stack or anything like that. Okay.

So where does all this code run? Where do all those instructions run? And I’m trying to get to the BuildKit part, because I know looking at Bass that that’s the runtime, but where does that run? How does the interfacing happen, and how does something useful get produced in Bass, as a container, or a file, or whatever the case may be? A binary…

Well, the language runs in the same way that like Ruby or Python or any other interpreted language does. So that’s one huge difference, actually, in case hasn’t been made clear yet. I guess it’s like between Concourse and Bass. Concourse is like a service that you deploy, and you’ve pointed to a database, and it maintains all this state, and you feed it YAML, and like YAML is like the language that you’re writing. Bass - there’s no server, it’s just a language interpreter. So you just run Bass files. If you want to run a CI/CD server, you’re just running a Bass file that’s a loop. So that’s the key difference.

But when it comes to BuildKit, that’s where it actually just talks to BuildKit over the regular gRPC interface that it exposes. So that could be local or remote. I think I’ve only really tested it locally, but in principle, it’s just like calling over the API. And I think the client already handles like uploading files, so I think it would work remotely… But I haven’t tried yet.

Yeah. I also know there’s like the Bass loop component. What is the Bass loop?

So Bass itself isn’t really a CI thing any more than like Ruby or Python is, so Bass loop is basically the CI thing. I had been just running Bass in GitHub Actions, but it was just very slow, because you don’t control the environment. I’m developing Bass on like an RX 4950. I’ve probably butchered the name, but whatever the really nice AMD CPU is… But then it’s like running on some collocated server, probably in GitHub Actions. It’s not able to use BuildKit efficiently, because it’s a new run every time; you could use caching, but then you’re trading like CPU time for just IO time, managing the caches.

So what I wanted to do with Bass loop is have a server that I just run, that receives GitHub WebHooks, and then you bring a runner to it, so it doesn’t have its own dedicated CI stack… And it’s basically WebHooks come in, and it evaluates Bass code in response, by like calling out to your repo.

And where does the runner run? And what is the runner, in this case?

The runner is someone running bass–runner, and then github.bass-lang.org. What that essentially does is – if anyone’s familiar with how Concourse Workers ran, it’s very similar, where Concourse had like an SSH gateway called the TSA. You’d connect to it, it would forward some connections, and then when the ATC needed to use that worker, it would actually talk to a local forwarded address through SSH. The runner is doing basically the same thing, where it exposes the local runtimes as a gRPC service, so then when a WebHook comes into Bass loop, it connects to the forwarded address and then uses that runner. So that way, I can actually use my AMD massive developer machine, instead of being, you know, stuck with whatever the free tier is on GitHub Actions.

[38:26] Interesting. What about registering your own GitHub runner? Have you considered that?

I don’t know what those words mean.

Okay. So you know, you get like the free GitHub runner, just by default, but then you can run your own… And you can either have like a VM-like process, that registers with GitHub, and then the runner is available to pick up jobs…

Gotcha.

Or - and I’ve seen this as being more recommended, because of the ephemeral state of GitHub runners; they are supposed to be cleaned, and brand new on every single run… You can run a controller in Kubernetes, and then the runners are like registered on-demand based on what jobs are available. That scales a bit nicer, and you get containers… But again, you should be able to trust your infrastructure, or… I mean, it’s a tough problem. Running this is a tough problem, and that’s why the majority will just use the free tiers.

Well, it sounds pretty similar. It sounds like something I could do. But I guess the other goal which I didn’t mention is escaping YAML.

Yes, that’s a good one. That’s a worthy goal.

If I’m using GitHub Actions, then I’m back to YAML.

Oh, yes.

Back to those wrappers managed by, you know, random people, doing their best, but still, just a lot of dependencies to manage.

Don’t you miss the GitHub Marketplace with all the actions that you could use from there?

Not really, because like most things that I use, including GitHub itself, they already ship a CLI. So to ship Bass, for example, I just run gh release create, or whatever, but as a Bass thunk.

Yeah, that kind of gets back to what I was talking about, with all the declarative wrappers - if you avoid that and have your abstraction level be lower, then you automatically get like the entire marketplace, which is being built by everyone.

Yeah. So you do have this file, which made me smile when I’ve noticed it. It is a Bass file, and it’s called the “ship it” file.

Yeah.

What does the “ship it” file do? [laughs]

It ships it. So the gist of it is it builds a binary for each supported platform… So Linux, Darwin, Windows, Arm for Darwin as well… And then it just passes that to gh release create, which - all those words I said about declarative wrappers, I actually wrote a wrapper myself for gh, so… Maybe it’s just that I like functional wrappers more than declarative ones… But yeah, it’s just a small script that takes the – it reuses the functions for building Bass and just passes the result into the gh release create command. But the nifty thing it also does is it takes the data representation of those thunks, like the JSON format, and publishes those to the release as well, and then it publishes the SHA-256 of each file.

So kind of the neat thing that I want to be able to do with Bass is like not only have it so you can build up those thunks and have them get like bigger and bigger and bigger as you pass more results between them, but you can actually just snapshot them… And assuming those things are hermetic, then you have a reproducible build that you can publish.

Interesting. So you say hermetic meaning something that’s is the same…? Something that’s like idempotent?

It accounts for every input that might change its result, is kind of how I sum it up. So if you have like a hermetic data structure and you run it like today, and you run it tomorrow - assuming the inputs are still available, granted, but the point is, yeah, you should get the same result, no matter where you run it… Which is kind of a fundamental building block, I think, for CI/CD. It was something Concourse tried to enforce, but I think that’s also where a lot of people ran into pain with it, was Concourse being a little too overbearing.

[42:21] No, I think that’s really important, especially like supply chain security is more and more in our minds… And for that, you need to have this property; without this property, it’s very difficult to achieve that. You should be able to build the same thing, compare it bit for bit, and make sure, again, given these inputs, this is the output. And if you can trust the inputs, and you can verify the inputs, and you can, again, access the same inputs, the output should be identical. And if he’s not identical, you have a problem somewhere.

And you also have to trust the thing that’s building it, I guess, but…

Yes, for sure. But the thing that’s building it, I suppose it can be the same – like, if the same builder runs in multiple locations, and it uses the same inputs, so it doesn’t matter where the builder runs, the output should be the same. Right? Because there’s no state that the builder has, not even time, that makes it – you know, like if you have time drift, like milliseconds, microseconds, anything like that, it will not have any impact on the final artifact. And that’s super-important, because then you can compare two things; you know, run remotely, and even completely different architectures, but the end result should be always the same. It’s a nice way of verifying it, I suppose, as well.

It’s funny you mentioned time, because that was one of the things that broke the initial builds of Bass, was that when you archive something up, it has timestamps in it, right?

Yup.

So if you tried to download those JSON files and rebuild Bass back in the day, it wouldn’t produce the same thing, because the archive had different timestamps in it. So now what Bass does is it actually normalizes all the timestamps. So when you a thunk build something and then you pass that result to another thunk, it’ll actually see the timestamps as 1985, some specific date…

Okay… It’s not your birthday, is it?

No.

Good. [laughs]

I stole this from the Node community, I think… It’s the exact timestamp from Back to the Future, and I figured I might as well make it a standard, because either one’s going to be arbitrary.

That’s an amazing reference. Okay, so that’s part of Bass, too. Space Invaders, Back to the Future… What else is part of Bass? This sounds like a very interesting project. [laughs]

So actually, I was prepared to ship the next version of Bass on Ship It, but I’m terrified of running this command on my machine while doing a screencast, because I’m using my partner’s old MacBook… But it has a very important feature, which I call the Rave mode, where if you press R, there’s a little spinner where it says playing… Actually, I can link you to the pull request that adds it, because it has a pretty good GIF.

Yes, please. This sounds amazing. No way, so hang on - you’re trying to ship a new version of Bass on Ship It? Is that what’s happening right now?

That was the plan.

No way… No way…! And by the way, dear listeners, it’s Friday, 7pm as we are recording this… So what could possibly go wrong?

It’s 2 PM here, it’s fine.

Oh, yes, it’s 2 PM for you, so it’s fine. It’s only for me 7pm. [laughs] That’s amazing. Okay…

I put a link in the chat, if you want to see… There’s a GIF there.

Yes. Yes. Yes. Thank you. Pull request 222. No way… We are not making this stuff up. Is the 22nd of July as we are recording this, 2022, and the pull request is 222. No way. No way. This is too good. [laughs] So I’m looking at the rave… I love that little bar. Is that it? Like the little shrinking bar?

Yeah.

Oh, wow…! No way…

[46:09] So this was actually quite an adventure. It took like four days to implement this thing. And this is four days of vacation, not just like four days after hours… Because it syncs with the Spotify API. So like each beat that you’re seeing there is not only synced to like BPM, it’s actually literally rendering the beats in the song.

No way, man. No way.

So if you try to play – if you listen to like Lateralus by Tool which has like changing time – I forget what it’s called. But it’ll actually like speed up and slow down to certain parts.

Okay, this is too cool. This is too cool. So how can I try this? How can I test this?

You can install from Main, like from source.

Okay. Alright.

But it integrates with Spotify. So I don’t know if you use Spotify.

This recording just got derailed… [laughs] So I don’t know whether we’re in meta mode, I don’t know what’s happening anymore, but I know it’s really cool and I want to try it out right now.

You can probably just go install it, actually. I don’t think you need anything like that. If you brew install Upx…

Brew install Upx…;

Yeah, that’s one gotcha, a dependency that you’ll need…

Upx, okay.

That’s for compressing the binaries. So like Bass has to – when it calls into BuildKit, it has to run thunks like through a little shim to like meet the interfaces that it needs, like supporting STDIN, for example. But those binaries are too large to pass over gRPC, so I have to compress them and then bundle them, and that’s what Upx is for.

Interesting. Okay, so I have Git, I have Go, I have Upx. Okay. Git clone, cd in, make install

Yup. That should do it.

Okay, cool. Man, this is really cool. I was not expecting this, but I’m loving it.

Do you use Spotify?

I really, really do. Um, no. But I can get an account…

Okay…

No, seriously, I’m getting an account for this. This is like worth it. This just got derailed, but it’s amazing. Sign up… Let’s see. Sign up with Google… Yes, yes, yes…

Oh. There you go.

Oh, this email is already connected to an account, so I must have one. Okay, continue with Google, and I don’t even know one. “You don’t have a Spotify Connect to your Google account.” Okay. I have a username. And it works. Okay, I’m logged in. I do have Spotify, and I didn’t even know. That’s how long ago it’s been. Okay. So I have Bass, okay, and let me just install it. ..Okay, off it goes. “You’ll need BuildKit running somewhere, somehow.” Okay, I have –

If you have Docker running, it should just start it for you now.

Nice. Yes, I do, actually.

I need to update the – I need to push the docs.

Yeah, cool.

I stole that from Dagger.

Very sweet. That’s amazing. Okay, great ideas. Great idea. See, that’s what happens. Okay, what is Lima?

Lima is a really cool project where they’re trying to – you know, there’s like this general pattern of a lot of developers use Macs, but they need to use Docker or like some other Linux tool. Lima is basically generalizing that, where instead of having like a VM managed by like Docker Desktop, and another VM if BuildKit productized itself… Lima is like a general template toolkit for spinning up VMs with software pre-installed. And they had one for BuildKit. But you shouldn’t need it anymore, because now it’ll just spin up BuildKit in Docker.

Interesting. Okay. I have Bass!

Oh, it works?

What do I do next? Bass Rave?

Bass… You could run a demo; like booklettest.bass. Demo’s booklet test.

Okay, so [unintelligible 00:49:46.17]

Yup. Test.bass.

Test.bass. Yes.

Okay, now press R…

R. Yup. Okay.

[50:01] That should open a browser.

It did, but you don’t see it, because that’s like on a separate one… Okay, yes.

Yeah. So now it should be synced. If you press D…

D in here?

Yeah. Like in Bass.

Yes.

Oh, it doesn’t look like it synced, actually. Let’s see – maybe because you don’t see the other window, maybe there’s something wrong and you don’t know what is wrong. So let me stop sharing this window and maybe share – you know what, let me try showing the entire screen, how about that? I’ll share this entire screen. I’m going to move this on the left-hand side and I’m going to move this on the right-hand side. So that was Spotify… That’s what I want to do. So Bass, this one - press D, you said? Oh, there, it currently couldn’t decode…

User not registered in the development dashboard… Do I have to enable users? I’ve never – like, I’m the only user right now, so…

That’s great. We’re testing this. I love it. You haven’t shipped it yet, right? Like, we are still working towards – like, basically QA-ing the feature that you’re about to ship, and I’m the second ever user to do this.

That’s right.

So I think this is exactly what we would expect to happen. It works on your computer… But does it work on mine? That’s the question we should try to answer now.

How to enable – oh, it’s because it’s in development mode. Okay. Can you put your Spotify email? I think if I just add you here, it might work.

Yes, yes, yes. It’s this one.

Good to now.

And this is the Spotify username. Same as my Twitter, @gerhardlazu.

Okay, try now. You probably also need to be playing something.

Okay. Let me play this.

If you want, you can run one that’s like infinite. If you don’t mind spending one of your cores, you could run demos/fib-loop.

I have 10. Not a problem. Even 20. But anyways. So demos/fib-loop?

Yeah. With a dash.

Off it goes. Okay.

And then try pressing R.

R. Yes. Nothing happens.

It didn’t show that error now, at least…

No, it didn’t. Maybe it’s already connected.

Try capital R to clear it, and then r again to…

Yes. It opened this.

Okay.

Agree?

Yup. That looks fine. And you’re playing something?

I’m not playing anything just yet, but I’m playing something now.

Okay. And then - yeah, press R again to sync it.

R again.

There you go!

Nice! Oh, look at that!

If you press D, it’ll show the –

D.

Yeah, there you go.

Yes! Oh, no way… We made a thing change color… [laughs]

How many engineers does it take…?

…actually be synced to a song that I’m playing in Spotify… Oh, this is so cool. [laughs] No way…

The tragic thing though is Spotify’s API doesn’t give you enough info to actually sync it perfectly. So it does its best, but if it’s out of sync, you can press minus and plus to adjust the timing.

Okay. So if I do minus now… What does minus do?

It has it go back by like 100 milliseconds.

Okay.

So it’s just like a slight timing, because often it’s out of sync.

No way… So let me try and summarize what we’ve done here… We are running an infinite command in Bass. We have synced the Bass CLI – we’ve connected the Bass CLI, we’ve authenticated the Bass CLI with my Spotify account, and whenever I’m playing a song, whatever is running in Bass locally, it synchronizes with a song, and the BPMs and the colors match what is happening in the song. Is that what we’ve done here?

It doesn’t affect like the program, or anything. It’s just purely that little spinner thing there. But yeah…

No way…

Usually, when I’m working on something, I’m listening to music at the same time, so it’s just kind of fun to see like a spinner sync up to it.

[53:58] This is amazing! I have to take a screenshot of all this. I’m going to move some windows around for us to see this. I’m going to stop sharing my screen, so that I can take a proper screenshot. I’m going to adjust some lighting, and this one is going in the show notes. All this. Because this is unbelievable. Alright… This is the screenshot that will make it in the show notes. Not the one that we’ve taken early on; this one, that shows this amazingness that we’ve just done.

Okay. So step one is done. Step two - shipping it, right? Because we confirmed it works.

Right. Well… Ish…

Anything else that needs to happen?

It works as long as I’m acutely aware of everyone that uses Bass and add them as a user of this app. So I need to figure out how to change this app to a different status.

So he’s not a developer anymore. That’s the one. Yeah. Well, I have to tell you, I feel very special for being the first user other than you for which Bass works in this way. I’m super-excited about this.

I appreciate the testing.

Anytime.

So do you want to ship it or not today?

I can tr– so last time I tried to ship it is when I like disconnected and everything went wrong, because I switched monitors, and then this is connected through USB to that, and just like everything crashed.

I see.

I will try though… I’ll try to do it just on this machine… And it’ll take a while. because it has to like build the world.

By the way, it’s using more than one core… Okay, I don’t see it anymore, because I’m not sharing my screen… But let me do this… Let me share this window. And if I do hstop. If I sort by, process no I don’t want a tree view. There we go. Actually, you’re right; it’s 132%, so it’s not quite that much.

The rest is probably just re-rendering the UI, because of the spinner.

The re-rendering the UI… You mean this one? This one right here?

Yeah.

Okay.

There’s a lot of magical shell escape sequences going on to render that…

This is amazing. Wow… We had like something similar with TTY2 and TTY on Dagger happening just like this week, and… Oh, wow. Some people will have some questions for you. How did you accomplish this magical feat? And guess what - Bass is open source, so anyone can go and check it out, including you, dear listener. Have a look at Bass… Vito/Bass on GitHub?

Yup.

I’ll put the link in the show notes. Okay.

Please refactor my code for me. Someone’s got to do it.

Yes, exactly. Yes. Pull requests, please. That’s how all great software is built these days. Okay, cool.

[01:00:03.08] I can start shipping it over here… Maybe I can try to share as well.

Go for it, yes. I’m going to stop sharing my screen, so you can start sharing yours. I’m going to Ctrl+C my fib loop, Ctrl C… Yes… Man, this is too cool. I was not expecting this, but… I’m delighted, I have to say. Mission accomplished.

Yeah. So this is shipping Bass 0.9. It’s gonna take a long time, because it has to build the Nix image for shipping Bass, which has a bunch of dependencies… Not a thing that’s even started yet. Yeah, it’s showing the music visualization there… There’s no way to tell, but I’m sure it’s out of sync.

Yeah, this visualizer, the colors on the website, the Space Invaders, the little Bass cleffs that show up next to paragraphs to give you a deep link - these are really all efforts to keep Bass fun for me as a maintainer, and also make it obvious that this is a tool built for fun… And if you want to have fun, come hang out and contribute.

Because I think that was one of the things that went kind of wrong with Concourse, was it was – no matter how much we tried to inject fun into it, really the user base was like serious business; people trying to do like very serious things, like ship software, run CI for their organization.

One of the most controversial things I think in Concourse was if you run Fly and Concourse isn’t running, it says “Is your Concourse running? Better go catch it, LOL”, which we got some complaints about, because it’s like, when my server is not running, I don’t want to see you making fun of me… Which is fair, but…

Hm… People taking themselves too seriously. You know, I do that sometimes. I do that often, actually. And I think we all do, to some extent. I think taking ourselves first and foremost too seriously - you may be stressed, and that’s just like a sign that you’re stressed, and some of the checks and balances aren’t working quite as well as they should… And you stop seeing the fund in things. This stuff is supposed to be fun. We’re supposed to be enjoying this, because we spend so much time dealing with all sorts of weird stuff. Mistakes. Mistakes which well-intentioned people did the best they could with what they knew at the time… And that’s it. That’s all. No one tried to introduce the bug; no one tried to ship the broken software. A number of things just went the way they do, as they do, and that’s what you end up with. How are we going to improve it? How are we going to, you know, take it lightly, do the best we can, improve, and remember to keep having fun. So I really like that story. I really like how you’re thinking about this. I think more of us need to do that.

Yeah. I think there’s nothing more humbling than trying to build software, especially if you’re trying to build software for other people. It’s easy to build software for yourself. That’s mostly what I’ve been doing with Bass. And I think that’s a good thing. It’s harder to build it for other people, because you don’t know exactly where they’re coming from. That I think is one of the things I kind of feel bad about with Concourse, was it was very strongly opinionated, and over time, a lot of users came to Concourse not because they chose it and bought into those opinions, but because the organization chose it, and then they had to deal with the very strong opinions that Concourse had about things. For example, passing runtime data into tasks is like a hill that I died on in Concourse, because I didn’t want it to be possible to have your tasks become not hermetic and become dependent on Concourse itself… But there are reasons people end up wanting that, because they’ve already bought into Concourse, and having that become a blocker means having to buy out from it, and completely switch to something else, which if you like the rest of it, it’s not great to be blocked on that.

[01:04:00.22] So that’s kind of another thing I’m doing differently with Bass, is trying to meet people where they are more, and make the good patterns feel obvious, make the bad patterns not feel great, but probably still be doable, to some extent.

Still okay, but yeah, not the best experience, for sure. I think a lot of frameworks, the ones that stood the test of time, are a bit like that. Things are possible within them, but then you’ll feel the pain, because you’re trying to go against what they were designed to do. And I think it’s almost like you need to know when you’re off the well-trodden path, or when you’re off – not what is possible, but what is easy. And some things may be unfinished, but if something is simple, I think, if something is minimal, as you mentioned… You mentioned –

Scheme?

Scheme, thank you. Scheme. Yes, that’s the one that you mentioned. So you went from six to five, because you realize you don’t need the sixth one. Really simple primitives, but that are dependable, that are intuitive to a certain degree, because it’s still, you know, all abstract stuff… And that tends to be hard, especially when you start combining things, and then you can’t imagine all the ways in which you can combine it, what happens next, second order, third order effects, and so on and so forth.

The point being, if the surface is small, if the interfaces are well defined, if there aren’t many combinations possible - because there shouldn’t be that many combinations possible, I think - because you have the number of items, of like items in the set is smaller - then fewer things can go wrong. And if something does go wrong, then you will address that one thing, but you don’t add more features; you don’t add the seventh, eighth, ninth element, so that you start having like this explosion of permutations.

Right. It’s a system, and everything ideally reflects on each other. I think you build a good system by having – every component leverages some other component within it, because that’s also what kind of installs those guardrails, and at least makes it easier to justify, “Hey, this has to be this way, because otherwise this other load-bearing property of Concourse or Bass just doesn’t work.” And you need that because - well, you just want that. Like caching, for example. It was kind of a forcing function for having resources be pure. And you definitely want to be caching all those fetches, right?

How do you handle that, by the way, in Bass, the whole caching aspect? Because that’s a big one, and actually, it’s even like in the tagline. I’m going to read it, because I want to say it exactly as it is. “Bass is a scripting language for running commands and cashing the s**t out of them.” That’s supposed to be funny… But ironic, not arrogant. That’s what you want - you want everything to be cached all the time.

Honestly, all the magic there is in BuildKit. Bass is really just building up the LLB data structure and just sending it over the wire. BuildKit is the one that tracks all the dependencies between things, and if it doesn’t need to run something, because it already ran it, then it just won’t run it. So if I run this ship-it thing - if it ever finishes - if I run this again, theoretically it just doesn’t go up, because every command is cached, and every input is controlled. Where that starts to break down is when you start passing things in from the host machine. That’s where you need really good diffing properties. This one should be fine, because none of this should be coming from the host. It passes the SHA in, and within this JSON file there’s a git clone and a git checkout somewhere of that SHA.

And BuildKit, when it comes to running BuildKits - I know there’s a couple of good talks, including one from Apple, I think it was from KubeCon 2021; I can leave a link in the show notes… And they’re talking about how to run BuildKits in the context of Kubernetes. You have a cluster of BuildKit instances, and then you know where the caches are located. So do you do like some smart routing, so you know where to send jobs… You do some hash-based routing, and then you have most likely things in the cache. But the cache is distributed.

[01:08:00.01] Yeah. It’s tricky, because this is one of the things we struggled with with Concourse, was do you bias to place workloads where a cache is present, or where it’s not present? Because if you do one, then you end up with like everything thundering onto one machine. If you do the other, then you’re not caching as much… Ideally, you’re caching once per worker, so if you run things enough, it’ll warm across the board. But yeah, there’s trickiness within there as well, I guess is alll I would say. Sometimes it comes down to the use case, like the user has to know if it’s going to be cheaper to transfer this over the wire, or just fetch it from scratch. Sometimes it’s faster to just avoid the cache.

It’s like a giant repo.

Interesting. Do you think that it’s important for caching, for it to be as close as possible to the compute? Or do you think it doesn’t really matter if the cache is too close? Because in my mind, I think the cache should be on the same instance where the compute is. So it’s almost like you want to distribute the job using maybe like a hash ring algorithm, so that jobs, the same job ends up on the same host, on the same node.

I know that Cassandra had this, it had like a rebalancing mechanism, where if you added more nodes into the cluster, there’ll be the hash ring, so each node would occupy less of the of the hashing space, and there will be like some rebalancing where the data would move across. And then there would be like one or multiple nodes that would just like basically serve the cache that the new node was supposed to serve? Is that too complicated, do you think? Or do you think it’s necessary? Do you think there’s something simpler? How do you think about that? Because that’s a really interesting problem, especially for CI systems that need to run at scale, and you need to balance the staleness… Like – sorry, some jobs need to be fresh, and other jobs need to have a cache, because they will run faster.

It’s still like the fundamental question, I guess. I feel like it’s impossible to predict really, because it depends on how long does it take to build the cash, versus how long does it take to transfer the cash. I don’t have any unique insight on the Cassandra-specific things you mentioned there, but that’s the fundamental thing with Concourse, and that’s where – at one point, we were considering tracking the average duration, like on a task by task basis, because then you can kind of try to make that calculation. But you have to benchmark it against like the internal network transfer.

So I guess, ideally, you would have a system that can kind of learn from the things that it’s running, which - that gets tricky, because how do you identify these things? It depends on like the hermetic aspect, right? Because if you’re running something that’s completely controlling its inputs, and maybe you could reuse a git clone from earlier, you need some way of identifying that they’re really the same.

Exactly, yes.

One thing I was experimenting with in Bass was having it so that when you do a git clone, it would actually have multiple layers. It would have one initial layer that is like just git clone the repo, cache this every day, and then a later layer does a git fetch, to bring it up to speed, and then the layer after that does a git checkout. That way, you can kind of have fine-grained – you can have coarse-grained caching at the lowest level, so you’re only cloning once a day, but then fetching at some other interval, and then the final checkout is how you get there. So I guess that’s one way to cut it, and have more fine-grained caching, of Git repos specifically.

That’s interesting, yeah.

Yeah, I don’t think I’ve seen a system that really learns from the runtime of how long things take to run, versus the size of the output that comes out of them.

That sounds like a really interesting problem, and I would love to solve that one day, because it sounds like it will unlock so much – like, forget AI, forget machine learning, forget all that stuff. I think it gets just too much hype. Something simple like this, that can keep track of what is happening in the system, and based on what happens, it can try and do something like literally little optimizations… “Okay, based on this, I’m going to try that.” And that result, it’s going to use it for the next calculation. Based on all these things which I’ve done, I think this is going to be better. Just like small iterations towards eventually finding its own sweet spots.

[01:12:16.18] It just reminds me a bit like Conway’s Game of Life. You know, they just keep changing, and eventually, you start seeing those patterns. And it just happens, and they just didn’t know what to do… Like, how is that even possible? They start mimicking, you start seeing – it’s just fascinating.

So that’s one I imagine for this caching problem, where it just learns, and eventually just gets to a point where it’s stable, it’s happy, and there’s nothing more that you can do to improve, and then everything is cached.

Yeah. I mean, I guess it is machine learning.

Yeah, in a certain way…

In the basic, in the most basic sense, right? It’s a machine learning how long things take.

Yeah, you’re right. You’re right. It is. But I think it can go so crazy, right? You have all the different – then you have neural networks, and Bayesian filters… It just goes a bit crazy after that. And most of it is over my head, to be honest, but… I like things simple. And I think simple is defined by my capacity of understanding things, because that’s what it is, and it’s everyone’s capacity… So there’s like a common point where each of us – it’s easy for us, for all of us to understand that quickly and easily, and I think that’s what’s simple for most of us. That’s what I think of it.

I always also prefer simple, because at least when it breaks, you know probably what will happen. One failure mode for that, I guess, is you’re running something on a shared machine that’s also running something else that’s really expensive, so it messes with your numbers, and it suddenly thinks it’s more expensive in the future… But maybe there’s just a button to clear the cache. All everything comes down to is clearing the cache.

That’s right. Cache invalidation, right? Right, okay. So what was the most fun thing to work when it comes to Bass? The thing that you enjoyed working on the most. Because this was important… Making Bass fun was important. What is the most fun thing so far?

I think building the language itself. There has been a lot of different vectors for fun, but just getting back to what I was really into back in the day, just like coming up with a language and trying to have as few concepts as possible that leverage each other in interesting ways… One example is in Bass what you might call maps in Clojure, or like hashes in Ruby, is called scopes, because they’re used as both a data structure scope, but also as an actual scope when you evaluate Bass code.

So if you, for example, take like a JSON scope, like a scope that was like parsed from JSON, you can actually evaluate Bass code using that as like the runtime environment. A lot of the times where I try to – anytime I see enough similarity between two concepts, I actually try to just magnetically put them together, and so far it’s been paying off. I’m sure it’ll blow up in my face by like over-leveraging one concept in some interesting way… But I’m hoping that the fact that Bass is kind of restricted to one domain - I’m hoping that keeps it like low likelihood of too many footguns emerging from my overuse of concepts.

Well, the thing is you never know until you keep trying and keep getting to a point where you realize “You know what - this doesn’t work.” And that’s okay. As long as you have a fitness function that can determine whether what you do gets you closer to where you’re trying to get to, that’s okay. If it says I’m closer, then I am closer. Unless the function is wrong, but I think you would know if the function was wrong, because that’s really fundamental. And I think in your case, the fitness function is “Is it fun? Am I having fun with this?” And that’s like instinct. You know whether you’re having fun. It’s very difficult to game that. There’s no amount of anything that you can do other than just be honest with yourself with your delivering towards that goal.

[01:16:12.06] So I see that, and I’ve noticed, that there is a lot of Nix… And I don’t want to say a lot of, but like a significant amount of Nix in Bass. What is the relationship between Nix and Bass, the language?

So this is something I’ve been very careful about, because I know Nix is one of those things where the mere mention of it near your project can send people like scurrying and running to the hills and trying to avoid it, because some people see it as very complicated and hard to get into. And I think they’re right, but there’s a lot of really cool parts to Nix that are hard to find anywhere else. To me, the biggest value to Nix is having just the largest and most up to date software package repository in the world. There’s actually a dashboard managing this and comparing Nix to Debian and all these other systems… And it’s just like, Nix is like so far removed from them, it’s not even funny. They have things that are just literally automatically updating packages in the repo.

Where’s this dashboard? Because I haven’t seen it, and I’m very curious.

I think I put it in the release notes for the first release where I started…

For Bass 0.1.0.

Yeah.

There’s something which I need to mention here. DJ, Daniel Jones, congrats for your first pull request to Bass. We go a long, long way back, and seeing you as the first contributor to Bass put a smile on my face. So if you’re listening to this - and if you’re not listening, that’s okay. I’ll make sure that I send you a link with this episode… Maybe even the exact timestamp. Well done for doing the first contribution to Bass; that was very nice to see. Cool. So I’m looking at the 0.1.0…

0.2. I just put the link in the chat as a shortcut. My machine is really suffering…

10 minutes? More than 10 minutes. 15 minutes? More than 15 minutes. 17 minutes, I think.

This is like a – it’s a 2018 MacBook Pro. So it’s not even M1,

Right… Couldn’t you have run it on like your Ryzen? Because that’s what you have; you have Ryzen 7, I’m imagining…

That was the plan… But when I did that, that’s when like everything disconnected, so…

Oh, I see. So when you SSH into it, it doesn’t work, if you were to SSH…

I don’t think I have SSH set up. I was just switching the display. I have like a KBM button… But I forgot that everything else is also flowing through it, so…

Oh, I see what you mean. I see, I see, I see. Okay. Repology.org. Wow, that is impressive. Number of packages in repository, number of fresh packages… I see what you mean. I see what you mean. [unintelligible 01:18:50.29] I’m looking for the number of packages, number of freshness, and I can’t find – in that graph, I can’t find Nix. And I don’t think I can search, because it’s generated. This is rendered.

Oh. It should be very top right, on the first graph. You’ll see Nix packages unstable.

I can see that. And yes, stable. But on the second one – yeah, what is that, by the way? It zooms in onto smaller repositories… Oh, it’s actually outside of that. So that’s like a zoom in. It’s outside of that. Wow…

Yeah.

And that’s zoomed in some more… Homebrew Casks… Wow, that’s so far away. That’s so far away. Okay, that’s really cool.

To be fair, I think there’s a lot of automation driving this. There’s probably like – maybe they’re representing Python libraries and things like that as big packages. I’m not sure. But it’s still – usually, when I want some software, it’s in there, it’s up to date. If something shipped, it’s been up to date as of a few days after it shipped… Which is really what I’m looking for when I’m trying to build images and run things with Bass, is I want something that’s just like “Give me the latest version. I don’t care about sticking to Debian.” If I wanted Debian, I could just use Debian [unintelligible 01:20:09.22] install, or whatever… But the nice thing is that Nix also gives you precise reproducible builds.

[01:20:16.24] So interestingly, I have my Linux system, I switched it to – and I have like a couple of workstations… One of them is this NixOS host. It’s an AMD Ryzen 7. It’s a completely fanless system. I really liked the whole – like, configuring it was really nice. It has like a desktop interface. I just used some dashboards on it, Grafana dashboards to monitor my connection, my internet connection, things like that.

On a Mac, I tried installing Nix, and I have tried running it for about seven months. But it has this weird – I don’t know, I couldn’t get updates to work consistently. Updating the channel didn’t work. There’s this Darwin extension or something like that, that you need to install. That was a bit weird. So my question to you is, do you use Nix on Mac?

Actually, for my development, I use WSL. So I just use Nix within Linux, within Windows.

I see, okay. That makes sense. Okay. So you have basically all three on your Mac. The host is Mac –

The host is Windows.

The host is Windows.

The host is Windows, yeah.

Okay. Okay.

I’m just using Mac right now, because it has the Opal software from my webcam.

Oh, I see what you mean. Okay. Okay. Okay.

So the whole reason for this being horrendously slow, and like fumbling through all this is, that Opal doesn’t have software for Windows right now.

Yeah. I see. Okay, that makes sense. That makes sense. Okay. But Windows is like your host operating system, in that you run Linux, and all development works. happens in Linus. Okay, that makes sense. And Linux - I’m assuming you’re using NixOS. That is your host – so that’s your Linux operating system.

It’s Ubuntu with Nix, just for the package manager.

Interesting. It’s honestly pretty cobbled together. I only started using Nix once I had already started building Bass, so I was already using Ubuntu and everything for that… So I just wanted to see how Nix might interplay with Bass, I guess… I never finished that thought, by the way, which is that I don’t want Nix to be a dependency of Bass, because that would be terrifying to people, to have to not only learn my esoteric Lisp, but learn this esoteric Nix language beneath it… So it really only leverages it insofar as I as the project maintainer use Nix to build the images that feed into Bass. And I use Bass to build those images using Nix.

So Bass just sees Nix as another command to run. I’m just running Nix build, and then that produces an OCI image tarball, and then I passed that to another thunk… Because you can use thunks that use archives built from other thunks as an image.

Right.

One other thing I’ve been experimenting with though is because Nix is so good for just like pulling in packages as dependencies, and a lot of images that people build for CI are just - I need Ruby installed, or I need… But I don’t need just Ruby, I need like Ruby, plus Git, plus Upx, or like whatever toolchain I use… Because it’s pretty rare that you can just use Ruby off the shelf, like the library Ruby image, and have that provide everything you need… So one thing I’m planning to experiment with is having Bass - just like it starts BuildKit, have it start a Nixery host, and then you can just do like from Nix/gh/ruby/go and it’ll just build an image on the fly, with all those dependencies.

I want that. That is so cool. Oh, wow. That would be so cool.

Yeah. No more like building throwaway images.