Tim Hockin and Aparna Sinha joined the show to talk about the backstory of Kubernetes inside Google, how Tim and others got it funded, the infrastructure of Kubernetes, and how they’ve been able to succeed by focusing on the community.

Featuring

Sponsors

Sentry – Get 30 days free when you sign up with the code changelog. Error reporting and notifications for JavaScript apps and the rest of your stack. Start tracking errors for free. Support for React, Angular, Ember, Vue, Backbone, and Node frameworks like Express and Koa.

Hired – Get hired. It’s free — in fact, they pay you to get hired. Our listeners get a double hiring bonus of $600.

Datadog – Cloud-Scale Monitoring — Monitoring that tracks your dynamic infrastructure and applications. Plus next-generation APM. Monitor, troubleshoot, and optimize end-to-end application performance. Start your free trial, install the agent, and get a free t-shirt!

Notes & Links

Transcript

Play the audio to listen along while you enjoy the transcript. 🎧

Welcome back, everyone! This is The Changelog and I am your host, Adam Stacoviak. This is episode 250, and today Jerod and I are talking about Kubernetes (k8s, as it might be better known). We’re talking to Tim Hockin, one of the founders and core engineers of Kubernetes. Also, Aparna Sinha, lead product manager. We talked about the back-story of Kubernetes inside Google, how Tim and others got it funded. Tim also did a great job of laying out the infrastructure of Kubernetes, as well as how they’ve been able to succeed by focusing on the community.

We have three sponsors today - Sentry, Hired and DataDog.

Alright, we’re back. We’re talking about Kubernetes today, Jerod! K8s!

Kubernetes, that’s right.

The coolest acronym.

Yeah, and thanks to Bob Hrdinsky at Google for contacting us and saying, “Hey, you should do a show on Kubernetes.” Now, we’ve done a lot of shows kind of about Kubernetes (kind of) on GoTime, so if you’re into containers and Kubernetes in Go and all those things, definitely check out GoTime.FM, especially episode 20. Kelsey Hightower came on that show and that show was actually dedicated to Kubernetes, but most of the times it just gets brought up in passing, but never on the Changelog, Adam.

No, never. Like, zero.

Zero on the Changelog, so we’re very excited to have a show about Kubernetes. Today we’re joined by Aparna Sinha, who’s the senior product manager at Google and the product team lead at Kubernetes, as well as Tim Hockin, who’s one of the O.G. software engineers on the project. Tim and Aparna, thanks so much for joining us.

Thanks for having us.

Tim, do you like being O.G.?

I love it.

Who doesn’t like that? I mean, come on.

Howdy, Aparna. How are you?

Very good, thank you.

So great to have you, guys. Who was it that started this software, Jerod? Was it Bob?

Bob.

I love Bob. He’s awesome.

One of the things we like to do, especially with a project which is kind of a story, as Kubernetes is - first of all, let’s just state what it is, for those who are uninitiated… It’s an open source system for automating deployment, scaling and management of containerized applications. One of those cloud things, trying to make the cloud easier.

It has a storied history, but most of that history it sounds like is from the inside of Google, before it was open sourced. In fact, on the Kubernetes homepage it states that this results from 15 years of experience running production workloads at Google. And it actually beat out a few other systems - Borg and Omega, internal things at Google; there’s a white paper on that, which we’ll link up to as well - to get where it is today. Tim, I think you’re best positioned to tell us the story of how Kubernetes won inside Google, why it was open source, and all that good stuff.

[04:03] Sure. So I should clarify, Kubernetes is an offshoot of the Borg and the Omega systems. What we use inside Google is still Borg and Omega.

Okay…

Borg has been around since 2003-ish, when it was really a [unintelligible 00:04:18.13], and that was about it… And nice. So people were trying to find ways inside Google to share machines, because dedicated machines per service in production was pretty expensive and not really efficient, so we started this thing called Borg, which was really there to schedule work for people and to try to pack machines a little more tightly. Since 2004, so over the last 13-14 years, we built out this Borg system and we’ve added a lot of really neat functionality; things like cgroups in the Linux Kernel came out of the Borg team. We’ve added all these extra capabilities to the Borg system, but it was very bespoke. It’s very internal-focused, and it’s tied to the way Google does things.

We have the power here to send an email and tell everybody in the company “You have to recompile your application because there was a bug in the core library.” So people inside Google - myself included - couldn’t fathom living without Borg in the outside world; we’d always toyed with this idea of “What happens when we leave Google? Will I have to rebuild Borg? How will I live?” and when Docker landed in early 2013, we looked at this and said “Well, this is kind of Borg-like. This is containers”, and we understood sort of viscerally that people were very quickly gonna have a lot of the same problems they had in Borg, and we said “We know how to solve that. We’ve done it three times already.” So that’s when we started looking at Kubernetes as a way of rebuilding a lot of what we did in Borg, but building it in a way that wasn’t tailored to Google specifics, that was really there for open source, for applications like Apache and NGINX and MySQL, which aren’t Google applications and don’t use our Google RPC libraries. That brings a different set of constraints to the problem, so that’s why we started building in 2013 and into the beginning of 2014, and this is what became known as Kubernetes.

Kubernetes internally isn’t in great use, although we are seeing more and more teams now start to port their applications to our cloud product on top of a container engine.

So was Borg or any parts of Borg ever open sourced, or was there just a white paper? I remember there being a few years back a lot of news around this Borg thing coming out of Google, and that might have pre-dated Kubernetes open sourcing. Can you help me out with the history there? Was Borg or parts of Borg ever open sourced?

The way Google’s codebase works is we have a mega codebase. Parts of Borg have been open sourced in the sense that some of the core libraries that Borg uses are used by other open source projects, so pieces of this system have been released, but not as a scheduler or a container system per se. We did do a paper on Omega, and then we did a paper on Borg. We also did some papers and performance analysis of Borg and using application traces through the system to model the behavior of Borg, and in fact, some of these are in fact what led to the development of things like Mesos.

Very interesting. Oh, that does ring a bell.

I do wanna add one item here. First of all, I think we’re very fortunate that we have Tim Hockin to talk to us about this, because he is originally from the board team and he’s been at Google for many years (10+ years).

Absolutely.

The other point I wanted to make is that, you know, what we found is that when you talk about open source systems, there’s a fundamental difference between taking a technology that you’re using internally and open sourcing it versus developing something as an open source platform from the get-go. Kubernetes is the latter. When you take something that’s internal and open source it, it’s not necessarily built for an external environment, and it usually has a number of constraints built into it that may be specific to the company from which it comes.

[08:13] The Kubernetes was built differently, and I think Tim can speak much more about that… But it was really built for the external world, with the external world from the start.

On that note though, we’ve heard the story of people being inside of Google, and then as you said before, Tim, kind of stepping outside of the Google land and no longer having those Google tools, and what would life be like without those… We’ve heard that story before, so it seems natural to white-paper Borg and provide that out there when Docker came to fruition, but then also feel like you have a problem solved with Kubernetes and release that as a full-blown open source-focused project.

Yeah, we like to joke that Google has been playing a long game for the last 10 years by teaching everybody who comes to work at Google how to use Borg, and then when they leave Google, they’re out there aching for this thing, for Borg, and then we produce Kubernetes.

Right, that’s a heck of a long game, for sure. Tell me about open source – even the white paper. I feel like we may have been down this road a little bit with Will Norris or somebody else from Google, Adam, that I can’t think of their name, but I’m looking at Borg as an insider, and I’m thinking this is a system that we can run our entire organization, and people long for it when they leave. That means they don’t have it other places, so that feels like a very strong competitive advantage to an engineering culture, so why even expose it at all? Why not just keep it all inside?

That’s a great question, and in fact it’s exactly what [unintelligible 00:09:40.20] asked us when we brought it to him. [laughter] In the history of Google, we’ve done a bunch of these patterns where we release a paper talking about how excellent this idea is - MapReduce, or GFS, or Bigtable… And we put out a paper that says “This is how we basically built it, this is how it works, and it’s amazing and it’s changed the world” inside Google, and then somebody outside goes off and builds it, and they build a different version of it that’s not really compatible with what we’ve done, that may be technically equivalent or technically inferior, but it doesn’t matter, because when you look at something like Hadoop, that’s what the world uses, right? And it doesn’t matter if MapReduce is better or not… When we hire a new engineer, they know how to use Hadoop, and they have to come in and they have to discard a lot of what they already know to learn how to use what we do internally.

The way I see it is the closer systems get to each other, the more energy you need to keep them from merging. What we saw in 2014 is container orchestration is going to happen. The world is – they’re coming to their senses with respect to containers, they see the value of it. Docker happened faster than anybody could have predicted, right? People were seeing this, but we knew that as soon as they run a couple of these things in production, they were very quickly going to need tools, they’re gonna need things to help them manage it. We could either be part of that, or we could choose not to be part of that, and that was what the Kubernetes decision was really about.

That makes a lot of sense. That’s reminding me very much – Adam, can you help me out here? We did an episode, and I feel like it was with Google, but it might have been with James Pearce at Facebook, where it was one of these inevitable things where this was going to happen, and we know it’s going to happen, and they’re either going to do it around a set of tools and processes and ideas that we are in control of, or that we aren’t. And by “control” I mean influential. So the decision was really kind of made around that, as opposed to keeping it secret, because if there’s going to be an ecosystem, if there’s going to be a platform, it’s advantageous to have – especially once the white paper is out there, the toothpaste is out of the… What’s it called?

[11:54] Yeah, it’s out of the tube. I recall some sort of conversation around this… It may have been the public data set call we had with GitHub that was around Google Cloud; that might have been a part of that conversation, but I can’t place it. If you’re a listener and you know the show and we’re idiots and we just can’t figure it out, let us know; we’ll put it in the show notes.

Yeah. I just say that because I’m having a very strong sense of deja-vu as you’re explaining this to me, and I feel like somebody else has explained this to me and it made a ton of sense then. It makes a ton of sense now. So tell us the story about the rewrite. I cast it improperly… It’s not that it’d be Borg, it’s that it’s more like son of Borg. So all the good idea is here, let’s re-create - kind of a rewrite, but an offshoot, with complete open source in mind from the very start. What does that start to look like? Huge undertaking, no doubt. Borg grew organically over the years, and now you probably have a lot of pressure to produce something great in a small amount of time.

That’s very much true. Borg is something like a hundred million lines of code, if you count the entire ecosystem in it. It’s written in C++, it has been written over the course of 14 years by hundreds of engineers. It is an incredibly expensive thing to try to recreate, but it’s also alien technology. As Aparna implied earlier, we couldn’t just release Borg, because it wouldn’t be useful to people; so big and so complex and so done that nobody would be able to get into it. So we wanted to really go back to the beginning, start with some fundamental principles, start with some of the lessons that we learned from Borg, some of the mistakes we made, fix those, some of the things that work really well in Borg - keep those…

We had a bunch of decisions early on - when do we release it? The answer that we came to was “Well before we’re happy about it”, because we wanted to build community, we wanted to get people invested in it from the beginning. What are we gonna write it in? Google is a C++ shop for performance things, Borg is C++, but C++ has no real open source community around it, not in the way that C or Python (or Java, even) have communities… So we took a hard look at what languages were hot right now and fit the space that we wanted to go, and we chose Go.

I was personally a very reluctant Go adoptee; I was a C++ fan, I liked the power of C++. In hindsight, choosing Go was absolutely the right decision. The community around Go is amazing, the tooling is very good, the language is actually really good; I get a lot of work done really quickly. So these were all decisions that we had to make at the beginning, right? Do we build it like Borg, where it’s RPC and protobuf based? Or do we do more open standards, so we went with Rust and JSON, because we didn’t want this to be a big incestuous Google lovefest… [laughter] It’s sort of funny that once gRPC launched, it’s gotten massive adoption, and now we’re getting asked to add gRPC support to it.

These were the key decisions at the beginning - how do we start his over? When we put out this idea, we went to DockerCon 1 in 2014 - I hope I’m getting the dates right - and we had a conversation with some of the fellow from Red Hat, Clayton Coleman in particular; we showed him what we were up to, and I think it resonated for him, I think he got it, and I think we were early enough that he was able to say “We can get involved in this, we can actually establish roots here. This isn’t a fully baked thing”, and I think that was the ground work for what’s turned out to be a really fantastic open source relationship, and the project has obviously grown a lot from there.

And I wanna add one thing… You talked about differentiation and the technology with Borg being a differentiating technology and why don’t we open source that - you know, we actually view the community that has developed around Kubernetes and the fact that it is a community-developed open source product as a differentiator for Google Cloud.

Yeah, that’s a strong point, because you can imitate features, you can copy features, right? But momentum and community and ubiquity is something that’s very difficult to get from a competitive advantage.

Right.

[16:08] Yeah, good point.

As someone who’s on the receiving end of a lot of the pull requests from our 1,100-1,200 contributors, it’s amazing and overwhelming, and the project would be an entirely different thing if we had even half of that many people.

While we’re still here in the history point of this conversation, you mentioned in the pre-call that you were one of the founders of Kubernetes, and you mentioned the funding process or getting this project funded by Google… What was that process like? Can you take us back to what it was like, how you sold it, how you all sold it, whatever the process was?

Yeah, sure. Early on there was a prototype that was put together by Joe Bada, Brendan Burns and some other engineers inside Google, just to prove out some of the ideas that we had pushed forward through Omega. For history, Brian Grant was the lead developer, designer of Omega and he had some interesting ideas that were different from Borg. So Brendan and Joe and Craig and Ville took those ideas and they sort of glued them together with some Go and some shell script and some Docker and some Salt, and they took all these open source things and they threw them together into a very rough prototype, and they showed us at one of our joint cloud infrastructure meetings, and my jaw hit the floor. It was like “This is awesome. This is amazing. It’s a little rough around the edges, but that’s incredible.”

Then it sort of sat on the shelf while we tried to figure out what to do with it. Docker was this brand new thing, we didn’t know if it was really gonna take off or not, we weren’t sure how we were going to staff this, the organization wasn’t really behind it, cloud was still very immature at Google, and we had a bunch of other sort of false starts on how to make containers in Google Cloud a better place. It was later in 2013 when we said “We really think the answer here is to build this Kubernetes thing.” It wasn’t called Kubernetes at the time, but we decided to take this thing off the shelf and dust it off and make it into a real product. So we started on the process of that and we did an internal product requirements doc and we brought it to our VPs and we showed them the ideas and we made our pitches, and we understood their concerns about what was giving away the golden goose and what was okay to talk about and release. We had sort of our rules of engagement, and that was how we got towards the Kubernetes announcement that we made at DockerCon 1.

Initial release, 6th June 2014. Does that ring a bell for you?

That’s right.

There you go, so I’m assuming that was your DockerCon 1. Very good, that’s a great history. I think we definitely have seen why and how it came out of Google. By the way, Borg is the best name ever. We’ve heard there were some argumentation around Kubernetes and how to pronounce it, what’s the name, but Borg is an excellent name. Actually, Tim, real quick before the break, can you give us a little insight on Kubernetes the name, its meaning…? I think there was even like a Seven of Nine, or something… Tell us that.

Right. So the initial name of the project was Seven, in reference to Seven of Nine, which is following in the Borg Star Trek tradition. Like all good geeks, we name things after Star Trek. And Borg really is the best codename ever, we’ll never do better than that.

It really is.

Seven of Nine was the attractive Borg…

[laughs] I like that, it’s even got an angle on it…

So we called it Seven. Obviously, that was never gonna fly with trademark, so we had to come up with a real name. Honestly, there’s no magic behind the name… We all came up with synonyms and translations, and we just dumped them all into a doc, we threw out the obviously terrible ones and we sort of voted on what was left, and Kubernetes was the winner.

[20:06] As a word, it means “helm’s men” or “the guy who steers the boat”, which has been keeping with the nautical theme that Docker put forward, but also capturing a little bit of the “We’re managing things, not just shipping things”, so we liked the connotation of it. It’s fairly SEO friendly, it’s memorable, so it sort of fit the bill for everything we wanted, except for brevity… So that’s why Kubernetes became K8s.

I wanna point this out too, Jerod, that he said it’s SEO-friendly, and I never would have thought that Google would care if something was SEO-friendly, because…

Well, they’ve gotta play by their own game, right?

I suppose.

They can’t just pull in everything at Kubernetes.io.

Exactly, we never ever manipulate search results, so it had to be organic.

This is not an episode of Silicon Valley. [laughter]

I mean, compare, for example, Go…

Oh, big fail.

…which is the least SEO-friendly world in the world. We had to invest a new word just to be SEO-ed - Golang.

Right… Not to mention all the namespace clashes on Go, since it represents a game, and a drug, and many other things. Okay.

And the logo… We should say the logo still retains that reference to the number seven.

That’s right.

What’s the logo?

Our logo is a blue heptagon with a seven-sided ship’s wheel.

Oh… You all are so nerdy, I love you so much. I love naming and I love nerdy names, and this has it in spades. I actually think it’s kind of cool, like i18n - it took me a long time to figure out that was internationalization, because there’s 18 letters in between. K8S… It’s almost like an inside baseball type of thing - once you’re on the inside… It’s kind of cool to have to have one of those, so even though it’s too long, you won there… Although I mentioned there’s controversy now; we’ll be talking a little bit about KubeCon, which bothers me, because it’s Kubernetes, but it’s not CubeCon. Tell us about the controversy real quick, and then we’ll take the break.

Well, it’s a non-English word that’s being pronounced primarily in English. As tends to happen when you englify those sorts of things, they get changed, to be polite. So Kubernetes is the somewhat obvious pronounciation of the full spelling, but when you abbreviate it to just Kube, then the English word “cube” immediately comes to mind, and it’s much more approachable to call it “Kube” [kewb] than “Kube” [koob], so KubeCon [KewbKon] seemed to be the obvious thing. Now, there’s plenty of people out there who call it KubeCon [KoobKon], who jokingly spell it K00b, and we even have heard Kube [koobie]…

Wow…

If you wanna get even more into the argument about pronunciation, you can talk about how we pronounce the name of our command line tool.

…which, please do… While we’re here, we might as well…

The command line tool is KubeCTL, so KubeControl is sort of the longest form. I tend to say KubeCuttle, other people say KubeSeeTeeL, other people say KoobCuttle… Every variant that you can come up with has been tried, so…

KubieCuttle…

That’s a good one.

What else would we have to talk about if we couldn’t argue over pronunciation?

That’s right.

It’s the classic programmer bike shed, and we all love it so much.

Must argue about names.

Alright, we are back with Aparna Sinha and Tim Hockin from Google, talking about Kubernetes. We got a little bit of the history and the why it exists, but one question that I always have is who is this for, and what are some places where Kubernetes or this kind of infrastructure could really shine? Aparna, it sounds like you have a couple of stories for us to help us understand how companies are using this and how it’s useful for them, so go ahead.

Yeah, I sure do. Kubernetes is for a variety of different users, and I think that it applies to most environments actually, but I’m gonna give you a few examples, both from our hosted Kubernetes offering on Google Cloud - which is called Google Container Engine - as well as from the open source Kubernetes offering. The distinction there is that the open source Kubernetes offering is deployed on customers’ premises and in other clouds that they may be using in addition to Google Cloud.

Just a few vignettes of types of use cases… We’ve seen users that are using Kubernetes as they migrate from say AWS to Google Cloud, from a VM-based infrastructure to some things as a container-based infrastructure.

One of the examples that we did a webinar on - actually, I did the webinar about a year ago - is [unintelligible 00:26:32.23] They’re a good example because they’re kind of a startup, they have a web frontend, they’re in a business where speed is really important, deployment speed in particular and how they respond to customer needs. What they did is they moved from a VM-based infrastructure where their utilization was quite low actually - it was less than 10% because of quite a bit of over-provisioning, and this was on AWS, and they really didn’t have reliable auto-scaling. They moved to a containerized architecture here on container engine, and one of the immediate benefits that they saw was of course the increase in utilization, because they did and they were able to use Horizontal Pod Autoscaling - we call it HPA - in Kubernetes on a container engine.

But the biggest benefit that they noted was how simple it was to deploy their application. They noted that they could go from commit to in-production in less than three minutes, and that they would do so 30-50 times a day with no risk and no downtime. This is very important if you have a web frontend or any kind of end user-facing application. We found that the benefits of deployment speed are critical to the business.

So that’s one kind of customer, and I think you can apply that to many situations - you can apply that to eCommerce and retail; we have many users that are retail and eCommerce users that use the container engine offering in addition to some of the analytics offerings that are also on Google Cloud.

[28:09] Another favorite story that we have here in the Kubernetes community and at Google is that of Pokémon Go. I think that that’s also a great example, because it applies in general to gaming. We do have many gaming vendors that use Kubernetes. In their case, you don’t know really whether a game is gonna be a hit or not, and having a flexible infrastructure that can scale up as you grow and then scale down when you need to is really very cost-effective and also doesn’t stunt your growth when you need it the most. I think Pokémon Go definitely is the fastest-growing application to a billion dollars that the world had ever seen until then, and Kubernetes is behind scaling that up.

Yeah, I mean Pokémon Go was beyond successful. It was a phenomenon last summer, and even with Kubernetes, they had some issues. They were scaling, but at a certain point your demand is just increasing at such a rate that all the preparedness in the world may not be enough.

Yes, there were definitely some issues that they had because they weren’t really prepared for – it was well beyond what they had anticipated. But from a technical perspective, we were able to help them meet that demand, and continue the growth in time.

Were they coordinating with you before release? Obviously, there’s some dev time there, so how close was the relationship of them planning the need for scale - or even the potential need for scale - and the infrastructure to be built on?

Yes, there was communication beforehand. The truth is that there was no – it beat all forecasts. Actually, Tim, do you wanna add here? You were also involved in the Pokémon Go story.

Yeah, it was sort of funny, because I’m not a Pokémon fan, I’m just a little too old for that… And I came in to work and that was all over the radio, it was all people were talking about, all the interns were talking about, and I was like “Gosh, I’m so tired of hearing about this Pokémon thing” and they said “You know it’s running on us, right?” and I said, “Oh…” [laughter]

“Keep talking, please…”

So that was the same day that we got a request from our Customer Reliability Engineering team (CRE) that Pokémon would like us to engage a little more and help them figure out how to scale better using the Kubernetes product. So that day we started getting involved and answering some of their questions and helping them figure out how to manage their deployments a little bit more effectively.

They were absolutely pushing the limits of what we were offering right out the door – I mean, this was a pretty early Kubernetes release, and they were pushing the bounds of our max cluster size, and there were a million things that they were doing that we said “Oh, goodness… We say that that works and that’s supported, but you are right up against the edge”, and they wanted to go bigger. This was before the Japan launch, this was before most of Europe had been turned on… So we engaged with them to help figure out how to manage their Kubernetes resources, and it was actually really an amazing experience, because their team is also super talented. But we would have all our calls late at night because their usage was relatively low and they were making live changes to the system, and at some point we had to ask them “Slow down on the changes”, because it was just so easy for them to make changes through Kubernetes, and we had to let things settle and figure out what the right ratio is between frontends and backends. So it was an interesting opportunity for me to watch somebody actually use our product.

Yes, that’s a great story.

[31:49] Kubernetes, like you said, is being deployed [unintelligible 00:31:50.15] slowly into Google, because Borg has been running Google-wide for a long time… But perhaps Pokémon Go was stressing Kubernetes, like you said, obviously a lot, but maybe more than – you know, you assume “Well, Google’s making this, so this is Google web scale - or whatever the word is - and it could Google-type traffic”, but it really hadn’t been tested maybe as much as it was with Pokémon Go. Is that fair?

That’s absolutely true. One of the hard things about working at Google is you can’t launch anything until you’re ready to handle a million users, and we don’t have that same requirement with Kubernetes. If we had that same requirement, we never would have shipped. We went out very, very early in terms of capabilities. The Kubernetes 1.0 supported 100 nodes; 100 nodes is barely a test cluster inside Google. So by the time Pokémon came in, we were supporting 1,000 nodes and they were pushing the limits of what we could support, and we were worried about what they would need when they turned on Japan.

How did that work out when they turned it on? Was it ready for it?

Oh, yeah. The Japan turn up was really smooth, actually. By the time Japan came online we’d worked out most of our major issues, we found the right ratios and figured out how to defeat the [unintelligible 00:33:15.10] of service attacks. In fact, I think I was at San Diego Comic Con when they turned Japan on and it was just a non-event, nothing happened.

That’s right.

Wow.

That’s the way to be right there.

And we were at 2,000 node clusters at that time, and now, just as of our latest release, we’re at 5,000 nodes.

Wow.

That’s very cool.

But it certainly ties into the three big features you have on the website. You can’t go to Kubernetes’ website (Kubernetes.io) without seeing “Planet scale. Never outgrow. Run anywhere.” This is like your promise to anybody who says “I wanna use Kubernetes.” We could get into the details of how this actually plays out… How do you actually achieve these features?

So there’s the scalability issue. We promised that people won’t outgrow; now, 5,000 is a lot of machines, but it’s not a super-lot of machines. It wouldn’t satisfy the googles and the twitters and the apples of the world, but those are not really the market that we expect to be adopting Kubernetes… At least not whole hog, not yet. If you look at a histogram of the number of machines that people are using, 5,000 is well into three or four nines territory. We’re trying to address those people. It is designed for that, and we offer 5,000 with a pretty good service agreement that we test the API responsiveness and we ensure that it’s less than our acceptable time, so people can use it at scale and not be disappointed in it.

We could probably tell people that it worked at 10,000 nodes, but it just won’t work well. We test it, we qualify it at 5,000 nodes, and we have tests that run on a regular basis that tell us “Hey, you’re falling out of SLA because somebody has a performance regression.”

This SLA though is at the Google container engine level, not so much Kubernetes itself, is that right?

Kubernetes itself, we say that for this particular archetype of workload, you will get this level of service from our Kubernetes API server whether you’re running open source or on Google Cloud or on Amazon or on your bare metal; this is what we’re shooting for to say that we support 5,000 nodes.

Gotcha.

Google Cloud offers an extended SLA on top of that.

Gotcha.

Yeah, the 5,000 nodes is an open source and Google container engine number, and it’s measuring SLOs - one on API latency and another on pod startup time. Both of those are fairly stringent SLOs. We do have users outside of Google Cloud that run larger clusters.

[35:56] But one thing that I would point out is that when I’ve talked to the largest of large customers that are interested in using Kubernetes, usually they’re looking at multiple clusters, and I think that’s also part of the planetary scale aspect. They’re looking at, say, having multiple regions that they want to have a presence in, because they are a global company, they have users – I mean, Google obviously is a global company, and any one workload may be running out of multiple regions so that they can have lower latency to the users in those regions. That typically - certainly in a cloud context - involves multiple clusters. You may have a cluster in the Asian region, you may have a cluster in the Europe region, you may have another one in North America, each of which could be as large as 5,000 nodes. Typically, actually I see less than that - 1,000-2,000 nodes for the large customers, and then spanning that workload across multiple clusters, which may or may not be managed together. You could manage them independently, or we also have what is called cluster federation, where you can manage them from a single endpoint.

I was gonna ask if that level of scale where you’re not just scaling out nodes, but you’re actually scaling multiple clusters regionally - if that’s seamless with Kubernetes. There’s a couple different ways of going at it, but there is some configuration involved in getting that all working together?

Yeah, we’re working on the federation product… We’ve got a team in Google and in the community who’s working really hard to make federation - maybe “seamless” is too grand, but to make it really easy for people to say “Look, I want my application deployed on three continents, and I want it in this particular ratio (based on a customer base). You go manage it and make it so, and if something fails in one zone, make sure that it overflows into another zone.” The federation product does this today.

When it works, when you understand the bounds that it operates in, it’s pretty magical, I’ve gotta say. It does things that actually we don’t even do inside Google. A lot of this is done manually inside Borg, because Google likes to have a lot of control. Again, this goes to, like, changing the constraints, and for people in open source, “Just put me one in Europe and put me one in the U.S.” - that gives people a huge win in terms of latency.

The other reason that I’ve seen some of our customers - and I was gonna mention Phillips, actually, as we were talking about use cases… Phillips is an IoT customer (internet of things) - they make these IoT-connected lights - and I was gonna mention them because a lot of European companies have like a data locality or they wanna keep their users’ data, certainly for Europe, within Europe, and then they wanna have another cluster in the North America… Certainly for lower latency, but also because they wanna keep the data there. So there are multiple reasons why our users tend to want multiple clusters.

So we’re talking about “Run anywhere” as one of your main features on the homepage – I mean, this is “run anywhere regionally, or around the world”, but somebody pointed out it doesn’t just mean that, but also run on any cloud infrastructure, right?

Yes.

You don’t have to code specifically against Google Cloud or against Amazon. You’re [unintelligible 00:39:12.11] a level above this, so now we’ve decoupled from our cloud provider; it gives us choice… Doesn’t that commoditize Google Cloud as a product, and really – wouldn’t you prefer vendor lock-in, as opposed to what you’re providing everybody, which is the freedom of choice?

Can I go first here? I wanna touch up on the “Run anywhere”, because just stepping back, one of the promises of containers is portability, right? Your application is no longer tied to a particular hardware or to a particular hypervisor or a particular operating system, to a particular kernel. So you can actually move it from cloud to cloud; you can move it from on-premise, you can move it from your laptop to the cloud. That is the promise of containers. However, if you don’t have a way to manage containers in production, that also is portable, so the container manager also has to be portable in order for that promise to come true. Otherwise, that promise sort of breaks down.

[40:14] So when we say that Kubernetes runs anywhere, we really are referring to that aspect of portability, that your container orchestrator, the thing that manages your container environment in production can run in all of those environments - it can run on your laptop, it can run in your public cloud of choice and in your private cloud of choice.

I think Tim will say - it’s not necessarily zero work to move your system from one cloud to another, but your applications and your services that are designed to run on Kubernetes will run on Kubernetes anywhere.

That’s right. We spend an enormous amount of time making Kubernetes not couple to the underlying cloud provider. The reason we do that is we hear that this is what people want, this is what customers are asking for, so something that was coupled to Google Cloud was just not going to be a winning product, where winning here I think really means ubiquity. To make it a really ubiquitous system and a thing that people can assume exists, it has to be viable in all sorts of places. We personally spend time making it work on our competing clouds, we have partners in the other public clouds that work on Kubernetes, we also spend time making it work on bare metal, we help partners in other companies do things like support enterprise customers on bare metal, the idea being that if you write your application to the Kubernetes APIs, then you can pick it up and you can move it wherever you want, and that’s a real choice.

The flipside of that is it is a ton of work from an engineering point of view to make sure that all of our APIs are decoupled, that we don’t add things that aren’t practically implementable on other platforms… These are things that we consider every time somebody sends us a pull request.

Yeah. And I think from a strategy point of view, we wanna be where our users are. I think if you look at infrastructure span today, the vast majority of it is on premise, so we wanna make sure that we’re building a product that meets users where they are, and that’s been the philosophy with Kubernetes from the start - we meet them where they are, we provide them the best infrastructure, then they’ll naturally come to us.

Well, we love it as end users as well, because what it does for us is it puts really the vector for competition where we care about it for these different cloud providers. They compete on things like price, and performance and reliability, and all the things that we want out of a cloud, and they’re not competing on this particular API, which the other one is lacking, because we don’t care.

Yes, that’s exactly right. I think the place where Google Cloud competes is we have the fastest VM boot times, we have a very impressive global network, we are doing deep integrations with the underlying network and Kubernetes, our hosted container offering. I think we have the best price performance, and you can use preemptible VMs, you can use custom VM shapes, you can continue to use discounts and so forth, all of them on our container offering.

That’s a good place to take our next break then, because we wanna dive a little further into things like architecture, which is a long subject, I’m sure. Let’s take this break, and when we come back we’ll dive further into K8s’s architecture. BRB

And we’re back, talking about K8s, and I said in the break I was dying to say “BRB”, and you can’t follow K8s and go into a break and not say “BRB”, so I did it, so thank you very much…

You checked that off your bucket list.

Yeah, there you go. Tim, Aparna, we’re back, talking about Kubernetes. You know, one thing that is probably hard to do - audibly, at least - on a podcast like this is to describe architecture. Tim, how often do you get asked this, and can you do it?

You know, on a pure podcast it doesn’t come up that often, because I gesticulate wildly and like to sketch on whiteboards, but I’ll do what I can. [laughter]

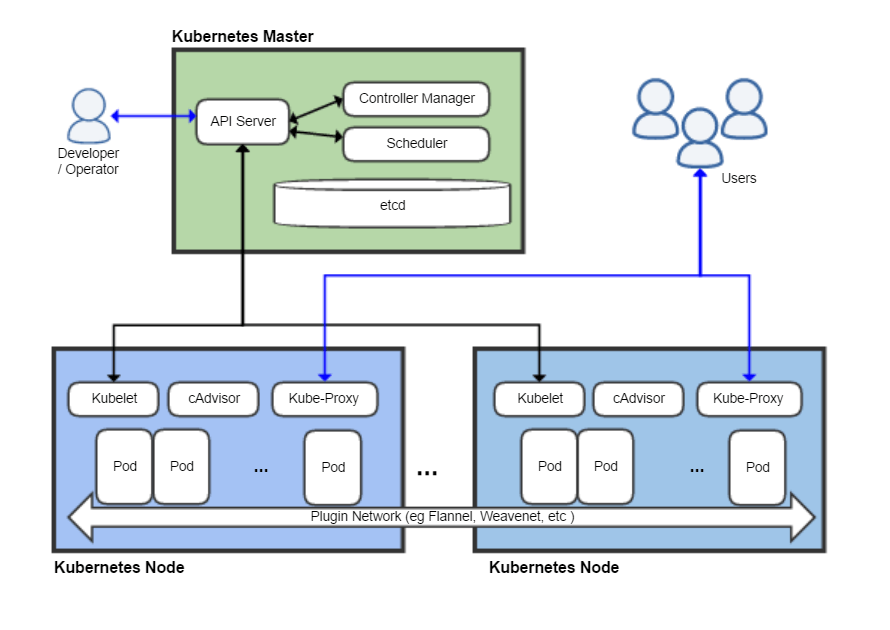

Well, let’s say this… We will include – there’s a nice diagram on Wikipedia, so we’ll put that in the show notes, which does lay out a few of the pieces. Hopefully it’s correct; it is Wikipedia, so it could be wrong, but as you’re talking, we’ll assume the listener can at least go look at the show notes and view that, and get some visual while you go through it.

Unless there’s a better version of it somewhere…

You know, I think we’ve been working on a new architectural diagram, but I don’t think it’s ready for primetime yet.

Oh… Alright. We’ll have to use that one, and you’ll have to smooth over all the rough edges. Go ahead, lay it out for us.

Alright, so Kubernetes is fundamentally an API-driven system, so at the center of our universe is this thing we call the API server, and it is a REST server - it’s a web server with REST semantics, and we talk in terms of REST resources or our objects, and those objects describe the various bits of semantics of our system. Those are things like pods and services, and endpoints and load balancers, and those sorts of things.

Each machine within your cluster has an agent that runs that machine. That agent is called the Kublet, following in the vein of Borg, which had its Borglet, and Omega, which had its Omelet. [laughter] So the Kubelet runs on every machine and it is responsible for talking to the API server, figuring out what that machine is supposed to be doing, which containers is it supposed to run, and then activating those changes.

The API server runs on what we tend to call the Master; it doesn’t have to be a single machine or a set of machines dedicated to this, but it’s the most common way that people operate. On the Master are some other components that run alongside it. One is the scheduler. The scheduler is just a consumer of our API. Everything we do consumes our API; there are no backchannels, there are no secret APIs… Everything uses the public API.

The scheduler looks at the public API and it says, “Hey, is there work in here that hasn’t been assigned to a worker? If there is, I’ll go do that assignment”, and that’s basically all it does. Then we have this thing called the controller manager, which implements a control pattern that we call controllers. What a controller does is it says “I have a job. My job is to make sure that a load balancer exists for this service. That’s all I do. And I watch the API server and I wait for changes, and when things change, I wake up, I activate whatever the thing that I was asked to change, and then I go back to sleep. Periodically, I’m gonna wake up and I’m just gonna check the state of the universe and make sure that it exists in the form that I expect it to exist. If it doesn’t, I’m gonna drive towards the declared state.” This is sort of the declarative model.

[48:30] So the controller manager implements all of the most common controllers that we have for our system. These are things like resolving endpoints for services, or managing nodes, making sure that nodes are healthy and doing health checks there. The scheduler itself is a controller… So all of these pieces wake up and they’re always talking to the API server constantly. If you were to watch the API servers logs, you’ll see that it’s constantly busy just answering these requests - forget these objects, put these objects, update this, patch that.

When you use our command line took, KubeCTL, it does the exact same thing - it talks to the API server, it gets objects and it prints them for you, it takes objects from your local files and puts them into the server, which then creates new things for the server to do.

For example, the most common thing people wanna do is they wanna run a container. We call that a pod. A pod is a small group of containers. As an end user, you can say something like “kubectl run –image=nginx”, and I’m gonna just go run an NGINX. That will generate a blob of JSON or protobuf that we tell the API server to post to a particular URL, and the API server says “Okay”, it validates the input, it writes it there and it says “I now have a pod that I have created. Here is the unique ID for that pod.” Now the scheduler wakes up and says, “Oh, look, pods have changes. Let me figure out what to do with this pod.” It says, “Okay, I’m gonna assign that to node #3” and it adds a field to that object that says, “Now you’re bound to node #3.” Now the kubelet on node #3 wakes up and says, “Oh, my information has changed. I’m supposed to go run this container”, so it pulls that blob of JSON or protobuf, it looks at it and says, “Oh, I’m supposed to run NGINX. Okay, cool. I will do a Docker pull of NGINX.” It will then run NGINX and it will watch it. If NGINX ever crashes, it will restart it.

There’s a million other things that are built into the pod specification, like health checks and readiness probes and lifecycle hooks, and we’ll do all of those things, but the basic idea of running a container is pretty straightforward - you post what you want to happen to the API, and all these other pieces wake up and collaborate, and make things happen.

I think the really cool part of this architecture is that it’s always easy to figure out what the user wanted to happen, because the state of things is declared - “I want there to be a pod, and I want it to be running NGINX.” I can then wake up periodically and say “Is that not true?” If it’s not true, let me make it true. And you don’t have to worry about “Well, a command got lost” or “A command got sent twice”, because it’s declarative.

Well, first I’m gonna say that was excellent - you just sold yourself short, because I’m tracking everything… I’m staring at this diagram, which makes it very easy to track. It’s at least currently still up to date, so check out the diagram as he explains this if you’re still confused; rewind and stare at it. But it’s interesting… I was wondering, because you said “I want an NGINX”, so I was like “Okay, how does it know what an NGINX is?” and you said it pulls from Docker, so the images are all Docker images underneath.

That’s right.

Okay.

And it could be in any repository. I mean, there’s a public repository, or you could be using Google Container Repository (GCR).

Right.

[51:54] Or you could use a private registry, or you could use the ones that Amazon ships, or you could use Quay.io… There’s dozens of these offerings that are Docker registry-compatible, and we will work with all of them. We have a way to specify credentials so that you can pull from a private registry and use private images.

And then I also noticed that – you know, we’re talking about the architecture, kind of the underpinnings here, and I just love to see when there’s other open source things that are involved, because nobody’s building these things in a vacuum, and you have Etcd being used for service discovery, which is a highly allotted tool out of CoreOS, which is very cool… So you’re pulling together things - Docker, Etcd, and of course all this custom stuff as well… At the end of the day, it makes very much sense from a command line, but surely there’s some sort of declarative way that I can define, similar to a Docker file – is there a Kubernetes file where I can say “Here’s what I want it to look like”, and I can pass that off and it builds and runs? Or how does that work?

Yeah, absolutely. The specification of our API objects in the end is just a schema, and you can use things like Open API, which is a specification – the follow-on to Swagger; you can look at that for sort of a meta description of what the schema is, and in the end you can write yourself a JSON or a YAML file that you just check into source control, and that is literally the exact same thing that KubeCTL Run does - it generates that same blob of JSON and sends it.

So the command line gives you a bunch of imperative commands for humans, but if you are really running this as a production system, what I would do is write the JSON or the YAML blob, check it into your source control, and then activate it on the server. There’s a separate command called KubeCTL Apply, which says “Take this blob of JSON in a file”, or you can actually have one file that has multiple resources in it. You can also point it at a directory, you can also point it at a URL, and “Go apply this configuration to my cluster. Make it so.” I wanted to call it “KubeCTL Make It So”, but… [laughter] The Borg analogies ran dry.

It’s like a wish machine, basically, and hopefully the wish can be commanded.

And that is how most customers run in production.

Right.

Yes.

Well, it makes sense to feel things out with the command, test and develop, and then once you have it figured out, then you do it with the Apply method.

Right. And in fact, we run our own website and some of our own tools on Kubernetes and we publish our YAML, so that people can look at how we run our own stuff. I think that’s sort of interesting for people. It has given us a sense of exactly what people are up against when it comes to things like certificates and things like Canary-ing… We’ve tried a bunch of different techniques for how we think best to use our own stuff.

Yeah. What would be really cool is if we could actually do a demo on the podcast, which is gonna be much harder. [laughs]

Yes, that is much harder, but hopefully we’re at least getting people’s interest piqued enough that they can go out to Kubernetes.io and watch videos or demos, or join a – I’m sure you guys have WebX’s, or whatever those things are called…

Webinars.

Webinars! Thank you.

Aparna was saying she just gave one a year ago, but do you give those more often?

We have many. In fact, there are many that Tim has done. There’s a whole YouTube page of his demos; we have hundreds.

Gotcha. So do you keep a YouTube is your log of past done webinars?

More or less… If you YouTube search for Kubernetes, you’ll find me, Brendan, Brian, Joe, who are really the founders of the project, but you’ll also find luminaries like Kelsey, who have done all sorts of really cool talks, generic 101 level sessions all the way down to deep dives on networking and storage and these other topics. They all tend to get posted to YouTube.

[55:49] I also post all the slides for talks that I do on my Speaker Deck, so if people wanna follow along, they can go look at my Speaker Deck and click through the slides on their own pace.

Very good. Send us that link and we’ll put that in the show notes as well. Lots of places to get more information for sure. Real quick before we get into community and kind of the getting started… We talked about scaling up, of course - that’s what Kubernetes and nodes and clusters is all about; planetary scale, web scale, whatever you wanna call it… The ability to not have to rush and have the ability to scale when you need to, which on the web you rarely know when that is… How well does it scale down? We’ve talked about some of your great users, but when is it too small for it to make sense, too much overhead or too much work to use Kubernetes? Or if you haven’t learned it yet… If I’m running a Wordpress site with maybe one or two servers, maybe a database and an Apache or something - is that too small for me to take the time with Kubernetes, or there’s still wins at that small scale?

There’s two things to scaling down. Obviously, I think when we talk about auto-scaling, I think you’re saying it auto-scales up very well. It also auto-scales down, just to clarify. But your main question is around “What’s the smallest scale of deployment that you would recommend?” You know, we even have users that are using one node. Typically, when you have one node, you don’t need an orchestrator. Two to three nodes, depending on how many pods you’re gonna have, it makes sense to have an orchestrator, it makes sense to have a management framework, especially if you’re running things in production.

If you just have one node with some number of containers, then maybe it doesn’t make sense to use Kubernetes. But I think anything beyond that…

From my own point of view, I actually do run my personal stuff on a single node cluster, and I do it because the command line tools are convenient and easy to use, and I know them very well, so it just makes sense for me. But yeah, one node is sort of the boundary where it maybe doesn’t make as much sense.

Sure. Not just one node, but yeah, do you ever foresee being beyond one node, right? If it’s like “One node forever” and you don’t know Kubernetes yet, then maybe don’t. But if you know it, it’s easy enough anyways, and if you see it growing beyond that, then there’s at least some sort of advantage of getting that set up. Now, whether it’s worth the time tradeoff, that’s up to the individual circumstances. But that makes a lot of sense.

Maybe a reverse version of this question might be not so much how small should you be, but how much do you need to learn? If you have just one node - sure, okay, great, but do you know about containers, do you know about this…? What are the components that you should know about or be willing to learn about to run Kubernetes?

Good question.

Yeah. By the way, I do wanna say that there are many users that are using one node, and by the way, on Google Cloud, one node is – we’ve just introduced the Developer tier, so getting a one node cluster actually doesn’t cost you anything.

Nice.

So you can set that up for free.

There’s a win.

Yeah, there’s a win! I think in terms of a learning curve, there are two things. If you are deploying a cluster by yourself on premise, there is a set of things you need to figure out how to deploy it. Depending on how you do the deployment, it can be very easy, or if you are doing something custom, it can take more time.

As far as using it, if you use it in a hosted environment or you’re not the one who’s actually doing the deployment of the cluster, I would say that it’s quite easy to use. You need to understand the concept of a service, which is going to be a part of your application, and you need to think about “Okay, how do I containerize my service?” But that’s something that you need to do if you’re gonna use Docker containers, so either way you’ll need to do that.

[59:50] Beyond that – I guess I’m biased, but the set of concepts in Kubernetes are fairly straightforward. It’s like “I’ve got my application, it’s made up of a few services. The services are going to run in pods, and I’m gonna write a set of declarative YAML that is gonna say how I want to run my service.” It’s really straightforward.

I agree. When I decided I was gonna move my family stuff over to a single node, a Kubernetes cluster, I spent a couple of days thinking about “How am I going to take this running VM image that I had from years ago and decompose it into containers in a way that made sense for me to manage it?” But I didn’t actually have to go that far. I could have just taken everything and jammed it together into one container and call it done, but I spent a couple days and I ended up with a pretty neat design where I’ve got a MySQL container, and I’ve got a PHP container that runs a little PHP site that we have, and I wrote a little container for Webtrees, which runs some genealogy software… I put them all together, and now when I wanna know what’s happening on my server, I have the same command line tool that I have available at work, and if I wanna update it, it’s really just one single command line; there’s no more SSH-ing and edit config files, it’s a different way of working that I think works really well.

That’s interesting too, because anybody who’s ever run Wordpress knows that if you use MySQL, then that often can be the thing that falls down whenever your site gets a ton of traffic, so it’s often somebody sees the page that says “Can’t connect to the MySQL server, or something like that”, so having that in some container and then obviously having that autoscale up or down or restart if it fails - or respond if it fails - totally makes sense to have that kind of architecture.

Exactly.

While it’s overkill, it makes sense. Technically, it’s not overkill.

Right, I get away with a very small VM and a very small MySQL container, but if for some reason lots of people wanted to start looking at my family genealogy, then I would move it to a bigger VM on its own and none of the frontend containers would even care.

Let’s talk about getting started then. We’ve talked quite a bit about how it works, the architecture, which, again, great example of it, because we followed, and listeners, again, if you didn’t go and check out the diagram, you should. But let’s talk about getting started - what’s the best way to get started? Is it a Git pull? How does this work?

Well, I think Aparna and I are a little biased, but I think the easiest way to get started is to get a Google Cloud account and go to Google Container Engine and with about six clicks you have a Kubernetes cluster up and running that you can use, the command line tools that you can download as part of our cloud SDK… You don’t need to look at the code, you don’t need to git checkout anything, you don’t need to compile in order to use the thing.

That’s the same environment that you get there that Pokémon’s using, and I think this is far and away the simplest way to do things. Now, in exchange for managed services, you give up some amount of control, so if you feel like you wanna dig into it more, you wanna go under the covers, you can just git checkout the current tree and you can run one of the scripts that’s in our repository called Kube-up, and the default target there is Google Container Engine, but there’s equivalents for other environments. Or you can go to a doc… Kelsey Hightower wrote this wonderful doc called Kubernetes The Hard Way where he takes apart all of the things that our scripts do and lays them out for people to follow step by step by step, and you can take that and you can apply it to whatever environment you wanna run it in.

Yeah, I think the best way to get started is on the container engine, and I think I already mentioned the one node free tier, but the other way - maybe you were about to say this, Tim - is Minikube.

Exactly. Minikube is our local development environment, so you can run a mock cluster on your laptop and you get the same command line tools, the same API server… Literally all the same code that’s running, but it runs on your laptop and presents you a virtual cluster.

That tutorial you mentioned from Kelsey was actually talked quite a bit about on GoTime episode #20, so if you’re listening to this and you wanna dive deep into some of the behind the scenes on that, Kelsey was on that show that day and kind of covered that, and lots of other fun stuff around Kubernetes, because he’s obviously a huge fan. It’s called “Kubernetes The Hard Way’”, it’s on GitHub; we’ll link it up in the show notes.

[01:04:11.29] Moving on from Getting Started – is that what we wanna cover there, or is there a bit more on the Getting Started part? I’ve got a link out to Minikube as well… Which is so funny that it’s Kube [kewb] there, but it’s not Kube [koob], Minikube [minikoob]. [laughter]

We’re stuck on it.

Yeah… You mentioned this as community-run. So this is a Google thing, son of Borg, so to speak, but there is community behind it. How does community transcend the Google-esque stuff of this? Having Google fund it, back it, support it… How does community play into this?

Well, it started as a Google thing. Initially we gave it the seed engineers and the seed ideas, but we had heavy engagement from guys like Red Hat very early in the process, and that’s been really instrumental to the project. The project from the day it was launched was intended to be governed by a non-Google body, so we donated the whole thing to the Cloud Native Compute Foundation, which was created to foster technologies like Kubernetes to bring the cloud-native world to fruition.

So Google does not own Kubernetes; Google still has a lot of people working on Kubernetes, but we do not own it, and we don’t get to unilaterally decide what happens to it. Instead, we have a community, we have a group of special interest groups that own different areas of the system: networking, storage, federation, scheduling… And they make decisions sort of independently with respect to their technical areas, and the whole thing is community-centric. We don’t make decisions without talking to the community, and net as of right now, I think Google is less than 45% of the net contributions.

Wow. We actually might have something in the future around the Cloud Native Computing Foundation. We work closely with parts of the Linux Foundation, so we’ve got an opportunity to talk a bit about that… And it’s interesting to see that Kubernetes is a part of that.

Yeah.

Yeah, we’re excited to be joined by lots of other projects there, like Prometheus and Rocket and ContainerD, that are really embracing the idea of this cloud-native world, where things are dynamic and the idea that you know concretely what everything is doing at any moment in time sort of fades away, and the system runs itself.

It’s also interesting to see that you care enough - or you’re diplomatic enough; that might be a better word - to hand this over to essentially the community, in that sense of the world. Being a Linux Foundation sub-thing with the Cloud Compute Foundation, it shows that Google wants to play a role but not own.

I think this is part of the ubiquity argument, too. We had to do this. If this remained a Google thing forever, there would be a lot of mistrust. Google has something of a track record for changing directions mid-stream, and we wanted people to be comfortable knowing that they can bet their business on this and that even if Google did walk away from it, that the thing still exists and has a life of its own. I’d say that part of it has been fantastically successful.

We’re the number one contributor, but we’re not the majority. In fact, the number two main contributor on the pie chart is unaffiliated or independent. So yeah, I think this was just a requirement of being in this space at this time in the industry.

[01:07:49.15] Yeah, I would say this is not all altruistic, right? We actually believe that in order to reach our audience - again, the audience is all the users on premise and across clouds - being open source is extremely important for that, and developing a community that works with users on premise in bare metal, across the world, is instrumental. The way that we developed the product is not just from Google, it’s through the community that is working actively with the users, and often it’s with the users themselves. [unintelligible 01:08:25.28] is a great example, eBay is a great example, New York Times… These are all users that also contribute back to the project; that makes the product stronger. That’s not altruism on the part of Google, I think that’s strategic.

I like that your perspective is about trust, which is super important, obviously, to put the thing that runs your thing – you need to have that full-out, 100% trust, be 110% trust… That’s an interesting perspective.

This is a good place to leave it. This was a great show - history, how it works, architecture… We couldn’t have asked for more to come out of this show, so thank you Aparna and Tim for joining us today. Any final closing thoughts before we close this show out?

Kubernetes is an open system. I always end every talk I do with the same slide - we’re open, we’re an open community, we wanna hear from people. If you have an idea, don’t think that you can’t bring it to us. Please come and share with us what problems you’re trying to solve and we’ll see what we can do.

That’s awesome. Thank you again so much for joining us today… It was an awesome show. Thank!

Thanks, guys.

Our transcripts are open source on GitHub. Improvements are welcome. 💚