Alex Sims, a Senior Software Engineer at James & James, an eCommerce fulfilment company, reached out to us about the Kaizen story of the third-party logistics (3PL) platform that he has been involved with for several years now.

The system delivered 16 millions of orders in 10 years, and 4.5 million in the last year alone. All the numbers are going up, and there is only so much that a single PHP monolith deployed as VM images can handle. So how do you even start thinking about the architectural improvements, and inspire everyone involved to move towards better?

We encourage you to look at the architectural diagrams in the show notes, especially the 10 year roadmap, and ask Alex for a blog post follow-up. While today’s episode was a good conversation starter, there is a lot that we did not have time to cover.

Featuring

Sponsors

Sourcegraph – Move fast, even in big codebases. Sourcegraph is universal code search for every developer and team. Easily search across all the code that matters to you and your organization: find example code, explore and read code, debug issues, and more. Head to info.sourcegraph.com/changelog and click the button “Try Sourcegraph now” to get started.

Raygun – Never miss another mission-critical issue again — Raygun Alerting is now available for Crash Reporting and Real User Monitoring, to make sure you are quickly notified of the errors, crashes, and front-end performance issues that matter most to you and your business. Set thresholds for your alert based on an increase in error count, a spike in load time, or new issues introduced in the latest deployment. Start your free 14-day trial at Raygun.com

OpenZiti by NetFoundry – Programmable network overlay and associated edge components for application-embedded, zero-trust networking. Check it out at netfoundry.io/changelog

Chronosphere – Chronosphere is the observability platform for cloud-native teams operating at scale. When it comes to observability, teams need a reliable, scalable, and efficient solution so they can know about issues well before their customers do. Teams choose Chronosphere to help them move faster than the competition. Learn more and get a demo at chronosphere.io.

Notes & Links

- James & James - eCommerce Fulfilment Services

Transcript

Play the audio to listen along while you enjoy the transcript. 🎧

I was very excited when Alex reached out to me, telling me how inspirational some of the Kaizen episodes were for him, and how he tried applying that principle of improving a little every day, and working towards something better. And after a couple of months, he told me that that worked really well, so I wanted to find out more. So we have Alex here today to share with us that Kaizen story. Welcome, Alex.

It’s great to be here. I’ve really been enjoying listening to Ship It over the past few months, since you launched it… And one of the things I’ve really found interesting at the start is just how many tools in this space that you can cover, and I’ve really been trying to apply some of those at the company level, at James & James.

Just to give a little bit of context and background around who I am and what I do - my name is Alex, I work for a company called James & James, which is a 4PL business. We essentially control every part of the supply chain for our customers. So we will own the integration with multiple selling stores, like Amazon, eBay, we’ll pull all your orders in and we will pick, pack them, send them out, and also handle the returns process for any customers that want their orders back.

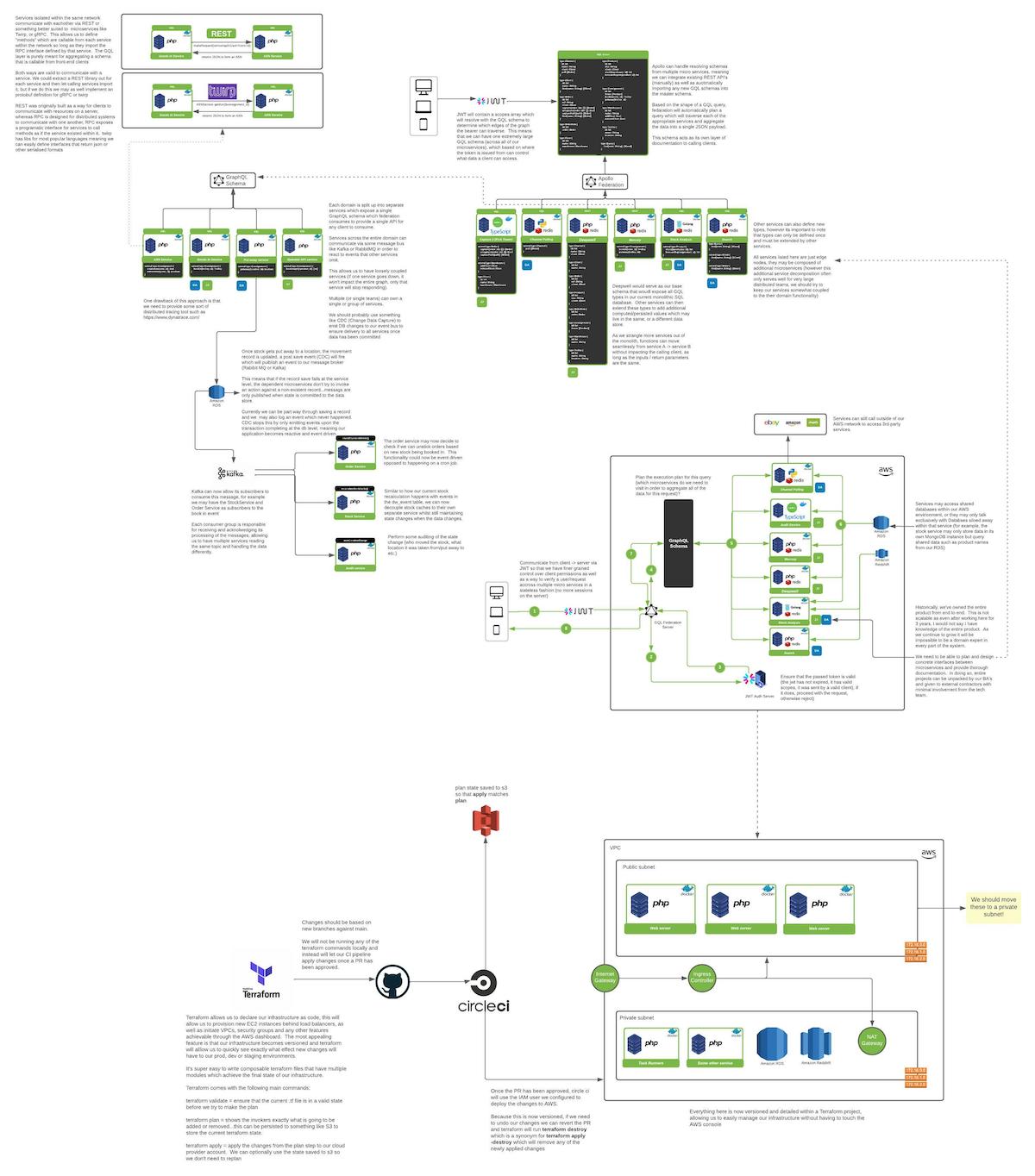

[04:24] As you can imagine, there’s quite a lot that goes on behind the scenes, lots of moving parts, and lots of systems that currently exist in a legacy application. One of the things that we’ve been trying to do, at least over the last past year, is think about how we can break away from that monolithic application and start making the right incisions to pull certain services out into (I’d like to say) a microservices architecture, but I don’t know if we need to fully drive one. Instead, I’d like to think of us as a service-oriented architecture, where we have certain boundaries of the business extrapolated to services, that augment the core of the business.

So one thing which really struck me, Alex, is that you’re new to the company, and new to the industry as well, and I’m very curious how was the starting point for you… Because some of us have been doing this for 10, 15, 20 years, and we no longer have that fresh perspective, that fresh pair of eyes. There’s always like knowledge built on top of knowledge, on top of knowledge, and I think it’s different. But for you, that joined this industry - was it a year ago, two years ago?

So I’ve been with the company now for about 4,5 years. The company has been around since 2010, and was originally written in Symfony 1.4; it’s an old PHP application… And there’s some really long-standing developers on the team. We’ve got some who have been here for over 10 years, some have only been here for the last 5 or 6… So I would say I’m more of one of the senior developers within the team… But coming in from university and having all these bright ideas, and most people I’ve graduated with went on to do greenfield projects; I went into James & James because I was excited about the business domain and the challenges that it was solving… But what came with that was legacy tech and sort of having to adjust my perspective and outlook on how you build applications.

So going in, I’d been very used to TDD, and realizing that wasn’t a thing that was really done, because that version of the framework had a really awkward pipeline for writing tests, and there was just really nothing there to give new developers examples of what to do. We sort of went along and built software in a very waterfall way at the start. We used to have very long two-week cycles where we would then bundle up all of the code changes, which may be hundreds of files and thousands and thousands of lines of code… And every other Thursday we’d look at them, put a big PR together. All of the team, five developers, would test it, we’d sign off on a Friday - don’t deploy on a Friday, because you don’t wanna get called on the weekend - and then Monday morning, as long as we were happy with our smoke tests, we’d deploy.

And that worked… It worked fine for a few years. Two years, I think. And it was only really when the pandemic hit, or maybe just before the pandemic hit, we’d started to shift to a more distributed team, and working from home a lot more… And that same release cadence didn’t work for us anymore. We needed to change, and we hired an agile consultant and worked alongside him for a while. And after doing our first 3-4 sprints, it was really clear, the feedback we were getting… Deploying multiple changes a day, or a week, and realizing you’re not having to test every edge of production before you’re satisfied; the confidence of your build was great. I’m not sure if you wanna interject, or if you have another question.

[08:14] If this was a game, I would say that you start on the Hard mode. So like Easy, Medium, Hard - this was definitely Hard, because you went into a legacy project, which by the way, doesn’t mean a bad thing; it just means a lot of assumptions, a lot of learnings that you were not part of… And you have the end result of those learnings, and you have to make it work in a way that may have worked great in the first 4-5 years, but then things started changing. And you’re right, once the pandemic hit, everything changed, for everyone.

So trying to understand how all these complicated systems, or even if there’s one, how they interconnect and how they work, and why you do things in a certain way - that had to be rethought, because all of a sudden a lot more people are ordering things online… I’m sure the volume went up for you in those two years, so you were doing a lot more business… And that was putting certain pressures in terms of confidence, in terms of reliability… A lot more was riding on those two weeks of changes, and a disruption would have been far more significant for the company. So getting it right - there was a pressure to get it right.

So I’m very curious, how did that transition work for you, from shipping every two weeks, to I imagine shipping more often?

I think I’ll rewind the clock a little bit, back to when I first started again, 4-5 years ago.

Sure.

When I first started, we were still small enough that we could host pretty much everything on one machine… I think we even had a shared database server on that machine.

Let me guess, FTP? Or rsync?

Yeah, I mean, back in the early days it was definitely some tinkering in prod, but we had a deployment pipeline, at least, when I joined.

That was using FTP. [laughs]

[laughs] No, we’ve been using DeployHQ ever since I’ve been there, and it’s worked great. But I think that [unintelligible 00:10:11.01] I’d have to check our pipeline, but I’m pretty sure that’s how it works. But yeah, I’ve rewound the clock, didn’t I? So I rewound the clock back to like 2017, when we were on one server, and every year we’d sort of come to the November/December part of the year, and that’s our peak; that’s when our volume goes through the roof, as you can imagine. You’ve got Black Friday coming up, you’ve got Christmas coming up, and everyone is placing orders. And that’s really when we start to stress-test our system. You start looking at the amount of actions that are sitting in the queue, are we falling behind, how many have processed in the last ten minutes… And we’ve got alerts set up that if any of those queues start looking like we’re gonna fall into a half an hour or greater backlog, we start sending messages to Slack to say “Hey, look at this - it’s time to spin up some new workers, so we can start clearing that queue.”

That generally has been quite interesting, because when I first started, it was like “Everything’s on fire, all hands on deck”, developers get in there, we’re spinning up servers from AMIs, or whatever the alternative was in Rackspace; just some image that we’ve provisioned. Put in new ones into the pools… And then once we’ve cleared the backlog and we’re looking like we’re settled, we would manually then tear those boxes down, take them out of the pool… And that worked great for years. But as you can imagine, it’s reacting when you need to react. And over the last couple of years, every time we’ve got to peak, because we’ve been focusing for over a year on trying to harden the system, so find anywhere where there’s really slow queries and optimize those, find any of the pages where it’s being greedy and running a query for every single object that you’re trying to get, rather than hydrating everything in one go - we’ve optimized all of those, and then when we come around to peak, we’re seeing that we’re not having to do as much of this firefighting.

[12:08] And the really good thing for us was because we’d had two or three peaks of aggressive growth, by the time we got to the pandemic, we actually found the opposite of what we thought was gonna happen… The system just – it stood up and it managed to get through. Of course, there were additional features that the fulfillment center needed to process the backlog of orders, but in terms of system stability everything held up, and that was really exciting to see, from our perspective.

Okay. So at what point did you go from a single server to multiple servers? Did that happen, by the way?

It did. I think it was within a few months after I joined the company; we split the database off onto a second server, and then I think we finally had – I think we’d always had web servers, and then worker servers that processed all of the tasks. But I think when I joined, shortly after in that first peak, was when we started adding more and more of those nodes to the pool.

Okay. And were you using something like Chef, or Puppet, or TerraForm? What did you have at the time to maybe - not automate this, but at least make it easier.

Everything was done, like, “Get Shelly into the console and spinning everything up.” I know back in 2018 (I think) we at least started using Ansible to provision users on these servers. And we still use that system today to provision users on servers.

Okay. These are the users – like, the developers that maybe SSH, or the system administrators…

Yes. Sort of recently I dockerized our applications, so that developers have an opportunity to work locally, if they want to.

Right. That is a big step. Did you say recently? How recent was this, by the way?

I wrote it probably about 8-9 months ago, and that was two applications. And then set up a bunch of stuff locally, with Traefik, so you’d get a reverse proxy. With named, local DNS to point to it. It works really nice.

But then everybody else that doesn’t wanna work locally, maybe the machine can’t run it - we have a remote environment; we have a user space for everybody, and then just access the application through some DNS.

That makes sense. Okay. Is there like a single remote environment that everyone uses, or…?

Yes.

A single environment. Okay. And don’t you find that people maybe trip over each other’s feet?

No, because in that environment – I think we’ve got some sort of wildcard certificate, maybe. So we have like developer initials, dot, and then the name of the application. So all requests go through your user space to your instance of the application.

Interesting. Okay. And when it comes to the database – like, do they provision database which is like just for their application? How does that work? How does the data work. There’s always issues with the data. There’s the data gravity.

Yeah. So we use a pascalian version of a backup, and then developers work off that. And it kind of works, but the thing that’s really awkward with it is now that we’ve actually – so to remind again, a little bit, one of the contractors that we’ve just brought on, he has written support for the PHP unit in this legacy Symfony 1.4 application. So we’ve started to introduce unit tests to that… The problem being because we work off a backup, it’s really heavy if you then wanna try and run tests against that, because the data is always changing, you can’t be certain for state… So what we’re doing now is inside the Docker application adding a MariaDB container that comes empty, and then we run the build script from the schema, to provision the database so we can start running tests against it. We haven’t yet got any seeds, because as you can imagine in a legacy application with a legacy monolithic database, we have hundreds of tables, and we can’t easily create seed data for you at this point. So we’re trying to sort of change the way we think about our tests, and just make the tests seed the data they care about, so we can start seeing some green flags.

[16:21] I really like this real-world challenge, because it’s real, so first of all, this thing is happening, it’s been there for many years… And you have to figure out a way of improving it, little by little, while not breaking workflows that have been there for years, that people depend on and they trust, and they know that it will work. So in this sea of technology and workflows and people, what would you say was the biggest challenge?

I think this is really interesting, because this brings me onto one of the biggest rewrites that we’ve probably done, at least in the time that I’ve been at the company… And it was probably our most critical piece of business logic. Essentially, when I want to get a set of orders given to me as a picker in the warehouse, I wanna find the most efficient pick route, and the most similar orders that I can get on that pick route to fill up my trolley. Now, we had a legacy process that would manage this for years, and myself and another developer that I work with were tasked with rewriting it, because it was slow. It was slow to the order of sometimes it would take up to a minute and a half to get a list of orders back, and they weren’t always closest in proximity, or you had dissimilar orders on a trolley, so when the packer got it, they’d be less efficient because they wouldn’t know “What packaging do I use for this order, or do I use for that order?”

So this project landed on our desk, and we looked at “What can we rewrite in?” We’d been talking about services for a while… This seems like a good opportunity to make a service for this. And I think this also sort of highlighted my naivety as a new developer coming out of university… I was like, “Right, I’m gonna go pick the latest PHP framework that I can…” Because I was so bounded to PHP at this point. We were a PHP house, and outside of it we weren’t looking at other languages. We wanted everyone on the team to be able to understand it… So it was “Pick a PHP framework.” And I went with Lumen at the time, because it had some really good benchmarks for API-driven applications, and this was gonna be a purely API-driven service. So I selected Lumen, and then got the base application spun up… I was like, “Great. We can see the Hello World root. Let’s start putting code into it.” And we looked up the logic for capture, and it was like “Oh, there’s thousands and thousands of lines. So before we can even do anything, we have to pour over all of the lines, pull them apart, because there’s not single responsibility for every method.” So we tried to extrapolate those into sensible names, and put unit tests behind everything… And it was working great. We managed to pull over everything in 2-3 months, to get it ported and tested. But then we had to implement the new algorithms over the top to make it more efficient. So we applied those, probably another 2-3 months later, up to the point where we got to our peak deadline of “Yeah, we need to switch to solve the peak because it’s gonna be the thing that gets us through.” As you can imagine, running that close to the deadline and knowing you’re operating in your most busy time of year - it’s “How do I have the confidence now to switch this where we don’t have the space to deal with potentially” not an operational disaster, because we were confident it would still work… But we were not 100% confident in that feature.

So we left it off peak, we did some testing after, and what we ended up doing was spinning up another node in production… And I guess you could sort of say it was a canary release, because it’s this one server that’s running in production, that’s running on a specific branch… And that portion of users started having all of their requests for capture directed through to the new API. Fortunately, we actually had a really good response from it. I think we got the time down to anywhere between 5 and 10 seconds.

[20:14] Yeah, that’s a huge improvement… At least like an order of magnitude faster. When you have a 10x, you can feel it.

Yeah. It felt great going out into the warehouse and not seeing loads of people standing around and waiting to capture… Because as you’re capturing the next person can’t capture, because it’s a mutually exclusive log with all orders on a specific level, and you don’t wanna over-subscribe stock to more than one operator at a time. So because of that, it could be huge bottlenecks in the past, which we’ve sort of now eradicated a lot. So it felt really good.

But what happened over time is because we don’t really have anyone in the role that I’m in now, which is more of a solutions architect, that boundary sort of got blurred… And it was like “Oh, let’s start writing a new service that we can pull in”, and instead of really thinking about what that boundary is and what goes into that Lumen application, we just started writing more code there… And after a while I just sort of stepped back and thought “We’re actually building another monolith as we’re breaking away from the monolith.” And although it feels like the right choice now, three years down the line we’re gonna say “Now we’ve got two monoliths.” And what do you do at that point, right? You’ve now got two legacy applications that you need to upgrade to the latest version, but if you’re not spending time upgrading those versions, you’re gonna have a big, big headache and a lot of technical debt.

Yeah…

So from what I’m hearing, it was the domain and how to break down the domain into these discrete units, that was the most challenging part… Because you had a real operation that you could not affect; the impact of getting it wrong and the risk of getting it wrong was very high… So you were mitigating that via this canary to inform you whether “Is this going in the right direction?” So I imagine that you were routing part of the traffic through that, just to see how it would behave…

Yes.

…and it behaved well, at like a small-scale traffic. So I understand how that drove you into this role of a more like a solutions architect, which you’re missing that high-level perspective, so someone has to fill that void, so that it unblocks a bunch of things… So did that work out the way you were expecting it to work out, you stepping in this role and having that high-level perspective?

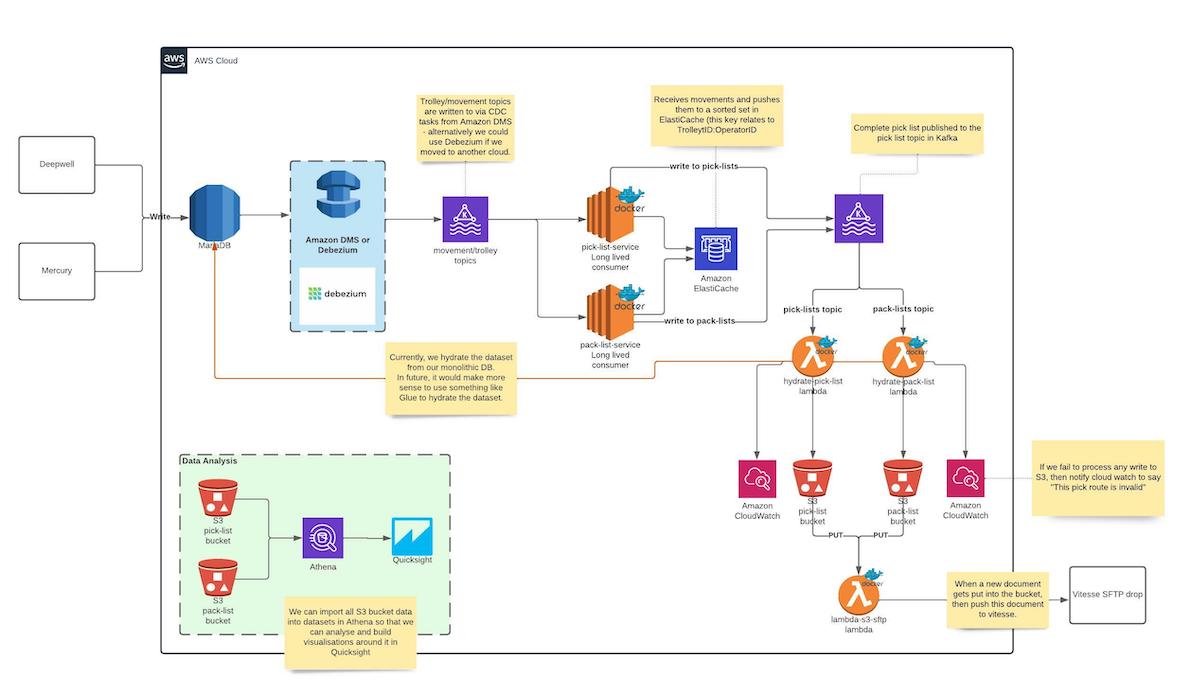

[24:17] So in this new role - I’ve only been doing it for the last six months… But the value that I really wanted to gain from it is look at some of the upcoming problems that we’ve got and think “Do we really need to put this into the monolith, or can we start thinking about how we break this out of the monolith and put it into its own service?” And one of the things that we’ve worked on recently is we wanna get a better idea of the productivity of our warehouses. And every single thing that happens inside of our operation records something called a movement, and a movement represents either stock into the warehouse, an internal transfer between locations, or an outbound transfer, say, to an order, and then out to a customer.

What we could have done is added events inside of our Symfony 1.4 application, and process those processed those in that application [unintelligible 00:25:11.28] and push them out to a third-party that we’re using to do some analysis. What we’ve done instead is introduce a Kafka layer where every single movement that happens in the warehouse gets replayed to Kafka through something called CDC. And then once it’s in Kafka, as many applications as you want can consume those movements, and then reason with them however they want, hydrate it into a different dataset, and that’s what we’re currently feeding off to our third-party provider. I’ve actually got a diagram. I wouldn’t mind –

Yes, we’ll put it in the show notes. Yeah, that sounds great.

I think it’ll help illustrate that point.

Okay. So there were these architectural changes that needed to happen, but you were also mentioning quite a bit about confidence… And I’m wondering, how are you getting confidence in all these changes to know whether you’re going in the right direction? To know whether the system keeps remaining stable, responsive… How are you tracking that so that you know whether you’re going in the right direction?

So in the last year maybe – I don’t know if he’s been here with us for 18 months yet, but sort of in that range we’ve had two QAs join the team. They’re definitely doing a great job using something called Robot to write an automated test pack for our legacy application. So any defects that we find at the point of doing our development testing, they get rolled up into testing, in that automated test pack. Obviously, we then try to write as many unit tests as possible in development, especially in the Lumen application, to give us confidence in what we’re shipping at the backend level. That’s been going really well. So at the point of deployment we verify that those tests are all going green, and if they are, we merge to main. But in our legacy application, as I mentioned earlier, the unit tests are sort of a new addition, and there’s only a small handful of them, so we’re really relying on what the Robot Framework is driving to give us confidence in what we’re shipping.

There’s also still that whole manual phase, where we do have the QAs do some manual smoke testing before we release new features… And any major features that touch core aspects of the business we will put onto a beta node, and direct a small portion of traffic to that node. And that seems to work pretty well for us.

So when it comes to understanding what happens in production, knowing when certain responses are slow, or they’re failing, or knowing when for example a deployment failed - do you track those things at all?

Yeah. Ever since I’ve been at the company we’ve used Datadog. Only over the last 12 months have we become more advanced users. We’ve installed APM so we can get some really nice insights to how PHP is behaving, and also we can see everything that the database is able to see where slow queries are, because our optimizing is needed. And it’s so useful to see - someone in the warehouse might report “Oh, this pager is going slow”, and you go look at the APM and you can see exactly what requests are going slow, what was sent, what may have caused it, what correlates with your findings, and see if it’s actually a problem in the code, or is it one of the nodes going slow, and it needs a restart, or something…

[28:29] I think I’ve mentioned to you we’re thinking about moving to Kubernetes in the future, but right now we’re still six or seven web nodes behind a load balancer, running on EC2, with a similar amount of task nodes running on EC2. We still have to manually apply patches and restart those boxes occasionally, and there’s still some manual work there.

Okay. So after my conversation with Kelsey - that was episode 44 - the first question which I asked was not about automation, but about documentation. And it’s something –

I knew you’d ask this… [laughs]

…top of my mind. So how well-documented is your process, in terms of deployments, in terms of what runs where, how to do things…?

I would say we’re not as good as we could be, but we’ve made a good start. I was listening to the podcast of Kelsey the other day, and I thought - he spoke some really good points here, because it completely discredited what I just proposed to the team; the whole thing of “Can you prove in principle first? Give me the human instructions of how I would provision this myself”, which is what we currently have. We have a documentation and a wiki to say “If I want to go and create a new server to run this application, here’s the list of the packages that you need, here’s all of the correct permissions that you need”, and that’s actually what I used to then go write the Dockerfile for the application.

But what I then said to the team was “I don’t think we need this documentation anymore. I think the Dockerfile is living proof of the documentation.” But it’s the wrong way to think about it. And that really resonated with me and I started going back to “You need both.” I think it’s healthy to have both.

Yeah. So definitely, the documentation is your source of truth, for sure… And then any automation that you add on top of that – and this is something which I myself am changing my approach. Because I was always “Automate, automate, automate”, but not enough “Document.” Because I was thinking, “Well, the automation is the documentation.” Isn’t it? Apparently not… And I can definitely see that, because I was catching myself having to rewrite these huge things, and I’d rewrite them by looking at the automation, which is the wrong way to go about it.

So if you have good documentation, it’s very easy to write the new automation, without looking at what you had previously, because you will make those jumps every now and then. And if you don’t have documentation - well, good luck figuring out your Chef, or your Puppet, or your makefile, or whatever you may have; your scripts, or whatever the case may be. And by the way, there’s no right or wrong. It’s like TerraForm, whatever. All things work for your context, because otherwise you wouldn’t be using them, I suppose. Right?

Yeah, exactly. [laughs]

So that’s the test… Like, “Does it work for you? Great. So then you’re using the right thing.” It’s really interesting that you bring up Kubernetes, because that would be my first - or it used to be my first go-to. “Just use Kubernetes.” And in some cases - and you kind of feel it when “Okay, I think we may need this container orchestrator, and scheduler, and scaling up and scaling down…” But there’s a lot of knowledge that you need to have. And that’s why I say, my perspective is having a bunch of years of experience using it. But your perspective is this thing isn’t new. I don’t know how will this fail. And we’ve been doing this for like ten years now, four or five years on my watch, and we’ve been fine. So replacing that with something so fundamentally different is a very big proposal, right? Like, how do you even approach this? I’m glad that you have documentation. [laughs]

[31:56] Yeah. It’s also the thing that worries me, because obviously, we’ve been doing this for ten years now, we’ve been absolutely fine provisioning images, spinning up more nodes and [unintelligible 00:32:06.20] as we need. Scaling down with demand… Obviously, Amazon has got auto-scaling groups and things that we could leverage to get a lot of that out of them. But one of the problems that I see is if we truly start going towards a service-oriented architecture where we have more than even just the current two applications that we have now, as you add a third or a fourth service, the waters start to get muddied. How would you replicate this environment somewhere else? And especially in the context of Docker, how can I run this locally? And actually getting up and running. If I have everything in Kubernetes to say “I just wanna start this cluster, and here’s how you start all the services, and just go, and it’s all automated”, someone could just pick it up and run a script and it’s all done. But if you don’t have that layer, it becomes a lot harder to migrate.

However, that being said, one of the interesting things that I’ve sort of been learning as I’ve transitioned into this role is every decision you make comes with a cost, whether that be a cost to actually do the migration, or a cost to maintain what you’ve migrated; you need to say “If we do Kubernetes, it’s gonna offer these advantages in the future, but it’s gonna come at the cost of maybe hiring someone to actually set it up for us in the first place and do some training. It’s also gonna cost up-skilling ops engineers to understand it. Whereas if we carry on as we are, the risk is the cost of migration is now six months, instead of a month or four weeks to move.” What benefits the business, and what gets the results that you need? And it’s hard to answer that question sometimes.

Yeah. And I think that’s why when you’re on a trajectory of improvement and your focus is “How do we get better at this?”, whatever “this” means, it’s so contextual, because you instinctively know which small step gives you the biggest win. And then you take that step. And it doesn’t matter how you label it, whether it’s Kubernetes or something else; is this the smallest investment of effort that yields the highest benefits, and has maybe the lowest trade-offs?

Exactly.

And by the way, some of those things aren’t as black and white, and they’re not obvious, but you have to try it, and then you kind of say “Okay, this kind of feels right”, and it’s your experience, it’s your gut instinct, it has to do with the people that you work with, some of them will know things that you don’t… And I think that’s really fascinating, how people come together, or don’t, when it comes to solving those problems. Because when you have teams that work together, and each of you shares their unique perspective, amazing things happen. So how do you encourage your team to do that, so that you together are taking the steps in the right direction, and you don’t have one of you pulling towards Kubernetes, someone else pulling towards for example Knative, or “Let’s go serverless”, someone else saying “No, no, no. We’ll have this – it’s Zend. Have you heard of Zend? It’s amazing! It’s going to revolutionize the world, the Zend framework.” I remember that PHP framework… That was a very interesting one. And there was CodeIgniter, something like that…

Yeah, I remember that.

I had my fair share of like I think two years with PHP frameworks, and then I discovered Ruby on Rails. So that’s what happened. And that was like 15 years ago, or 10 years ago, however long. But still, the point being that there’s all these frameworks that we use, there’s all these tools that we use, but the focus is the people. It’s the processes, it’s the things that enable us to get on with work, with the least amount of frustration. We need to enjoy it. If we’re not enjoying this, what are we even doing? Being miserable?

[35:52] You have to enjoy your day-to-day to get the most out of yourself… And not even just yourself, but your team. And one of the things that I learned over the last few years from someone that came on going “Everything needs to be shining. We need to be using this technology, and this technology.” And coming into a team with (I’d say) more seasoned developers, that have sort of weathered the storm of the shiny, and sort of said “We’ve got this tech. It’s done us solid for five years (at that point). We don’t necessarily need to upgrade.” As long as we’re following the upgrade path to sort of say “I’m on PHP five point something, and it’s now end-of-life, and I’m now bumping up to the next version, to make sure that we haven’t got any vulnerabilities at the language level.” Then I think we’re doing the right thing and we can carry on pushing ahead with it.

There needs to be a real reason to break away from doing something the way that you’re doing, in order to justify that cost of adding that extra complexity to the stack… Because every time – like, now we’re out of service. We’re adding additional complexity that someone needs to understand. If I were to walk away, who else on the team can pick that up and understand it?

And one of the important parts in my role now is everything that we’re building is being thoroughly documented. From the perspective of architectural diagrams this is how different parts of the system interact with one another, this is the contract that this service has exposed to the rest of these services… Once you understand that part, everything else just becomes black box. And if I were to walk away, then someone should be able to come in, reference the documentation and go “Okay, I can see how we push messages to this service now. This is the flow.”

Back to your original point on how do you get other people excited and make them want to learn the new things - I think that’s a hard one. Like I said earlier, when I came in I was trying to hard-sell React, and “We need to use Laravel, we need to get rid of Symfony 1.4.” Coming in and just saying those things without really being able to say “This is why” was a really hard sell. But over time, we’ve seen that maintaining Symfony 1.4 is hard, especially when we jumped from PHP 5 to PHP 7.2 [unintelligible 00:38:08.08] on GitHub, and they have been maintaining that Symfony 1.4 fork for years, and upgrading it with every major version of PHP and minor version of PHP that comes out. But that’s only gonna happen for so long. If anyone decides to stop maintaining that, then we’re in hot water when PHP 7 goes end of life and we go to 8. I think we’re already looking at how we can start moving to 8, and then fortunately I believe that fork is still maintaining that version. But yeah, there comes a point where you have to pull off the plaster and start thinking about how do you move to something that’s gonna be sustainable.

How has your perspective changed when it comes to chasing the shiny, chasing the one which is popular?

Yeah, I still do a lot of additional work outside of work. I definitely think I’m a bit of a tech evangelist; I’m always trying new tools. But I think after being a developer for seven years, everyone’s solving the same problems, just with a nicer bit of syntactic sugar around it… And over time you sort of realize these things are nice, and they can do some additional cool things; but are they doing it to an order of magnitude better than what you’re currently using? And if the answer is no, then there’s big alarm bells of “Do I want to integrate this into a project that’s mature, and that nobody is gonna understand that it’s gonna come with a training cost?” A lot of the time the answer is no.

What I tend to look at now with the new services that I’ve built recently, it was - PHP is really good for serving web requests and sort of doing some messaging stuff, but we’ve not got a really high throughput service that needs to be a long-lived consumer of messages, and then processing those messages… And I thought, “Well, Node.js off the bat is screaming out at me”, because it’s built for handling lots of messages at once, and processing them. And once I started doing that PHP prototype of the same service, I think it took me two or three days to make the same progress that I’d made with Node in a day. And I think that sort of just harks back to using the right tool for the job.

[40:20] Yeah.

I’m sure someone’s gonna be listening and thinking “No, PHP can definitely do that really easily.” But then that was maybe a gap in my knowledge, and I knew Node better, and nobody on the team had the experience of “Oh, how do you process Kafka messages with PHP?” It’s like, “Oh, okay. I know how to use this, and here’s a concept. Here’s how it works. I’ve proved it works. Let’s put it into production.”

If I rewind a little bit more, that’s my [unintelligible 00:40:47.00] black box, is if you scoped your services narrowly enough, as long as I’m conforming to that contract, if someone comes along and says “No, actually we can use PHP to process Kafka, and we’ll still get a similar or the same throughput, and it makes more sense, because the rest of the team - it’s their primary language.” If your service is narrowly scoped, you can rewrite that service in PHP, scrap and burn the new Node.js one, and just drop the PHP one as a replacement. That’s where having those architectural diagrams I think really helps people come in and sort of understand “If I was to rebuild this in PHP, and get rid of the Node variant, this is what I’d need to do.”

Is this code someone in the open, available for people to see?

Currently, we’re closed source. I don’t know if we’ll ever go open source, or if it’s something we’ll consider. That’s something I have to check. But currently no.

Okay. So the reason I ask whether the code is in the open - and by the way, it can have a closed source license, but still be available - is that’s where you get people being able to look at it, and maybe offer suggestions. I mean, I’m not going to sell you on the benefits of open source, because I’m sure you know them already… But if there is a way that you can share the problems that you have in a way that maybe helps others, I imagine that others would return the favor, in that you may be doing something and they say “You know what - this is cool. I’m going to help, because this is cool.” And it helps on so many fronts. So that’s one point.

The other point which I was thinking about was when it comes to changing the paradigm that you currently have. So you have applications, you have frameworks, maybe microservices… But what about something like serverless, where you have these functions where you get to model your business logic in ways that the whole platform and the whole ecosystem supports it. And I’m not sure whether serverless - again, I wouldn’t choose it just for this reason, but doing certain things… You mentioned you tried Node.js; if you try the same thing with some serverless primitives, how far do you get where you have eventing out of the box, you have serving out of the box? …you know, these concepts that are higher-level concepts, and building things is easier, because you don’t have to worry “Well, which PHP version am I using? Which framework am I using?” That doesn’t exist. You have the components that you wire together, and the components are messaging primitives, or serving primitives, rather than this class or this function.

Exactly. [unintelligible 00:43:21.11] legacy applications. Everything gets written to our primary MariaDB node. We’ve got a couple of replicas of this, but that’s not too important. Amazon DMS is the CDC piece, which will then replay any of the [unintelligible 00:43:35.26] tables that we subscribe to to Kafka, and then we’ve got our long-lived Docker consumers running on the EC2 instance, and they do some synchronization with Redis, running on ElastiCache, which will tell us when a pick list starts and when a pick list ends. And then at the point of an end of it happening, it will publish to another topic in Kafka.

[43:58] Right.

You were just talking about the serverless part, and [unintelligible 00:44:00.00] some lambda functions to actually do the hydration of that data, and then save those to an S3 bucket, which then invokes another lambda function and publishes it to our partner, which does our analysis on that data. We then ingest all of that S3 data into Athena, so we can visualize and query it in QuickSight to do some dashboards of this stream data that we’re building. And that’s how that all comes together; I hope it makes a bit more sense now.

It does, actually. So is this something that you have now, or something that you’re working towards?

No, we’ve switched it on a month and a half ago, and it has run without any issues, within thousands and thousands of pick lists. And one really cool thing is last night – or no, the night before last we applied some security patches to the EC2 box, and had forgot to restart the Docker container, so we got a message from our partner in the morning saying “We’ve not received any data from you in the last ten hours.” It’s like, “Whoa… Okay, what’s going on?” And restarted the Docker container, and there was no gaps, there was no data loss. It just replayed all the messages, start to finish, and we published every file that was amiss. And I was like, “This is exactly where I’ve been wanting to work toward…”

Amazing.

…having fault-tolerant, failover self-healing services. It was great.

That to me sounds like a resilient system, that was built-in from the start… So when failure does happen - because guess what, it will; and if you think it won’t - well, I don’t think you’ve been doing it long enough to know that, to have not experienced that… So how are you going to build this resilience in? The CDNs fail. They do. It happens maybe once every five years, but they do fail. Systems that you think will never fail - they will, eventually. And okay, they may happen infrequently, and you may not need to design for that, or build for that. But if it does fail, what is the worst thing that can happen, or what is your plan? Like, the data gets wiped. Are you going to not have backups, because you think data will never get wiped?

So have something, and think about that… Because - like in your case, it was a very simple thing, like a security patch, and things were not restarted. We make mistakes all the time. And if your systems can’t tolerate any mistakes, then I think that’s the first step. Try and make a few mistakes. If I’m 100% uptime - well, you know what? I know, if you have a single server… I have, for example, servers which I’m using which have like 5-6 years of uptime, and that’s okay. But it can go down any time, and I’ll be fine. I don’t trust that it’ll never go down, and it doesn’t give me a warm feeling; every year it’s like “Okay, this thing will go down at some point. It’s closer and closer to the day that it goes down.”

Yeah, I had 5-6 years of uptime and then it went down.

There you go. It just happens. The longer you wait – I was gonna say, the longer the clock ticks, you’re going closer and closer to a downtime. And are you okay with that? You may be okay, but some systems can’t tolerate that, so how are you going to design your system to cope with that downtime when it eventually comes?

Exactly.

I’m very curious how does your deployment pipeline look like. And when I say “deployment pipeline” I don’t mean just the actual pipeline, but from committing code - what happens between the commit and the code going out in production?

Yeah, so right now I would say it’s still very basic. We sort of ensure our tests are passing as a predeployment phase. It’s not a part of a pipeline deployment. Once we deploy [unintelligible 00:49:24.18] bundles everything up and just pushes it out to the servers, and then we get notified in Slack that a new version has gone live, and then we do our smoke tests. So it’s still a very basic pipeline at the moment as for our main application.

One of the things we’re working towards is trying to get our robot framework to run before we do the deployment, because I think the way the QA engineer phrased it was “It’s like reading yesterday’s newspaper today”, because we will run the automated framework after the deployment has happened, because it takes so long. And we want that immediate feedback in production if something’s gone out and we’re able to use it and we don’t wanna be blocked for 20-30 minutes.

So that’s still really basic… However, some of the newer services that we’ve got are slightly more complicated. They’re not massively complicated pipelines. Our lambda ones - it will grab the source, run it through a compile phase in a makefile, run the tests against it… If that succeeds, it builds the final image, and then pushes our artifact to the image registry, and then that gets deployed to our lambda.

How does that get deployed to lambda, or what deploys it to lambda?

Jenkins. We’ve got a Jenkins pipeline there.

So does the Jenkins pipeline also run the image building, and the testing, and all that?

Yes, it does everything, yeah.

And does the code go to GitHub, or somewhere else?

Yes, everything goes to GitHub, and then at the point of merging to main, that’s when the pipelines get triggered.

Okay. So you don’t trigger pipelines on branches.

Not currently. I think that’s something we’d want to do. Running tests against branches just to ensure that before we merge we’re fully confident, both from a “I’m the developer. I’m happy”, but also “Yeah, you’ve definitely not missed anything from the tests.” That’s where I wanna get to.

One thing I’ve got set up locally - I use Husky to basically run my own pipeline before I push every commit, so I can commit as much as I want locally. But at the point of pushing - like, in our Node project it will compile TypeScript and then it will run over unit tests, and if anything’s failing, it’ll prevent me from pushing. Same with PHP. If I try to push and something’s broken, it’s gonna scream at me and say “No, you can’t do that.” But that’s currently an optional workflow that our developers can opt into.

Right. Do you use GitHub Actions, by any chance?

Not yet. It’s something I’ve been exploring in side projects. I’ve also been exploring the Codespaces a bit, but we’re not there [unintelligible 00:51:52.21] yet.

So Jenkins, I’m assuming it’s polling the GitHub repository. So you have a Jenkins… Where is that running? I’m just curious.

I think we might just have a server that’s running that. I’ll have to check with our ops guy.

Yeah? So on EC2, because I know that you’re running on AWS… You mentioned that a couple of times, all the lambda stuff, so it’s all AWS. Do you use anything else other than AWS?

[52:18] We still have – we’ve migrated almost everything now from Rackspace. We’ve been with them for years. We have one application running over there. It’s just a really basic React application which we can probably actually put into S3. It makes more sense. And then we’ve moved all of our assets over too. That was a challenge in itself, migrating about 2.5 terabytes of assets from Rackspace to AWS in a weekend. That was an interesting move.

I think that in itself is like another episode, or at least like a blog post worth reading, because that sounds amazing. I remember us touching up on that last time when we spoke.

I think we did.

Okay, yeah. Did I ask about the blog post, if you have one, at the time?

Yeah, we haven’t yet. I mean, with everything going on right now… It’s a bit crazy.

Yeah, of course.

I’ve been wanting to start a blog, but that’s down the road a little bit. I’ve got two posts I wanna talk about, one being the migration piece and one being the screenshot I’ve shared with you.

Yeah. I’ll make sure to – if you can share it, I’ll make sure to put it in the show notes.

Of course. That sounds like – I really like it, by the way. If listeners listened to us talking about the diagram - when it’s in the show notes, it makes sense to look at it as you talk about it. But it looks – like, a lot of the time I’m just looking at the shape of things and most of the times I know if the shape looks right, whether it’s like some text, or whether it’s like a diagram… It’s little things, like for example arrows going in a single direction, arrows criss-crossing them… You know, like too much text, or too little text, or not enough of a certain type of text… It’s those sorts of things, heuristics which I apply to realize “Is this something interesting or not? Do I want to find out more about it?” And I definitely have to say, your diagram looked very interesting; just like from the basic shape of it, things were logical and it kind of made sense. I was curious to find out more about the various components. We’ll make sure to put it in the show notes.

So you push to GitHub, Jenkins pulls it down, runs all these things, and then it deploys to a bunch of targets, whether it’s S3, whether it’s an image registry, whether it’s maybe a server… I imagine it may be SSH-ing and performing things there… Again, I’m imagining, I’m guessing here. How often do you merge into main?

So from a legacy application, it depends on the time of year, and it depends what you’re working on. If we’ve broken a ticket down into multiple deliverables that can actually go out to production, we can merge several times a day. If we’ve got a larger project that’s gonna disrupt something - because we don’t currently have proper feature flagging. We have our own sort of flag system that we’ve built years and years ago. “If this is enabled, then show this page”, which kind of works… But [unintelligible 00:54:59.24] you get the feedback of “Hey, this switch has been hanging around for a while, and it hasn’t been turned on. You should probably remove it.” We don’t have that visibility, so we try to stick away from adding lots and lots of switches in the codebase.

So that’s my point - if we’re building a larger, disruptive feature, what we tend to do is accrue a trunk, and that trunk has main merged into it multiple times a week, and then we will deploy that as of when it’s ready.

So it totally depends on the scope of the change. Hotfixes and small improvements we can deliver multiple times a day. Larger projects may be on a bi-weekly cadence, or maybe a monthly cadence.

I see. Okay. And don’t you find when you deploy less often that things tend to go wrong?

Yes, definitely. Every time we deploy something that’s larger in scope I think we put a lot more eyes on it; we’ll sort of hark back to waterfall days of “Everyone jump on board, and we’ll open a spreadsheet and we’ll record defects” and then realize “Oh, they’re existing defects”, but some of them may be nearly introduced… And it takes a lot longer to deploy. The friction between the whole team in getting something into main is a lot higher… Whereas when we can just release little and often, if there is an issue, 1) it’s easier to say “Oh, it could be this change”, and 2) it’s easier to roll things back without removing loads of new features that are perfectly fine from the operational stuff and our clients.

[56:31] Yeah, that makes sense, and it definitely – I’m gonna say it confirms my bias, but I think there is at least a half-truth there, because that’s my experience as well. When you deploy more frequently small changes, it’s much easier to basically check yourself and then check whether you’re going the right direction, see the things that you may have missed because it’s so easy to miss them, and you will absolutely miss them… So how do you build a process in which you can push small changes constantly, ship small changes constantly, and verify that it works. Or if it doesn’t work - okay, let me know, what didn’t work?

So when it comes to future improvements, what are you thinking in the next 3-6 months? What are the big-ticket items that you would like to spend time on improving?

So I would really like to see us actually using at least Docker in production. We’ve been talking about it for a while, we haven’t made the leap to it yet… One thing that we wanna do to really prove that Docker can give us some reward in production is to start using it for [unintelligible 00:57:32.05] environments, to sort of say “Hey stakeholder, here’s the feature you’ve requested at this URL”, and everything’s already in Docker. And at the point that we’re happy to close it, happy to say “Let’s now merge to main”, that gets torn down. I would love a pipeline where as soon as a PR leaves draft status, it automatically spins up a Docker container in the cloud, [unintelligible 00:57:55.28] 53, gives it a nice URL, and then we can paste that over to our stakeholders. And at the point of merging, then it tears everything down automatically. I think that would be fantastic. That’s where I’d really like us to get to.

Hm… I may just have something for you.

[laughs]

Let’s talk about this, because this is really interesting. So many people that I talk to want exactly this - a really simple thing, which is exactly like you described. Some documentation, please, and some common understand of how this thing works… But what you’ve described I think is 80% what the majority that I talk to want when it comes to previews. Just give me a URL; it’s my app, it’s my code… It’s easier to do if you use services like for example Netlify, or Vercel, or something like that, where you can have preview environments very easily. If you’re using a PaaS, it also helps a lot, like Fly. And that was one thing which I wanted to do, but obviously we wound up doing something else… You know, like the plan versus reality; what you want versus what happens.

Yeah…

But I still think there’s a lot of value in having that, in that every branch gets a preview environment, and in this case it’s not a static website; it’s a bit more complicated, so how do you set it up and you tear it down? I’m sure things like these exist, but I haven’t seen one that works well yet. Again, I may not have looked very hard and very far… It is something which I definitely want to work with other people to solve, because I can see the value of it. So yeah, let’s talk about that some more.

Yeah, this is great.

What would you say is the most important takeaway from our conversation, as we’re wrapping up?

Yeah, so I think for me it would be if you’re working on a monolithic application and you’re struggling to see the light of where you wanna break away and start doing something new, it’d be to - every change request that comes through, sort of try and identify “Is this the one where we could think about experimenting, or at least releasing maybe two in parallel that do the same thing? Is it small enough that I can get another service out there that delivers exactly what I want?”

At the start for us it was a large upfront cost, but now every new service we’re putting out there has a small operational cost. Because as soon as you get that layer in place that lets you push messages, that happening in your legacy database to other services - I’d say it gives us super-powers; we can now really start thinking about building whatever we want off of our old legacy data as it’s getting played through the system.

Alex, I’m really excited about your journey. Thank you very much for sharing it with us. I’m very curious to see how you continue and what happens next. By the sound of it, you have all the right ingredients, where you’re going in the right direction, you’re discovering the right things, and you seem to have a great team that supports you and want to help you get there. And that makes a huge difference, if you have buy-in from those that you work with. So that’s great.

Well, thank you very much for joining us today. This has been great, and I’m looking forward to having you again when you’re at like your next milestone. I’m really excited for that.

Thanks for having me. I look forward to the next one.

Our transcripts are open source on GitHub. Improvements are welcome. 💚