In today’s episode, we talk about distroless, ko, apko, melange, musl and glibc. The context is Wolfi OS, a community Linux OS designed for the container and cloud-native era. If you are looking for the lightest possible container base image with 0 CVEs and both glibc and musl support, Wolfi OS & the related chainguard-images are worth checking out.

Ariadne Conill is an Alpine Linux TSC member & Software Engineer at Chainguard.

Featuring

Sponsors

Sentry – Working code means happy customers. That’s exactly why teams choose Sentry. From error tracking to performance monitoring, Sentry helps teams see what actually matters, resolve problems quicker, and learn continuously about their applications - from the frontend to the backend. Use the code CHANGELOG and get the team plan free for three months.

FireHydrant – The reliability platform for every developer. Incidents impact everyone, not just SREs. FireHydrant gives teams the tools to maintain service catalogs, respond to incidents, communicate through status pages, and learn with retrospectives. Small teams up to 10 people can get started for free with all FireHydrant features included. No credit card required to sign up. Learn more at firehydrant.com/

Sourcegraph – Transform your code into a queryable database to create customizable visual dashboards in seconds. Sourcegraph recently launched Code Insights — now you can track what really matters to you and your team in your codebase. See how other teams are using this awesome feature at about.sourcegraph.com/code-insights

Notes & Links

- Ariadne’s Twitter thread that kick-started this episode

- Wolfi OS - a stripped-down distro designed for the cloud-native era

- Minimal Container images from Chainguard

- ko - build and deploy Go applications on Kubernetes

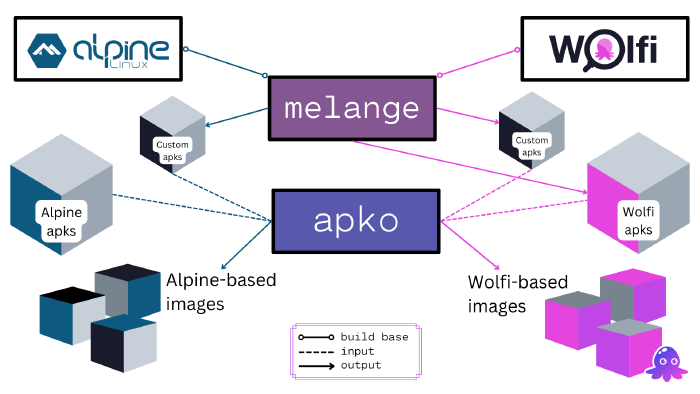

- apko Overview - build OCI images using APK directly

- melange - build APKs from source code

- musl libc

- glibc - GNU C library

- “We discovered a bug in our repository management service”

Chapters

| Chapter Number | Chapter Start Time | Chapter Title | Chapter Duration |

| 1 | 00:00 | Welcome | 01:00 |

| 2 | 01:00 | Sponsor: Sentry | 00:40 |

| 3 | 01:40 | Intro | 05:13 |

| 4 | 06:54 | Apk vs Apko | 04:38 |

| 5 | 11:32 | Building with Apk | 03:21 |

| 6 | 14:53 | Apko and Ko | 05:23 |

| 7 | 20:16 | Sponsor: FireHydrant | 01:18 |

| 8 | 21:34 | Wolfi OS in Chainguard | 04:33 |

| 9 | 26:07 | Musl and Glibc | 06:06 |

| 10 | 32:13 | DNS | 02:11 |

| 11 | 34:24 | Musl Developement team | 00:48 |

| 12 | 35:12 | Chainguard kernel | 02:28 |

| 13 | 37:40 | Do you like rust? | 04:59 |

| 14 | 42:39 | Rust in Linux | 02:02 |

| 15 | 44:41 | Sponsor: Sourcegraph | 02:22 |

| 16 | 47:04 | Witchery | 04:29 |

| 17 | 51:33 | Host opperating system | 02:13 |

| 18 | 53:45 | The bug | 02:13 |

| 19 | 55:59 | Publishing images | 03:01 |

| 20 | 59:00 | Platform support for ??? | 01:02 |

| 21 | 1:00:02 | KubeCon | 01:37 |

| 22 | 1:01:39 | Wrap up | 00:42 |

| 23 | 1:02:20 | Outro | 00:48 |

Transcript

Play the audio to listen along while you enjoy the transcript. 🎧

So Ariadne, what depths of depravity would you go to in order to avoid maintaining a project using the Bazel build system?

Well, in this case, I made an entire distribution to avoid building anything with Bazel. The background, of course, is at Chainguard we were supporting two different types of approach to distroless… And the original one, Google Cloud Platform distroless was based on Bazel basically. There are custom rules to take a .deb file and extract it, and all of the dependency management is done by hand. There’s like manually solved dependency trees that are expressed as Bazel rules, and basically GCP distroless is a huge mess to maintain… So we were looking for various options to replace that mess.

Back in June, I built a prototype, kind of like apko, called Debco. The idea is that we would use mmdebstrap which is kind of a improved version of Debootstrap, which is what the Debian Installer uses to install Debian. The idea is that we would use the mmdebstrap, which is basically the same thing, but built on top of apt. And that gives us all of the dependency solving and everything. But what we’ve found is that if you’re not solving these dependency issues by hand and just extracting the debs, basically we couldn’t get any sort of solution out of mmdebstrap that was remotely similar to what distroless was already shipping.

So that was a huge problem for us, because that meant that we were going to be stuck with Bazel, or we were going to have to basically do the same thing the Bazel system was doing, but manually specify the dependency solutions by hand… And we didn’t really want to go that way, because like apko - it just uses apk to solve everything. And at that time, if you were using Alpine-based images, you could get this really nice distroless solution, and it was simple, and it was easy… You didn’t have to mess with Bazel, or anything. So we wanted to bring that to the GNU Linux world.

Ultimately, what I did is I started building a prototype distribution that became Wolfi. First, I did like a stage one cross-compile toolchain as a package repository, built it with Melange, took that to management, and it was just like, “Look, we could just build our own GNU Linux distribution that gives us exactly what we need.” After some conversations, we went with that idea, instead of, you know, messing with Debian… Because Debian is not really designed for what the distroless community needs.

What does the distroless community need?

[05:32] So the distroless community is looking to build minimal container images… Basically, only the things that are necessary to support the user’s application, and nothing else. So if you have like a statically-linked Go binary, you might just wind up with the binary itself, and then like etcresolve.conf and a couple of other files like that; just enough to make it work. So what distroless is about as enabling all of those different use cases to make images where it’s just the app, and only the things necessary to support the app. And what we’ve built is a better solution for that, because right now if you have like an app in a language like Python, and you need more than what the basic distroless Python image requires, you have to go learn Bazel to customize the image. So Wolfi lets you do all of that with apko. And it’s nice, and clean, and easy by comparison. No need to use Bazel, or anything like that.

Right. So the apk package manager - that comes from Alpine. How is that different from apko? What is the difference between apl and apko.

So apk is a package manager. It originally was started by Alpine. There’s been multiple versions of apk over the years. The first one was a bunch of shell scripts, and it kind of operated on something similar to like Solaris; you know, UNIX System V tarball packages. The second generation largely inspired by apt and Pacman; also Canary, in terms of user experience… And it’s used by multiple distributions now. It’s used by Alpine, it’s used by one named Gamera,it’s used by one named Adélie and now also Wolfi. And there are a few others that I have neglected to mention, mostly because I’ve just forgotten the names of them, because they’re small.

Yeah. How do you know all those Linux distributions? I’ve never heard of those. How come you know them?

I’m one of the maintainers of apk, so…

Right. That explains it.

So I deal with those distributions all the time. And notably, OpenWRT is preparing to switch to apk from their own package manager, because…

Interesting.

…they don’t want to maintain it anymore.

So small enough to fit in a router operating system, the OpenWRT. Very nice. Okay, that’s interesting.

So by comparison, apko is a tool that we developed at Chainguard. And what it does is it writes apk and uses apk to generate an OCI image. So you can have like a YAML file that says “I want these packages, from these repositories, signed with these keys.” It’ll go out and it’ll set all of that up, and it will build the image, and it’ll include all of those

various configuration files behind, so that you can then take a scanner and see what is actually in the image. And that’s a really big thing, because a lot of people who make small images, they use from scratch in a Docker file, and then they copy everything over. And if you do that, then your security scanning doesn’t detect anything. And that makes it a nightmare for your security team, because they have no idea what’s in these images. They don’t know how to remediate anything. They don’t know what to tell their developers to fix. So it’s very important that everything in an image is cataloged somehow.

[10:08] Basically, the thing about apko is that everything that goes into an image generated by apko has to be an apk package. And as a result, everything is catalogued in some way. So that brings us to SBOMs, the software bill of materials. That’s kind of the same mantra applied to all of container images at large, all of IoT, all of like industrial computing. And basically, the idea is that all software needs to be catalogued, and these catalogs need to be in standard formats, and all of that. So basically, the deal about apko is that it makes all of that really easy. And in fact, apko can generate an SBOM for you, based on inspecting the data that apk leaves behind when it generates the image. So that’s the difference between the two tools. One is the package manager, and the other is the thing that wraps the package manager, builds images, builds SBOMs, and all of that.

I know that you have a vast experience building packages for Linux distributions. Year 2000 you started with Audacious, like wanting it to be packaged the right way for both Debian and Ubuntu. Now, fast-forward to apk, because that is, I think, the package manager that you have the most experience with… How difficult is it to build a package in apk, or using for apk, versus a deb package?

Night and day.

Right. Okay. Which is night, which is day?

So the Debian build system is basically - you have a Debian directory, and then there’s a file in there named rules. And that is a makefile. And you have to spell out all of the steps needed to build a .deb file, using that rules file. There are things like Debhelper, but it’s not like they’re an integrated build system; it’s a huge mess that you have to deal with.

In apk there are multiple build systems that you can choose from. There is the classical abuild, which is used by Alpine and Adélie. It is much simpler than the Debian way; it uses a shell script called an apkbuild. There’s some variables in there that describe what the package is, and then there are some steps that it goes through to actually build the package, and that’s it. Really clean, self-contained… You can go to get.alpinelinux.org/aports and see a whole bunch of apk builds.

Wolfi uses a system called Melange, which - it takes kind of the same approach, but instead of being a shell script, we have YAML. And because we have YAML, we can do all sorts of structured data stuff, like tracking individual files and their copyright information, we can express more types of relationships between things…

The other thing about it that’s different than an apk build is it’s oriented around pipelines. So you define one or more pipeline, the main pipeline runs first, and then you have sub packages, which have their own pipelines, which can mutate the other packages to do whatever it’s needed to split them up. And it’s built on this pipeline concept…

[14:13] So if you are familiar with like GitHub Actions or something like that, then you’re pretty much ready to go with Melange. It’s basically the same concept, except instead of it being GitHub Actions, you’re building a package. But if you understand one, it’s easy to understand the other.

Right. And the package definition - this is the apk package that you’ll get at the end; you declare it as YAML, that Melange understands, interprets, runs, and then it spits out an apk package. Is that how it works?

Yeah.

Okay. Cool. So there’s Melange, there’s apko… But there’s also ko. What is the difference between apko and ko.

So ko is much older than apko. It was a tool that was developed by Google; it was originally part of Knative. Basically, the idea is that if you have a Go project, you can run ko against it, and it will build an image that contains just enough to run the Go application. So ko kind of is like a layer above apko in that regard, because - apko, you get a flat, single-layer image out, and then ko will take an image like that and then put a Go application on top of it as a separate layer. Originally, ko would build packages using the GCP distroless static image. But recently, it has changed to the Chainguard static image, which is maintained by Chainguard, obviously. And that image contains only the things necessary to support a statically-linked Go application. So ko generates a statically-linked Go application, runs it on top of Chainguard’s static image, and then the combination of these two gives you an OCI image that you could then go deploy in Kubernetes, or Docker, or whatever you need.

The reason why it was created was because the Knative people also had to deal with Bazel. They didn’t want to deal with Bazel, so they made ko, which does exactly what they need, without Bazel. And eventually, Knative, Kubernetes, and even Istio switched away from using Bazel to use their own customized build systems. And that is, you know, the thing.

So those images, the Chainguard Images that you build - that is something new. How is Wolfi OS related to the Chainguard Images?

So Chainguard Images are basically our take on how GCP distroless should evolve. And we use apko to do the final assembly of all of the Chainguard images. They run nightly, which means that all of the updates are constantly being applied… So basically, what Chainguard Images is, is a really cool tech demo for apko that you can use in production as a practical set of base images.

So it’s like Python, Go, NGINX… There’s quite a few examples there, and they’re growing since I looked at them a month ago, when this first came out, roughly; about a month ago. Do you intend to add others? Is this community-driven, user-driven…? How does that work?

[18:08] It’s a community-driven project, but also we have customers for Chainguard Images, which - in those cases, they’re paying us to support specific use cases. And obviously, Chainguard engineers are going to prioritize the specific use cases that are required by our customers, since, you know, they pay us.

Other than that, anybody who wants to jump in or needs a custom image can open a request for one in the Chainguard Images metabug tracker, and we triage that every week, internally, and we will try to make those things happen. I mean, as long as the request is reasonable, obviously. Some types of requests we might be like, “Well, we can’t really support that for free. Maybe you can contact our sales team.”

Do accept contributions?

We do. Everything under the Chainguard Images project is open source, in the true spirit of open source. There is no CLA you have to sign, or anything like that. You can just jump in and contribute. You retain your copyright even, at the moment; that might change in the future. I can’t promise anything, obviously. But we are trying to do everything in the full spirit of open source. There is a channel on the Kubernetes Slack, #apko, which - it’s not directly related to Chainguard Images, but we can discuss them there. And yeah, it’s basically a community project. Anybody who wants to be involved can just jump in and start contributing.

So coming back to my previous question, how does Wolfi OS relate to the Chainguard Images - I can see there’s a Wolfi base image, but I think the question still stands… Where does Wolfi OS fit in the Chainguard Images ecosystem?

We use Wolfi inside the Chainguard Images ecosystem when we want to provide a glibc-based image. Right now we’re using Alpine when we want to provide musl-based images, but that might change in the future as well, because there are advantages to just standardizing on Wolfi in general, an example being that Alpine and Wolfi version numbers are not necessarily the same… So if you scan a Wolfi image based on the Alpine security database, it could be a nightmare, and we don’t recommend doing that… But some people get confused and do it.

Another issue is people sometimes try to mix packages between Wolfi and Alpine. So by standardizing the ecosystem around Wolfi for both musl and glibc variants, we can kind of control that better. Basically, the takeaway is when we need glibc to support something, we use Wolfi. But we might use Wolfi more in the future for musl workloads as well.

So why is musl versus glibc a big deal? I have my own story to share, but I’m wondering from your perspective, why would you pick one versus the other?

Generally, we recommend using musl when you can, which is probably controversial to some listeners listening to this later on. The reason why is because musl prioritizes memory safety, it prioritizes the avoidance of side effects, it prioritizes the avoidance of undefined behavior. These are really important things for security.

The other thing is you can actually go and read the musl source code and follow it. Glibc has these things called indirect functions, which means that you can go into the glibc codebase, think that you’re looking at like the printf function, but then when you get to the actual printf function based on where you would think that it would be, you will find that it is actually a thunk to somewhere else. So you have to go on this journey through the glibc codebase to actually find out why you’re hitting a bug.

By comparison, if you go to look for the printf function in musl, it is right where you would expect it to be. There is no level of indirection there. Basically, musl is a lot simpler in terms of how it’s implemented, and because of that, the behavior is a lot more predictable. There’s a lot of features that are security-oriented, especially in musl 1.2. There’s a new malloc that is hardened against the user trying to mess with the state of malloc, which is an entire class of vulnerabilities.

Yeah, basically, the deal with musl is that people sometimes hit unexpected behavioral differences between musl and glibc, which does piss people off… But the reason why those differences exist is important. Usually, it’s because it’s difficult or possibly impossible to implement the functionality in a way that it’s provably secure without breaking compatibility with glibc. But many of our customers require the glibc compatibility, and so that’s why we created Wolfi.

[26:06] Yeah. So my story with musl and glibc is that in the many years that I was dealing with RabbitMQ in Erlang, or should I say Erlang in the context of RabbitMQ, is that RabbitMQ would sometimes just lock up, or the memory would not be reclaimed correctly… Like, some very weird memory-related functionality that was deep down in the kernel. And I say kernel, but it actually proved out to be musl; it was like the Alpine-based images. And then, one decision that we took a couple of years back, we said, “We don’t support musl, we support glibc, because the behavior especially around memory is more predictable” and IO just behaved better. And that is an anecdotal observation. We didn’t go too deep in the implementation to see how IO differs in musl versus glibc. But the memory one was just like enough to say, “No, no, we’re not opening that box.” So I’m wondering how much of the maybe – I don’t want say legacy systems, but the systems that have been around for 15, 20+ years, they can behave differently on musl, which is much newer than glibc. And as you mentioned, the implementation is different, too. So there’s potentially a bunch of edge cases that on musl are yet to be discovered… Maybe. I don’t know.

So I look at it the other way. I think that, instead of thinking about musl as being the problem, you should think about - in this case it would be the Beam virtual machine, or maybe some part of Erling that has actually got the problem… Because musl is designed to where it operates very strictly by what is actually in the specification.

So the most common thing that happens with musl is that the developer is unaware of something in the specification, and then they run into friction with musl, because… For example, perhaps they are not properly locking mutexes between threads, and they’ll malloc something on one thread, and then they’ll free it from another thread. Musl will frequently fail in that case, because the spec says that that is undefined behavior.

Arguably, it is dangerous for programs to continue running when they hit undefined behavior. Now, that doesn’t mean that programs should lock up. In general, in musl, when we detect that a program has done something that isn’t allowed by the spec, we call a special function called a_crash, which is supposed to make the compiler insert an undefined opcode into the assembly, and that is supposed to make the program crash right at the point where the undefined behavior was encountered. Sometimes that’s not the case, where we can’t actually prove that undefined behavior occurred, and so that’s when you run into these cases where the program will lock up, or you might have a memory leak, or something like that. But usually, in these cases, that’s because we have found ourselves in a gray area, and we don’t know how to proceed in a safe way, so we choose the least bad option available to us. Sometimes that’s not what the developer wants, but the point is, if you’re hitting weird behavior with musl, it’s probably because you’re doing something that is either outright banned in POSIX, or it is under-specified in POSIX, and our interpretation tends to lean conservative… So we prefer to not continue from that point. So basically, in my opinion, musl gets blamed a lot, when in reality it’s trying to show you that something’s wrong.

[30:36] I think that’s a great test, and it’s a great indicator to dig further. So, like, there is likely a problem here. And as you mentioned, because things are undefined in the spec.

But at the same time, I can understand why customers and end users of Alpine get frustrated, and they’re like, “I don’t want to deal with this. Glibc works.”

That’s it. That was my moment 3-4 years ago. I said like, you know, glibc works. How about we sidestep this problem, rather than solve it? I mean, we don’t have to solve every single problem; sometimes is best to sidestep, for the benefit of everyone involved, and then come back to it. And I think, in a way, that’s what’s happening now. I mean, I wish I was maybe closer involved with the Beam VM, just to understand where this thing is happening… But if someone’s listening, and if someone’s interested, dig into it.

But the takeaway is Wolfi OS doesn’t make a choice. It lets users choose whether they want glibc or musl based on their needs. You’d recommend musl, for all the reasons that you mentioned, but glibc is a possibility, unlike Alpine, where you can’t choose.

Yeah. And I just want to stress… If your program is doing something weird under musl, based on anecdotal evidence, 9 times out of 10 that has turned into a CVE. So you should definitely not blow it off. Like, it means something is wrong, most of the time… Except when it comes to DNS, but we’re working on fixing that.

[laughs] Alright… What’s the story with the DNS? Tell me about it.

So DNS is really hard to do if you want to prove that an implementation is memory-safe. The only way that we’ve found to do it originally was to constrain our DNS responses that we hand back to the application to the original 512-byte limit. But now we have things like Kubernetes with core DNS, and we have DKIM. And we have all of these arguably broken DNS servers out there that don’t return nothing on UDP, even though that’s not allowed by the DNS spec… And then if you query them by a TCP, then you get the real answer. So what we’re doing now is we are adding TCP support to musl, but we’re still going to respect the 512 byte limit in terms of what we return back to the application. So that means that if there’s some crazy person out there that wants to return back like 200 IPs from a DNS query, that’s probably not going to work in musl still, but it does mean that if you’re dealing with these DNS servers that only support DNS over TCP, or they only support DNS over TCP, if the UDP responsibility truncated, what we’re doing is we’re changing it so that we can handle those cases… But we will also handle the truncation for you, so that we can handle giving you a small, memory-safe response, but also deal with these incompatible DNS over TCP-only servers out there. And that’s something that Chainguard has been sponsoring in musl.

[34:22] Okay. So when you say “we”, it implies that you’re part of the musl development team, is that right?

I am a contributor to musl. There’s only one person that has commit access to the canonical musl tree, and that is Rich Felker. But I have many patches in musl. I’ve worked on many function implementations in musl such as fopencookie, and a few others over the years. So yeah… I also maintain a lot of the add-ons, like glib viewContext, and so on.

Interesting. Okay, so we started talking about Chainguard Images, and then we ended up here. Great detour, I really enjoyed it. Now, what is the kernel that the Chainguard images are using?

So when you use a Chainguard image, it’s a container image. So your container environment provides the kernel services. And that’s why Wolfi doesn’t presently ship a kernel, because right now we’re targeting specifically the container use case. But down the road, we’re planning to target other use cases, such as IoT, and bare metal. And in those cases, there will be kernels. But those kernels will be provided as separate layers on top of the Wolfi core OS… Which is a really powerful concept, and that’s why our marketing people decided it’s an undistribution… Because since it’s modular in nature, you have room for a lot more opinions. Like, we have a customer who wants systemd, but we have other customers that don’t. We can put systemd into its own layer, and as a result, if you want systemd, you can opt into having systemd. But if you don’t want systemd, then you don’t have to have it.

The nice thing about that is that both types of use cases are satisfied; you know, the people who want systemd can have it, and the people who don’t, don’t have it. And it’s the same way with the kernel. It’s the same way with drivers, and everything else. In the embedded world there are these things called board support packages. And what we’ve basically done is brought that concept to an aspirationally mainline distribution. And we think it’s a powerful concept, because it enables there to be a lot of room for differing opinions on how things should be done, while the community at large benefits. We’ll see how that turns out, obviously, but right now we are enthusiastic that what we’re doing is an interesting path to be on, and what we’re enabling here provides actual value over the traditional monorepo approach that distributions take.

Right. Do you like Rust, the programming language?

Well, there are certainly pros and cons to using it.

Are you a fan? Would you describe yourself as a fan, or indifferent?

[37:51] I am a fan of certain things about it. I’m not a fan of the people who go around and they say, “Oh, we have to rewrite everything in Rust.” I think that that is not very helpful. I think that a better approach for Rust advocacy would be to implement competing software, instead of going and encouraging rewrites in Rust… And let the community decide what provides the best solution.

On the other hand, there’s a lot about Rust that is really good. The fact that you can define a model and code against that model, and then prove that the model is correct. Rust mostly uses this functionality for memory safety, but you can use it for other things… And that makes it really helpful for writing things like emulators, or drivers, or various state machines, anything like that. So to me, it’s obvious why Rust would be a good fit for like the Linux kernel.

But then I don’t like the fact that the compile times take forever. I don’t like the fact that there is only one de facto implementation of Rust that’s complete. I don’t like the fact that there are people in the Rust community that are skeptical towards standardization of Rust… I think that Rust is a great programming language to use for writing code that you want to prove certain aspects of, be it memory safety, or correctness, or whatever… But there are those in the community that I feel are harmful towards Rust adoption, because instead of talking about things that would make it more practical to adopt Rust in the real world, they talk about why we shouldn’t have standardization, and how having standardization might apply braking energy to the forward momentum of the project. And there might be some truth to that, but I think also having standards in Rust would be more helpful in terms of adoption, more helpful in terms of advocacy of the language…

You know, one of the big complaints about Rust originally was, okay, you write something in Rust, and then a year later, you have to rewrite it again, because they changed half the language. These days, that’s not so much the case anymore. But if you don’t have standardization, you can’t really fight back against that particular piece of FUD. So to me, basically, Rust – the Rust community doesn’t know what they want. Some people want Rust to become a mature programming language, some people want it to still have the level of freedom and be a sandbox of like an emergent language. And you can’t have both. Like, at some point, you have to decide, “Are we going to push towards maturity or not?” And I think until the Rust community has that conversation, it’s going to be hard for them to convince a lot of people who are still in the C world that Rust is ready for them to take seriously.

I know a lot of people who write C. Nobody really enjoys writing C. Nobody wakes up and says, “Oh man, I really love using malloc, and free, and making sure I get everything right.” But the thing is, until there is a push for maturity in the language ecosystem, and standardization in the language ecosystem, there’s going to be enough doubt in the community of system programmers that use C that they’re not going to jump on board. And a lot of those people who aren’t jumping on board really want to, but they want to see some sort of commitment towards standardization before they do it. Because the thing about C is C is really boring.

[42:27] Some would say that’s a necessity for infrastructure. You want boring for infrastructure. Things that you need to depend on must be boring, I would say. So what are your thoughts on Rust shipping in the Linux Kernel?

Well, for me right now, the worst case is that it’s an annoyance. The best case is that, because now the Linux Kernel is using it, there’s no choice but to talk about standardization. Also, because Linux is using Rust, or Linux is going to be using Rust, that enables a lot of possibilities in terms of, you know, this model-driven development for writing drivers. Like, we see that with Asahi. They modeled out how the GPU drivers should work, and now they are coding against that model to create an actual Linux Kernel driver. And that is a really powerful thing. Because when you go all-in with that approach to writing programs of Rust - they call it “correct by construction” - you can build programs much faster, because you can have the confidence that what you’re doing is right.

So overall, I’m optimistic, but at the same time, do I see Rust being used in like the variations of the Linux kernel that Alpine ships in the next 6 to 12 months? Probably not. Because right now we’re still working on ensuring that Rust is production-ready in Alpine. And until we are confident that it is, we’re not going to have the kernel depend on it.

Right. Okay, that makes sense.

Have you written some Rust? I’ve been doing a bit of research and I think it came up Witchery… Did Witchery by any chance use Rust at some point?

So the prototype at apko, and Melange, and all of that came from a project called Witchery. The original Witchery is actually written in shell scripting, but we did build a prototype in Rust for a lot of the functionality. When I went to Chainguard, because it became obvious that there was a lot of overlap in what I was doing and what Chainguard was doing, I decided to rewrite it all in Go… Because Chainguard had a lot of Go developers, and by rewriting it all in Go, that enabled me to use them all as resources. I mean, that’s not a nice way of saying it, but you know what I mean.

So I could have continued maintaining it all in Rust, and it would have been fine. But the goal was to ensure that other people inside Chainguard could work on it easily. And since Chainguard was primarily a Go shop, it made sense to just rewrite it all.

At some point, I will probably open source the original Rust version. But the original Rust version is a lot different than what we’re shipping today. So my fear in doing that is that if we ship the Rust version, then people might get confused and complain that it doesn’t work right, and all of that.

One thing which I find very interesting about Witchery is the names that you have chosen. So before apko it was Witchery Compose; and before Melange, it was Witchery BuildPack. Why did you chose those particular names, Witchery Compose and Witchery BuildPack?

So Witchery Compose composed the packages into an OCI image, and it used Docker to do it, and it was a mess. But the reason why I called it Witchery Compose is because it composed. And the reason why I called it Witchery BuildPack is because it took pre-existing code that you already built, or if you built it with like BuildKit or something, and it generated an apk package. Like, that’s all it did.

There was a lot that we learned from that process, and we ultimately abandoned that version of Witchery, because it didn’t really get us to where we wanted to be. Like, one of the key things that we heard from possible customers was that they didn’t want to depend on Docker. And so as a result of not wanting to depend on Docker, we built what ultimately became apko. And what we also found out is that actually, the thing that people hate the most about Docker is building software with Docker.

Interesting…

[laughs] So we built what became Melange. And the funny thing is, Melange was actually called Melange before I came to Chainguard. Apko was still Witchery Compose. And the Rust project that’s sitting on my computer is called like Witchery Compose 2, or something terrible like that.

Basically, the reason why we call called it Melange is because if you’re taking apks and you’re building apks into an image, then Melange is the spice of life. That’s literally what it means in French. So packages are the spice of life, therefore Melange.

That’s a good one. I didn’t realize that. Very nice. Okay. So we have all these artifacts, we have SBOMs, we have very nice supply chain security just built into these build tools, it just happens… I’m wondering what do you have on the other side? So what is the host operating system that you would pick to run these containers? And then how do you ensure that the containers that you run are secure? What would you pick?

[51:58] So that’s kind of how Witchery and Chainguard kind of collided with each other… Because Chainguard – Chainguard started working on the other part of it; they started it with a product that is now called Chainguard Enforce. It is a thing that you can plug into Kubernetes, that verifies that everything is running… And they are working backwards to a full Kubernetes distribution that you can install.

So ultimately, where this all goes… And to be clear, this is not a forward-looking statement as defined by the SEC… Where this ultimately goes is both teams meet in the middle. So they work backwards from Enforce to having a Kubernetes distribution, and we’re working forwards towards having an operating system for that Kubernetes distribution to run on. And that’s basically it.

And once we get to that point, we have the full stack. We have the build service, we have images, we have Enforce, and we have our own managed Kubernetes solution. And again, this is not a forward-looking statement, this is just my opinion… But in my mind, that’s where it’s going.

Yeah. That sounds like a really good idea to me, because it kind of makes sense to have a system that plugs nicely together, and all the components kind of fit. And you don’t have to end up cobbling together anything. It was all built to fit together. Now, whether that will or will not happen, it doesn’t matter. It just makes sense. So that’s what we’re saying.

Okay… Now, before we started recording about an hour ago, you said you tweeted “We discovered a bug in our repository management service.” What was the bug?

So there was a logic error in the way that certain package updates were ingested, which would cause the package update itself to get published, but the package update itself would not get published in the index. So the way that we discovered this is we have continuous vulnerability scanning of our images. Every night we run Trivy, and Grype, and Snyk against all of the public images that we produce. But there was recently a CVE with zlib, and the xlib CVE we mitigated in version 1.2.12-r3. Well, we kept getting alerts that the zlib CVE was not mitigated in our images, and we couldn’t figure out why. So last night, when somebody was investigating the alert, we’ve found out that the image had 1.2.12-r2. So we did a whole bunch of investigating into why that was the case, and we’ve found out that even though the r3 packages were published, they weren’t in the index. And if it’s not in an index, then the apk doesn’t know about it.

So basically, we were publishing the security updates, but in certain circumstances, those updates were not making their way to the index, and as a result, those updates weren’t making their way into the images, and that was triggering the scanning… And so we had to go and fix all of that. But it’s fixed now, and updates are following the way that they’re supposed to… And that’s basically all I can say about it, because it relates to an internal microservice that’s not open source.

[55:59] I see. So I’m looking at the workflow for - this is a GitHub Actions workflow for Alpine base. This is in the Chainguard Images GitHub repo, and I’m seeing the following jobs. There’s built, there’s a scan, and then there’s generate readme. And I think the generate readme is more like a publish, I think, sort of. So was the bug happening before build?

Yes.

Right. Okay. Cool, cool, cool. And then scan is the job that was finding the issue, is that right?

Correct.

Okay, and the scan – I can see the three scanners, and we’ll add the link to the show notes… There is a – Snyk, I think you mentioned, Grype… And that’s it. Is there a third one that use?

Trivy.

Trivy. Okay. Oh, yes, I’ve heard of Trivy, yes. Oh, I can see there, trivy count. Okay. So what I didn’t understand is what actually publishes the images. Because there’s the build, there’s the scan, and there’s the readme, which just updates the read me… Which step publishes the images?

Build. Apko has an apko publish command, which does the build and also publishes at the same time.

Oh, I see. Okay.

So that’s what we use in our build process for the images.

Okay. And then obviously, if the scanning fails, you don’t update the readme, so while the images have been pushed, you don’t update any of the resources that users would use, for example, in their own manifests, wherever they use them, for the image references.

Not exactly, no. The readme runs regardless. The scanning that we do is basically informational for our own internal use, so that if a customer comes to us and says “There’s this CVE in this image”, we already know about it. That’s the goal of having the scanning step, is just to ensure that our own internal team is already tracking it.

Okay. Okay. You worked around Bazel, or you worked around not using Bazel by building a Linux distribution. That’s crazy, by the way. Crazy good. I admire you for doing that. That’s just like next level of commitment, and next level “I’m going to fix this my way, because dang it, Bazel, I’m not using you.” So I think Bazel in this case was the catalyst for something amazing, I think.

Do you have any other crazy ideas like this one in the works? Because this has been going on for a while, right? Witchery, and different things coming together in a very interesting way. I think Wolfi OS is a great story, that spanned a couple of years. Do you have any other similar things that you’re working on?

At the moment, not really. Most of my time is dedicated to Wolfi at the moment. But down the line I’m sure there’ll be something else.

[58:58] Okay. What about platform support? That’s one thing which we didn’t talk about… Like, which platforms does Wolfi support? I’m thinking ARM, versus Intel, versus something else.

So at the moment, we’re only targeting x86 for Wolfi. But one of the things that is actively being worked on as we speak - because I just saw an update in Slack about it - is ARM support for Wolfi. Those are the two that we’re targeting right now. Our goals for Wolfi are a lot different than like Alpine, where they support every architecture anybody remotely uses today… But those two we believe are the sweet spot, because they represent like 99 point some amount of nines of container usage.

I know that’s the x86 is 64-bit only. Do you have plans for a 32-bit?

No.

No. Okay. Cool. Next week is KubeCon. Are you going?

I was thinking about going, but we’re like in the middle of another COVID wave… And the idea of being in a room with like 20,000 people is not really attractive to me. Also, I’m in the process of moving to Seattle, so I’m going to be sitting here, packing my stuff… And I’m sitting that one out.

Definitely more important, for sure. Why Seattle?

The majority of my friends have moved to Seattle, or they’ve moved out of the country. Right now, with the war in Ukraine being a thing, I would not like to be on the same continent as that… So I decided – like, originally, I was going to move to the Netherlands. But then the war in Ukraine broke out, and I decided that it would probably be best to wait for that to play out before moving to Europe.

I think that Seattle is probably the closest thing you can get to a European kind of mindset, while still being in the US. People there are forward-thinking, there’s a lack of bias towards people… There’s a general attempt to be friendly, and all of that, so…

Okay. Well, good luck with your move. That sounds very important. I want it to go as smoothly as it can. I’m looking very much forward to where you take Wolfi OS next. ARM support sounds like a big deal to me. I’m really looking forward to that. And more container images. There’s the Elixir one, which I will try to contribute, depending on time. I would really like that for the Changelog image, the one that runs the whole Changelog application, and website, and all of that… So that’d be really cool. But otherwise, this was a great conversation. Thank you very much, Ariadne, and I’m looking forward to what happens with Wolfi OS next year.

See you soon.

Thank you.

Our transcripts are open source on GitHub. Improvements are welcome. 💚