Peter Bourgon joined the show to talk about Go kit, microservices, Go in the enterprise, dependency management, and writing Go packages.

Featuring

Sponsors

Linode – Our cloud server of choice. Get one of the fastest, most efficient SSD cloud servers for only $5/mo. Use the code changelog2017 to get 4 months free!

Fastly – Our bandwidth partner. Fastly powers fast, secure, and scalable digital experiences. Move beyond your content delivery network to their powerful edge cloud platform.

Backtrace – Reduce your time to resolution. Go beyond stacktraces and logs. Get to the root cause quickly with deep application introspection at your fingertips.

Minio – Minio is an Amazon S3 compatible object storage server built for cloud application developers and devops. It’s also open source!

Notes & Links

- The panel shared that time they all used Go Channels incorrectly

- Go kit is a distributed programming toolkit for building microservices in large organizations. We solve common problems in distributed systems, so you can focus on your business logic.

- Go best practices, six years in

- Go in the Modern Enterprise and Go Kit

- Peter mentioned So you want to write a package manager which is a DEEP article, estimated at 50 minutes to read

Free Software Friday

- Scott — zetcd lets you serve zookeeper with etcd

- Erik — Pelikan is Twitter’s unified cache backend

- Peter — The Platinum Searcher is a code search tool similar to

ackandthe_silver_searcher(ag). It supports multi platforms and multi encodings.

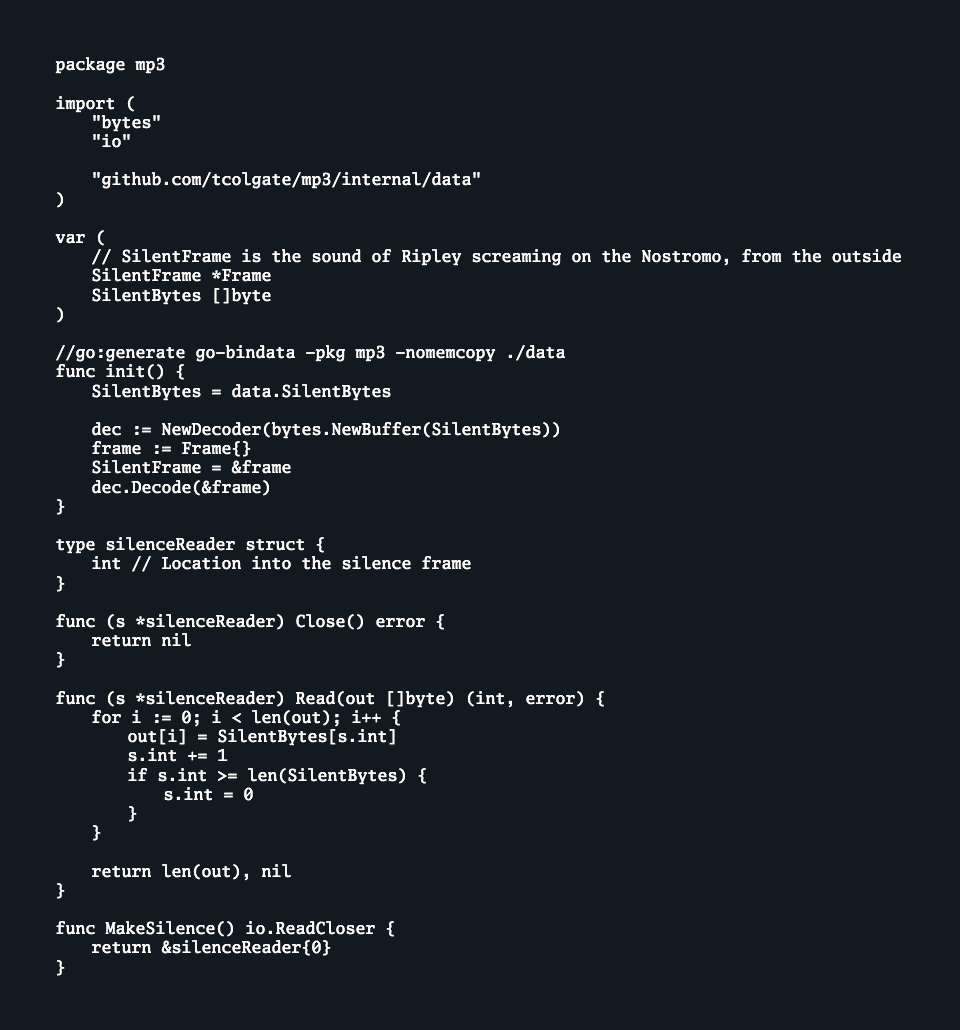

Go source code looks particularly good when displayed in Go fonts.

Transcript

Play the audio to listen along while you enjoy the transcript. 🎧

We are back, it is episode #25 of GoTime. Today’s sponsors are Minio and Backtrace. On the panel today we have myself, Erik St. Martin, we also have Carlisia Campos - say hello, Carlisia.

Hi, everybody!

And Brian is off doing some training and stuff, so Scott Mansfield from Netflix has joined us today as part of the panel. Say hello, Scott.

Hello Scott. [laughter]

You actually took that literally. That works. And our special guest today joining us on the panel is Peter Bourgon. Say hello, Peter.

Hello, and I am not special in any way.

You are special! Peter is like a staple in the Go community. You’ve been giving people advice on running Go in production longer than most people have known about Go. You spoke in 2014 on advice for running Go in production…?

Was that the first GopherCon, 2014?

Yeah, that was the first GopherCon.

Yeah, that was us back then… Soundcloud days.

So you wanna give everybody a little background and backstory for anybody who’s not familiar with you and the stuff you work on?

Sure. I came to Go after a relatively long career doing C++ actually, so I was one of the few people that actually tracked how Rob and the original crew thought people might come to Go. I was writing mostly network servers, I guess. I was working at the time in kind of a distributed search space, and when Go was released, I happened to be on sort of a sabbatical, so I got to spend a lot of time with it in the early days, and it really piqued my interest, and I had a lot of fun doing some introductory projects. I think my first thing that I ever did was probably something that a lot of people start with.

I tried to think of an algorithm that would really benefit from concurrency, so I thought “I know, I’ll implement naive Quicksort, and I think I gave each partition task its own goroutine, and I got really annoyed that it was actually slower than doing it all in a single goroutine. Has anyone on the panel ever tried something like that before? Like, first attempts, and being quite disappointed with how it turned out?

I’m trying to think of some of the original ones… See, this is where I start to fall under your same memory problem - I vaguely remember some stuff, but what was it? I know there’s some things with my own misunderstanding of the language that kind of fell flat, but I don’t know whether implementing a specific algorithm… I can’t think of an exact…

I struggled with the concurrency stuff for a little while; my pet project at the time was this synthesizer thing which never really got anywhere, but I started off by sending individual float32s down the channel. That doesn’t work. You need to buffer those up.

Anyway, so I dug in and managed to introduce it at my next job in a small capacity, and became even more interested and started building a lot of typical things out, like a proxy… I think my first project that stuck around was this key/value store. I guess everyone either does that, or a web router; one of the two things.

[03:57] And then I joined Soundcloud, where I was able to do it full-time, and there were a couple of people already working in Go at Soundcloud, actually. They formed the original Berlin Go users group back in late 2011, which was - if my memory serves, and it doesn’t - pre-1.0, so that was back in the R59 days… Does anyone remember those?

I remember those… I remember makefiles.

Oh yeah.

No Go tool, makefiles.

No Go tool. GC, 6G, 6L… Yeah, sure.

Yeah.

Yeah, so at Soundcloud we sort of built out sort of an internal platform that was all in Go. I was on a team that did some – again, it happened to be the search/discovery team; all of our internal infrastructure and applications were written in Go, and there were a couple other teams scattered throughout the company that really liked Go at that early stage. I think some of them were in the internet-facing teams, or some of the transcoding teams… Yeah, so Go services were kind of scattered throughout.

So we built up a relatively good background of early Go tips and tricks, and we made a lot of mistakes, and corrected for them, and all of that information… I conducted some interviews and scribbled some ideas together from different teams throughout the company. I probably interviewed about six or eight different teams back then. Those interviews and those learnings became the basis of that first talk at the first GopherCon.

It’s interesting… You’ve kind of spoken about the horror stories, like being disappointed, or things that we’ve done incorrectly. I’d actually like to circle back to some of those… Does everybody have an example of one that they remember that went horribly wrong? Something you viewed about the language incorrectly and used incorrectly and it kind of fell flat? I know personally I abused channels like no tomorrow in the early Go days. I see code that I wrote back then and I’m just very disappointed in myself. Like, why did I think that that was a good idea?

Super common, I think.

Yeah, I think so too. I don’t know, when I came into Go things were already rolling, and a lot of people to give advice… So when I started to write channels the first time, I quickly got advice to just “use a mutex here, you don’t need it.” So I was like, “Oh, that’s a thing…” and I looked into it and I’m like, “Okay, you can’t use channels all the time.”

Yeah, I would use them for state.

I’m lucky that most of my beginning code is in the same project that I’m still working on, so it’s all been kind of rewritten. That just erases that bad memory…

[laughs] You don’t have to look at it anymore…

Exactly.

Yeah, well that’s the hard part, too - if you put stuff out in the open source world, it kind of lives on forever, even past the point where you look at it and you’re like, “Yeah, nobody should be using this.”

I don’t know if I remember any specific horror story, but I definitely remember it took me a long time to really grok the subtleties of interfaces.

Yeah, I’d agree, too. I always forget what the exact error is, but one of the confusing parts for me was in the early days with interfaces when you’d pass something as a value or a pointer, and it needed a pointer receiver. If it expected a pointer receiver on the method it would work, but if you passed a value it wouldn’t work, and you’d get an error and there was always confusion about why that didn’t work until I looked into actually how interfaces are built. When you look at them, there’s actually a value inside of it, as well as a pointer to the type, so it’s like “Well, it can make a pointer to the value, but it can’t make a value from the pointer, or vice versa.” That used to mess with me all the time, because I’d be like, “Why does it work one way but not the other?”

[08:07] Somebody gave a talk about that one at the Go Language team members, I’ve forgot who, and there was a good explanation. But yeah, it’s not easy; you don’t find this information right away when you start learning. Even now…

Well, I guess it exists in the form of the language spec, right? That’s actually a really good place, in the Memory Model. I remember reading the Memory Model, and that started solidifying a lot of concepts to me, about ordering, how the compiler can actually reorder your statements, so you can’t actually guarantee when this is run concurrently that these things are gonna happen before each other just because you put them in the code that way, and that really started helping with my knowledge. But I think you have to have some experience. You kind of have to find your way around first, and develop some battle scars and then read it, because then you have something to relate it to.

Yeah.

Totally.

If you just read the language spec and the Memory Model you’re like, “Okay”, and then you’re gonna still make the same mistakes.

Yeah, I agree.

This is a trap I find myself falling into whenever I’m trying to teach newcomers, or give advice sometimes. Everything I learned was a function of my doing it the wrong way once, and then kind of realizing it’s the wrong way. It’s a very didactic process, and I think most people probably work in a similar way, so it’s actually not very helpful to just tell them, “This is the right way, you’re doing it wrong.” You have to kind of show them what the problems are, and let them feel the pain, so to speak.

Yeah. I know that I never actually learned any new language or any new concept without going and implementing something in that language, or just trying to implement that concept. It just doesn’t stick.

Yeah, there’s that balance… Like, how do you get enough knowledge to not be totally falling on your face, but be developing enough battle scars from doing it where you can kind of start to understand what’s going on.

And talking about learning and teaching, Peter, I see that you are now giving workshops. Do you plan to continue? How’s that going?

Yeah, I guess there’s a couple of topics that are sort of in my wheelhouse and it depends on the audience. I’ve given basically Go training from zero, and kind of a tour of the language, and it gets the class up to reasonably sophisticated Go programming. In that course, I just walk through all the language features and do some tour exercises, and step through docs like the Memory Model and Effective Go, and explain how all the orthogonal pieces interact.

So I’ve done that a couple of times in different setting and different lengths… And that’s okay, that’s kind of rewarding. The main thing for me is just to get more people into the ecosystem, and maybe this is hubris, but kind of point them down the right paths, rather than encouraging them to build yet another HTTP request muxer, or whatever the thing may be. There’s maybe more interesting projects to get your feet wet with. And then lately I’ve been doing quite a lot of stuff around the topic of microservices, and Go Kit comes into play there absolutely, but I think that there’s also another way to look at teaching the language, a very service-oriented or server-oriented way of approaching and introduction to the language that seems to me to get a bit more traction in the sense that people more quickly understand the strengths and the values of Go, and they kind of say, “Oh, this actually compares very favorably to how I have to currently do things in Python, or in Spring Boot”, or whatever the framework of the day is.

These are quite popular workshops, especially at typical conferences like GoTo or QCon, or some that I’ve done lately.

[12:10] I love that idea. I wish you would maybe write about it. Is there a book in the works maybe? [laughter]

A book, good lord…

You’re putting work on his plate for him. You’re committed now.

I’m delegating. [laughter]

Goodness…

No, it really is to me I think very useful to have an approach to teaching the language that highlights its best features. There are many ways of teaching things, and I think people make use of different ways in this way of teaching that – I don’t remember exactly how you said it, but presenting the language in a way that it’s a… How did you say it, in a service-oriented way?

Through the lens of servers, yeah.

Right, because it’s so much of what we do, and especially what we do with Go, so it’s super useful.

Yeah, I totally agree.

So the microservices thing is kind of like another explosion in recent years too, and we see a lot of frameworks in many different languages, and orchestration platforms, and service discovery and things like that. Let’s talk a little bit about that and your passion for that, because you’ve kind of been in that world for almost as long as you’ve been Go. Kind of learning and building your view of the world and how it should work, and advocating to people how to do this successfully.

Yeah, I guess there’s two angles on this. There’s the why is it interesting to me at sort of a high level, and then there’s the why do I think Go is a great match at a technical level.

I’ll start with the first, I guess. I was really doing microservicey type stuff for quite a long time; of course, it didn’t have that name until very recently. I really only dove into what we commonly know as microservice workloads today, when I was at Soundcloud, and we kind of made an executive decision - or at least an engineering department decision - that this was probably gonna be the future and we should probably invest some resources into building out an architecture that worked in this manner. At the beginning I think I was the first team that was using our internal platform and kind of the prototype customer, but I was really excited to try it out, because it got at something that I couldn’t quite put the word at the time, but which I really have thought a lot about, and I think I can describe it properly, now that I’m a few years removed. And that is this experience I had in previous companies where it would be my first day or my first week on the job, and I would join a team, and there would be this existing codebase that to my eyes was just massive, and full of dark corners and unexpected interactions, and a lot of legacy… Not necessarily croft, but just legacy knowledge baked into it. And the only way to become comfortable in that environment was to put in a whole lot of grunt work that you couldn’t really rush and you couldn’t really optimize.

You had to read the code, but that was never enough; you had to go and ask people why things were the way that they were, and sort of probe them with intelligent questions about, “Well, did you consider this alternative? Oh, okay, you did and didn’t work out for these reasons… What implications does that have on this other part of the system?” So for me it was always a multi-month process to get my head around a new system, and what I sort of discovered with microservices was that this cost was dramatically reduced when the size of an individual codebase with well-defined boundaries was much smaller. In my workshops I say one good definition of a microservice is “Code that you can keep in your head”, and I think that’s a really great way to delineate a boundary for this sort of thing. [16:03] It’s code that you can totally keep in your layer two cache, in your brain, or whatever, and that implies that you can pretty well describe it with a single sheet of paper and 15 minutes to a co-worker. And maybe there are a couple of edge cases and dark corners in there, but it’s not the sort of stuff you need to dedicate half a year to figuring out. And if this is true, if this is how your organization’s built, like a loose constellation of these sorts of codebases, then it’s much easier to move between them, to understand them, to understand the interaction points - at least for me, at least for the way I model software. And in turn, it gives you a lot more confidence - when you join a new team or you start a new project or you take over an existing project - to refactor it perhaps, if the requirements change, or to make changes and maintain it, and have confidence that you’re doing that in the right way.

That’s sort of the soft side, it’s why I love microservices. They make me confident again, and they give me a certain amount of happiness that I lost when I was working on gigantic years-old legacy monoliths or huge projects like that. That was a lot of talk, I’m sorry for taking the floor.

It’s your floor to take.

That was a great explanation, and I love this idea of the ideal size of a codebase being whatever amount that you can hold that in your head as a mental model. This has been coming up over and over again when we talk about microservices.

I think it applies to a lot of things though, too. Recently I was talking to some people at KubeCon last week or the week before, and I used almost the same premise for whether or not you should use something like Kubernetes like an orchestration platform, and my example was if you can’t name me all of your hostnames, and you can’t say like ChicagoWeb01-30, that doesn’t count… But if you can’t reasonably name off all of your host, you probably shouldn’t be managing them individually. You should be doing something to orchestrate those and provision them and manage them at a higher level of abstraction. I think that that’s the reasonable thing…

And in management too, right? From your perspective, when you have an organization with a big monolithic project, it takes a lot more coordination between teams, that are seemingly unrelated, but because now they’re in the same codebase, the projects are more tightly coupled together than they need to be.

Yeah, and as ever, it’s this balance. There’s a spectrum between – I like this word, “balkanization”, where everything is its own separate service; you can take that to an extreme, of course, and you just have to look at the architecture diagrams from Uber, or whatever… It’s like a thousand microservices, many of which are duplicated because teams just don’t know about existing functionality necessarily. So you can definitely take it too far.

Now I guess we’re getting a bit to the technical side, and this is a point that I’m very clear to make - whenever you move away from a monolith or you start down this path of giving each developer a set of their own independent microservices to manage, you’re actually creating way more technical problems for yourself, in so many dimensions, than you’re solving. And what microservices enable is organizational harmony, and they improve shipping velocity, and they improve communication overhead, and exactly as you said, coordination in a single codebase - when that becomes too hard, then microservices can help.

[19:48] Let me give you a counterpoint to this kind of argument. You can do the same thing in a big monolith - you have very well-defined interfaces, for example, between each packages, and then you don’t have to worry about the vagaries of going over the network every time you want something. What do you say to that?

Absolutely. I think the term that gets batted around for that architecture is the “elegant monolith” style, where everything is pretty well delineated internally. There’s not a lot of shared code, very well-defined API boundaries… It’s just that the deployment artifact is all hosted in a single process, which carries a huge number of advantages; atomic refactors, and the deployment story is significantly easier, the testing story is way easier… Yeah, so this is a great thing to do, especially if you’re just getting started.

When I give my little workshops, I say “If you’re five engineers or fewer, there’s no reason that you should be running a microservice architecture.” You’re just not having any of the problems that microservices solve. This architecture you describe is a great alternative, and one that you can kind of adapt to microservices as you grow and become more successful.

Yeah, I saw Peter’s talk at Golang UK and he was very discouraging of using microservices. [laughter] And I really liked it because he went through all the pain points, some obvious, some not so obvious - obviously, he has a ton of experience - and he went through many pain points that you can go through by having a microservice if you are not really properly set up for it, like he was saying. If you are super small, you don’t need to divide your codebase in many microservices.

But at the same time, Scott’s remark is to the point I think, because as I have been learning more about packaging in Go in the recent months, Go makes it so easy to really contain your code through the use of packages. I wonder if for Go the heuristics would be different as far as a feasible size for a codebase.

Do you think it would be bigger or smaller, Carlisia?

I’m wondering if it could not be bigger and still be very functional, if you use the features of the packaging; now there’s that internal feature which allows you to hide even more things. And there are companies using monolithical apps, like Digital Ocean, and there’s another one that I forgot now.

Yeah, I think it’s completely viable. I guess I don’t have the stamina to give my workshop again here, but there’s so many problems that come when you’re splitting your business domain along process boundaries. If you can avoid doing that, if you can split it on package boundaries and then wire things up internally with some interprocess or intraprocess communication layer rather than JSON or HTTP or whatever… And package boundaries make a good proxy for that sort of thing. Although then you start entering this still quite confusing for me domain of how do you structure your repo? How do you decide where to cut up your packages?

Ben Johnson has an opinion about this, but I’ve tried to use it and it often fails for me. Maybe I’m holding it wrong. There’s lots of opinions about this sort of thing; I’d love to hold a panel about that as well.

I would, too. I’m super interested in that. By the way, the other company I was thinking about was Google. Google has a single repo. But yeah, Ben Johnson was talking about that, Bill Kennedy promised that he’s going to start writing about that as well… I’m working on a talk and a blog post about packaging, although mine’s going to be more like entry-level than one of you guys. But personally, I can’t even imagine working with a monorepo. Just the whole “deploy everything everytime, run every single test everytime or at least once in a while…” I can’t imagine.

[24:19] It depends on how coupled your repos are. If you have multiple repos that are highly coupled to each other, then the testing story and deployment story gets more complicated with that, too.

I think it’s interesting, because a monorepo can still be broken up, right? If you look at the Kubernetes codebase, or the Docker codebase, there’s a command directory which kind of has the main packages in it, and then there’s like a package directory that has code implementations of those things. So there’s still areas of the repo that are kind of siloed off for these particular things, but you can guarantee that when you make changes to the Kube control binary, which is the command line interface for interacting with Kubernetes, you can ensure that it doesn’t break against new versions of stuff when it’s all tested together.

It’s really hard though, because anybody who’s worked for companies large and small, you start “Well, it’s good for these scenarios but bad for these others” and you can join the other team depending on kind of what the exact use case is. I love monorepos for many reasons, and then I love splitting it up for others. I feel like there’s no easy win either way. And I feel the same way about breaking up packages, like where the package boundaries are defined. As long as I’ve been doing this, I still can’t find a way that I like. I feel like “This worked for this one time, but it’s terrible for another project”, and it sounds like that’s a struggle everybody’s having.

I haven’t seen Ben Johnson’s post on what he’s recommending there… At least I don’t remember it. It might be my seven-day window thing. I need to look at that. Is that on his Medium blog?

Yeah, he has a blog post and he has a repo with an example. And actually, if you look through the pull request, there’s quite an instructional conversation between Peter and Ben going over the tradeoffs, it’s very interesting. One thing’s for sure - a monorepo would make it easy for dependencies, so maybe we should talk about that.

Yeah, so I wanna get into dependencies and I wanna get into Go Kit a bit. But before we do that, it is time for our first sponsor break.

[\00:26:46.05]

Okay, moving on. Carlisia, you wanted to talk about…

Dependency management.

Dependency management!

That little thing… [laughter]

That tiny little problem nobody has, right?

Yeah.

Peter, I know you have a lot of views on this, and some of the tooling and how things have evolved, and you’ve kind of followed this all the way through its course, which has been “As long as it’s solved…”

Quite on the contrary… I actually have almost no strong opinions about it. What I do have a strong opinion about is that it gets solved, yeah. Precisely.

So how did this all begin? Back in the early days, in the pre-1.0 days, we all decided we should go get our dependencies, and because goget identifies projects in sort of a spacial dimension, they identify them by name, but provide no way to identify them in sort of a time dimension, there’s no way to identify version… The consequence was that we kind of all just had to trust that all of our dependencies were going to remain stable, or the changes they make weren’t going to be breaking, or if they did make breaking changes, that we would catch it somehow magically, as soon as it happened, and then make changes to fix it somehow, magically.

This hope-driven development worked surprisingly well for a number of years, in the sense that Go gained popularity and people were still shipping productive production software with it. But in the open source ecosystem it has sufficient differences to the Google monorepo and to the Google way of doing things, so as we all are pretty much aware I’m guessing by now, it has started to fall over in the broader ecosystem for me that the hardest thing to deal with was actually when I started programming against Kubernetes’ APIs. Has anyone tried to do that?

Yes.

Goodness…

And ouch! Very much ouch! I’m building stuff against their APIs too, and there’s two problems. One, before they did the client Go library, which is just the client libraries, you had to import the entire Kubernetes package, which was terrible. Then the second problem is nested vendoring.

Following this course, in the early days I almost agreed with Google. Like yeah, you don’t really, but you forget that in the early days there wasn’t a lot of libraries, so you ended up writing a lot of your own stuff, so it just really wasn’t a problem.

And the libraries that did exist were relatively small, so you didn’t have this huge vendor tree problem, you didn’t have this “dependencies of dependencies of dependencies” problem.

Exactly. They were relatively small, served a very distinct problem, and you could either copy the one part of code you needed, or… It was very small, but you didn’t have this tree of vendor directories, where it’s like “Great, now I have Kubernetes vendored in, but how do I get it to recognize their vendors, and what happens when they have vendored the same libraries that I have vendored, because I’m using them for different purposes.

Exactly. So a lot of people saw this coming, and a lot of really smart people started developing tools to manage the vendor directory as what we kind of all settled on as the place to store your dependencies. That’s fine - you can check it in, you can not check it in… It kind of doesn’t matter. And this approach, the blooming of a thousand flowers by all the contributors was kind of blessed by the core Go people. They wanted to have “the community” solve this problem, and then when a solution emerged, I guess they didn’t say this explicitly, but I guess they would have blessed it somehow, and then that’s what people would all choose to use.

[32:00] Unfortunately, that was I think in retrospect quite naive, because what ended up happening was we have 13 standards of ways to manage dependencies, and that means different file types, different file locations, different file formats, different behaviors in all the tools. Broadly, you can say that they do very similar things in very similar ways, but there’s subtleties in the differences.

In the end, it means that when you publish a package and you have dependencies and you want to - I guess it’s a pretty sane thing to want to do - bind your code with specific versions of its dependencies, then you’re necessarily kind of opting into one of these tool ecosystems, but there’s so many that in order to consume different packages, you end up having to support all of them. And since none of them are part of the standard Go tooling, then you’re kind of like telling your consumers they need to opt in to not only the Go tool, but these other third-party things which have their own project lifecycles and bugs and all these things.

So it’s a total mess. And while you can always find a path through the storm and solve something for your specific use case or for your specific project, there’s no single coherent, teachable, simple way to solve this problem generally. So that was the state of the world.

Even if we all as a panel said you should use this one, it’s not gonna matter because of that whole nested dependency problem, right? I use one, but I import a package that uses another one…

I think it was super naive in retrospect to say “The community is gonna figure it out”, because what happened was you have these camps, and they kind of ossified and for good reasons - everybody has reasonably good reasons for choosing one style or another, but now we have all these competing standards. So in my mind, the only way out of this is to - and I guess this is where we’re getting - form a committee with representation from the core team, and pick a standard. Maybe that takes the form of blessing one of the existing tools officially, or maybe it takes the form of producing a hybrid tool, or a common tool, or something like that.

This is the committee that I was driving as of a couple months ago, and that’s what we’re in the process of doing right now, to kind of eliminate this heterogeneity in this space, and hopefully help a lot of people.

So just to get things clear, you’re not the head of the committee anymore?

Right, so I was never on the committee… Basically, what happened was I had a number of weeks at my day job where I was working with people trying to get a handle on the dependency management story, and was being confronted with all these tools and workflows, and they were broken for our use cases in subtle ways, and we filed bugs… People were just getting pissed off, frankly, and many of them were - and I saw this also in the broader community - kind of saying, “You know what? I’m not interested in programming Go anymore if this is the way it’s gonna be.” And this was really super sad for me.

So I just kind of said, “Forget it… I think I have enough political capital in the Go community that I can kind of anoint myself the person who’s gonna figure this out, but I don’t have enough political or technical know-how to actually do it myself.” So I said, “I’m gonna be sort of the communications director, or the PR person, and I’m gonna organize a committee of people whom everyone trusts, hopefully, and they’re gonna figure it out. I’m just gonna be the organizational person.” I’m gonna run interference and try to be a firewall and help them achieve that goal. So yeah, I’m not on the committee, I’m just figuring out all the logistics, I guess.

[36:08] Alright, so you’re still heading it, though.

Yeah, I guess.

You’re heading the initiative.

Yeah, you could say that.

And what is the state of the prototype that’s being built? Has it been made open?

Not yet. The workflow was we first in a Google Doc describe what I want the process to be, we took some feedback on that (it was great), then we picked the committee, and it actually ended up being a core committee of Andrew Gerrand, Jessie Frazelle, Ed Miller and Sam Boyer, whom you know from the extremely lengthy “So You Wanna Build A Package Manager” Medium article; I think the estimated reading time was like 45 minutes, or something like this. Super, super, excellent article.

So they’re the core committee, and then we have this sort of trusted advisory group of the authors and maintainers of the top four tools at the moment, which are Matt Farina of Glide, Daniel Theophanes (I’m sure I’m butchering that name, I’m sorry Daniel), he’s the Govendor chap, Dave Cheney of gb, which is kind of the odd duck in the group, and then Steve Francia, who is kind of like a Go liaison now at Google, and he’s been doing a lot of work in this space, as well. So it’s these people that are sort of driving it, and to answer your question - the implementation is currently under way. We went through a long period of building a spec for the thing, got some feedback on that and the implementation’s now basically being implemented… A prototype implementation by this core committee. That’s not open yet, because we wanna have something at least minimally usable before we make the repo public.

Gotcha.

And to clarify - this is going to be kind of a new approach based on the knowledge of people who have already developed tools, and not some way of interacting with these specs that already exist.

Right. What we did was an extensive, comprehensive survey of the states of the ecosystem, both in Go and in other languages. We consulted with all of the authors about the pain points that they experienced and if they wanted to represent their user’s experience, and what things they found to be super important, the most important top K features, or whatever. And then we took feedback from the community based on user stories, based on design points… There’s a whole bunch of questions. “Should the tool in this scenario do this or that? How should it interact with the GOPATH? How should it manage version ranges?” and so on and so forth.

Each of these questions has a wide variety of possible answers, so we enumerated all those as best we could. Then, with this “survey” of possible use cases and design space points and user stories and all these things, we winnowed it down to what we considered to be the bare minimum usable, covering 90% of the use case tool, and it ended up being quite a small surface area, so not too many subcommands. Then we made that spec, the spec of such a tool public, and we took feedback on that. So yeah, it’s sort of like lessons learned, and hopefully a common ground between what everybody’s doing.

From where you stand now Peter, what do you see as a possible timeline for this coming together as a production-ready tool for vendoring? If it goes on the path that it’s going now; of course, if people say it needs to change, then who knows…? But if it goes on the path that’s going now and there is agreement - there will never be consensus, but if it proves itself useful the way it’s coming along, what do you see as far as timeline?

[40:05] That’s a great question. My hope at this point is that we’re gonna have a usable prototype by the end of the year timeframe, and luckily it’s going to be a tool that you can kind of go get independently of anything else, and you can kind of try it out. We’re gonna have a period of use, I guess, refinement, iteration…

At this point I hope interested members of the community are going to be filing issues and potentially even PRs on it, and then the goal, at least as I understand it now - and this is all subject to change, of course - would be that this dependency management tool would become packaged into the Go tool, so a separate Go space dep, let’s say (subcommand) in the 1.9 timeframe. So that’s the hope at the moment. Who’s to say if it’s gonna get there, but even if it doesn’t get in the Go tool, it will be usable separately.

I think the nice thing about it being in the Go tool is that it becomes the canonical thing people use. Because that’s the hardest part, right? Once this thing it’s released, it’s just another one in the sea, and then we’re still gonna have the issues of “I’m using that tool, but I’m vendoring things that use another tool.” I think as soon as it’s kind of adopted by the Go tool, it becomes kind of the standard, and people start porting to use it, and the ecosystem becomes friendlier for everybody.

Exactly… Scott has just pasted in the Slack channel… [laughs] The problem here is exactly the number of competing standards. The usability problems introduced by having all these tools is exactly what needs to get fixed, and in a lot of ways that’s really hard, because you don’t want to – we’ve only learned the lessons we have from all these incredibly smart people putting in the hours and the dedication to making their tools as good as they are. But at the end of the day, if you wanna have a reasonable, coherent ecosystem, you can’t have arbitrary installation instructions for every arbitrary package that you come across.

You really do need the single standard, and we’re gonna do our best to make that transition period as easy as possible. There’s a couple of options for that. We can read the most popular existing file formats and kind of do the transition automatically, or we can have a transition tool that’s packaged beside the dep management tool. We haven’t quite figured out what that’s gonna look like, but we’re committed to making the transition UX about as good as it can be.

Even if there’s a secondary process that I have to download to fix my vendor directory… I don’t care that you use this, because I can fix that, and just kind of run something that reads their vendor file and flattens it out onto yours, or however that works.

…for example, yeah.

The hard part too here is I think we’re critical on the Go team, too. I think it was naive, but I also kind of understand where they were coming from, where it’s not really a language thing, it’s an ecosystem thing. But I also argue that there’s many things in the language that were brought in that were ecosystem things, which has actually helped adoption. The Go tool - everybody uses that now. I think that that made the language so much more approachable when everything kind of got bundled into the Go tool.

[43:46] Arguably the great lesson of the Go experiment is that you can’t really treat the language and its tooling ecosystem in isolation. They are really part of a package that developers buy into as a whole, and I think that that understanding has really helped Go, and the commitment to gorename, gofix, go fmt, govet, golint - all these things packed together in a way that makes a compelling developer experience.

Are you familiar with the Rails world?

Only peripherally.

I wonder how much of what everybody loves about Go is a similar thing that people loved Rails for, which is that convention over configuration thing. There’s just this canonical way of doing things, and that makes it much more approachable. You’re not looking at 50 ways of doing this, and the paradox of choice, where you can’t figure out which decision is the best for you and you just don’t make a decision. The Go tooling has kind of taken that away, like “How do I format my code? What are the proper idioms?” and things like that. It’s kind of well defined.

It’s certainly what attracted me to the language early on. And what kept me away from Ruby - less so Rail, more so Ruby - is that in Go (and not Ruby) there’s only one way to do something. Those limits, paradoxically, give me the freedom to worry about the problem domain and not about my method of expressing it.

Yeah, I love that.

Scott, you’re firing shots on the GoTime FM channel… Aliases! [laughs] Hand grenade!

Yeah… There was one point that I wanted to bring up that I thought was very good in the document that is out there now for comment. The idea of keeping this very restrictive, but also just simply dropping some of the more complex requirements I think is going to work out the best, because keeping that area small, that purview small to begin with is going to let you actually observe in the real world what the problems are. And I think too many people earlier, part of the churn, especially in the vendor channel on the Slack, was around all these complex use cases that people could just come up with all day. But having something out there and operating in the real world is going to get you the proper tooling.

I totally agree. It’s very easy to come up with a convoluted workflow that breaks any tool you can imagine, and all you have to do is stamp a “Required” on that workflow, and suddenly you’re back to square zero. What do you do?

And I think some of it comes from – you know, all of us come from different languages that already had package managers that worked a particular way, so you’re influenced by the idioms that you used programming in the language. I think that’s where we see some of these patterns from all of these different tools - the influence from the package managers they came from.

I think the perceived use cases come from that, too. The language itself is the same way. You’re like, “Oh, well I need this language feature because I need to be able to do this”, but really there’s another way it can be done if you view it from the language perspective. So it’s kind of the same way here. We have to think about it from Go’s world. No language actually has import paths, like actual URLs as their import path, so we’re already kind of in a whole new world.

Scott, did you wanna talk about aliases, or you’re just throwing jokes here? [laughter]

No, that’s purely me trolling… I really don’t wanna talk about aliases.

Nobody wants to talk about alias. [laughter]

Have you talked about it yet on the program?

There was an episode I think we vaguely talked about it… Brian is very adamant that he does not want them.

Good.

Scott, you’re supposed to be playing the part of Brian today, so you should be like, “NO ALIASES!”

Okay… NO ALIASES! They’re horrible. I really don’t understand why, but I’ve been told so, so…

[48:05] That ship has sailed, you guys.

Yeah, I think it’s just because people think it creates kind of like a footgun. It’s not that it’s inherently bad, it’s just… The language has done a very good job at shielding people from creating monstrosities, you know?

You give me a day and a laptop and I can create the worst Go code you’ve ever seen, so I don’t really need aliases to do that.

Challenge accepted! [laughs] I wanna see that, too. I actually wanna see everybody’s worst Go code, like what is the worst thing you can come up with. The most racey, ugly-looking, Perl one-liner… [laughs] That’s something I don’t miss. Did anybody work in Perl in previous lives?

No, not me.

Peter, you wouldn’t remember, right? [laughter]

I remember one of the first programming books I got was like “CGI Perl” or something like this… I think that was an O’Reilly book, and I think I got about 15 pages in until I gave up pretty quickly.

I don’t miss the days where there was competition with like, “Look, I wrote an IRC client in one line of Perl!” You’re like, “But why?!”

I worked with a guy and he used to joke it was a write-only language; you didn’t modify Perl, you just wrote a new one.

Exactly. You know who’s using Perl all the time? Damian at booking.com, they’re still a Perl shop.

Yeah, they’re doing I think OOP Perl, though. I’m pretty sure that people have probably learned their lessons by now, that you don’t write applications in one line; that’s just not reasonable.

So a big project of yours is Go Kit, and I wanna get into that. But first, I think we have our second sponsor break, so everybody get a drink. Well, not everybody listening, but the people on the show.

[\00:50:02.02]

Okay, so Go Kit… We’ve started out with microservices, now we’re gonna circle back. So along the lines of your microservices love, the past couple of years now you’ve been working on a project called Go Kit, which has seemed to really be taking off, and I wanted to talk a bit about that.

Sure… So let me give a quick background, I suppose. Go Kit was born when I was at Soundcloud. We had been doing a lot… We were very heterogeneous in terms of languages, very polyglot, and Go had great representation at the beginning. When we were growing, we realized in order to achieve economies of scale we needed to settle down a bit, we needed to not be deploying Haskell code to production, because then we had about two engineers that could support that. So we started to circle around certain officially supported ecosystems, and one that everyone seemed to enjoy was Scala; there was a lot of great support in the Scala ecosystem. It was a very expressive language, lots of people interested in it. Scala had this thing called Finagle (from Twitter) which solved a lot of problems that were very common to microservice architectures.

[52:01] Another language was Go, and a lot of people really wanted to use Go, and I was kind of chief among them. But when we started deploying a lot of services, we realized that there wasn’t a Finagle equivalent; we would have had to write our own circuit breakers and rate limiters and safety stuff, and load balancers, and integration with our service discovery system. This was all work that needed to happen, and that the Scala people kind of got for free. So in the end, while Go was still being used for SRE-type tasks, infrastructural tasks, it fell out of favor in the application domain in terms of like the business logic services that drive the product. That was super sad to me, and I didn’t want that to ever happen again. I didn’t want Go to get squeezed out because it didn’t have support for this kind of architecture, so that’s what birthed Go Kit and that’s what’s been driving it so far.

Do you have a lot of users in production with it now? Do you know?

Yeah, definitely some… Although this is sort of the thing with open source projects; I haven’t tried to do an official survey or asked people to reach out to me yet, but it’s really difficult for me to get a sense of who’s actually using it, because I guess if I do my job right and my documentation is good and it doesn’t crash, then I kind of never know. Because all the repos that would be importing it – otherwise they might show up on GoDoc, as an importer, but all the repos that would be importing it are probably private. So I’m definitely aware of a couple of big uses… I’m not sure how much I can say.

I guess one frequent contributor is this fellow by the name of Bass van Beek, and he’s using it extensively in his game startup. He’s helped me a lot with distributed tracing and the gRPC transport side of things, and a couple of other things besides… And there’s definitely – I’m aware of probably about a half dozen companies… People from companies that have reached out to me and said they’re using it extensively; probably another dozen or so that say they’re using parts of it… Beyond that, it’s hard to say. I can say it has a lot of stars - that’s pretty much meaningless, isn’t it? [laughs]

That’s the difficulty, right? And that’s kind of like why we do our #FreeSoftwareFriday thing. You usually only hear from people when they’re having a problem. If it’s saving the world, they’re like, “Yeah, you know…”

Yeah, exactly.

I don’t think the stars are so meaningful. I think it shows interest… I was actually just looking at Go Kit’s channel Gopher Slack and it’s got over a thousand people.

Wow.

Yeah, that’s super surprising to me, and I guess… Actually, if you go to the Gopher Slack list of channels by members, I think it’s top five, or something.

Yeah.

Well, that’s crazy though… Because when you think about it in context, that’s 10% of all the people in the Gopher Slack, total. For one project. That’s good.

I’m into it.

Yeah, and if you’re taking into account that a lot of people are not even active, that might be more like… It’s a much higher percentage of the active members.

Right, and a lot of people don’t hang out in all of the channels. Not being in there doesn’t mean lack of participation in it too, so…

That’s always hard, like how do you measure involvement in a community (in any community)? How many Go programmers are there? It’s hard to even guess. You could be off by an order of magnitude. You try to look at projects, or conference attendees and things like that, and make an educated guess, but we’ll probably all be very wrong. There’s usually more people using a technology that aren’t active in the communities than there are people involved in the communities.

[55:52] Right… The great, dark mass of unspeaking programmers. I hear it’s like, 80% is probably a good initial estimate. You only get interaction with about 20% of your users.

Wow. I knew it was a big gap, but that’s huge. So we’re saying 80% of people who use any given technology typically aren’t visible in public communities…?

I’ve heard that statistic bandied about, but I can’t put a source to it right now. But intuitively, that kind of makes sense to me.

That’s crazy. So I know that we have talked about Go Micro on this show too, and I’d love to get your opinion on some of the other microservices frameworks and how they related to each other and what you see as benefits and drawbacks. Do you feel that you address the problem differently, that you solve a different problem? Because sometimes we perceive problems as the same.

Yeah, I would say so. I would say my approach is pretty fundamentally different to the Go Micro approach. I know him by reputation, if not super well in person; we’ve had a lot of conversation in this space, obviously… His Go Micro project is, from where I sit, it’s a lot more of a batteries-included ecosystem, I would say. And I’m sure this isn’t so strictly true anymore, but the Go Micro approach is the way to write a microservice is by opting into all of these dimensions of the problem space, and the Micro universe has point solutions for each of those dimensions.

I guess it’s a lot more opinionated in the sense that to boot up a service you’re going to implement a particular interface with lifecycle management methods on it, and you’re going to absolutely hook it up to a service discovery system and it’s going to interact with a service discovery system, and you’re absolutely going to have this control plane that exists and allows you to query the health of services, and that’s gonna be backed by this particular open source component, which you can swap out if you want… But you need something in that place, you need something doing that work. So it’s more opinionated, and as I see it, it’s kind of this universe of things.

Go Kit, in contrast, is coming from the angle of “You already have in your organization an infrastructure, and you’ve already chosen what you’re gonna use for service discovery.” Or maybe you’re not using anything for service discovery; maybe you’re doing it completely manually. Similarly with your transport layer - maybe you’re not using gRPC, maybe you’ve already standardized on Thrift, and that’s not a decision that you can change lightly. And Go Kit is going to basically allow you to bring Go into this heterogeneous infrastructure and allow you to write Go microservices that interact with these components that already exist. So it’s a much more conciliatory approach, it’s much more like playing nicely with others approach, and it’s much more focused on the software architecture of the service itself. It has much looser opinions about how it interacts with the environment. I think covering a lot of the same grounds, but just with different approaches. Does that make sense at all?

I think it does perfectly. That’s kind of where my view has always been with… You know, Micro is kind of the “Here’s your whole layout, here’s how you do everything”, and Go Kit is more of a framework that allows you to make decisions, but “Here’s some paradigms and ways that are known to work well together”, and you can kind of pick and choose.

[59:56] Exactly. And here’s integrations with these common components, common service discovery systems, common instrumentation systems. Whenever I give talks about Go Kit I say, “Fundamentally, it’s about leveling up software engineering, and leveling up the way you build microservices, like code cleanliness, separation of concerns, exclusion principles, inward-facing dependencies, clean architecture…”, it’s about all these software engineering principles applied and writ large. It’s a lot less about enforcing opinions in the architecture or infrastructural sense.

That’s quite a tall order.

How do you mean?

It takes plenty of time for an organization to adopt all those things. I guess being somewhat modular would allow them to do that, but having all of that all in one go is quite a lot to learn for people who don’t have that deeply ingrained.

“Having all of that” meaning all of these software engineering principles, or all these components?

All the software engineering principles that you just named; that’s quite a lot for people to absorb if they’re not already doing a lot of those things.

Oh, for sure. And for that reason, I view Go Kit as more than anything else a sort of educational enterprise where hopefully you can kind of start easy, start simple… There’s one big hurdle at the beginning, but then you can see okay, once you get over that, where all the other pieces line up.

I think that’s kind of the fun part too, that it’s almost like a recipe book. You come in here and you’re like, “Okay, I think the first thing we need to do is solve service discovery”, and then there’s a list of things that are known to work well together. It’s like, “Okay, let’s take on the service discovery aspect. Now, okay, we have all these services and they’re communicating with each other, but how do we do distributed tracing? Okay, let’s adopt that now. Well, what about distributed logging?” and you can kind of pick these things as projects. Adopting all of it at once is gonna be a no-go for any large organization; that’s too much risk at one time, so being able to pick these things out one at a time has its benefit… Whereas your newer grassroots efforts - those types of projects that are popping up have a lot more freedom and flexibility to kind of just adopt as much as they want in one go, because it’s a whole new effort.

Yeah, totally. And if you’re a two or three-man shop and you’re starting fresh on brand new infrastructure, maybe Go Kit is a bit too much of an initial hurdle. Maybe there’s too much there, and maybe you get a lot more productivity by starting with something like Go Micro where a lot of the decisions are already kind of laid out for you. I think that’s totally viable.

The other thing I wanna point out just looking through the list of all the things that are available in Go Kit (the list of components) is four years ago we were writing almost all of our Go code from scratch, and now nobody’s implementing new service discovery mechanisms really, right? Those things already exist.

I hope not.

It’s just crazy to think that stuff - that things that four years ago everybody had to build for themselves, we just don’t even worry about it anymore. When you see somebody build it for themselves, you’re like “But why?!”

Peter, give us some insights here as far as interoperation between Go Kit and other things, or self-written code. Can you use Go Kit logging together with Micro, or together with my own code, or just metrics? Is it possible?

[01:03:46.09] Yeah, totally. In Go Kit there’s a bunch of packages, and I would broadly say there’s two types of packages - there’s ones that you can use completely independent of anything else, that you can drop into your existing codebase with no other changes and just reap the benefits of that particular package. So logging is a great example. Chris Hines who was an early contributor and who basically should take all the credit for everything good in logging - we worked together and he drove the creation of this unified logging interface, which I think is really wonderful to use; it’s structured logging. We are strongly opinionated that structured logging is the way you should do logging in this sort of environment. And a bunch of supporting infrastructure around it. So you can use that package completely independently. I’m biased, but you should. You should definitely look into using that.

Same thing with metrics, for example. The instrumentation package defines a set of common interfaces that are broadly applicable, and implementations that connect it to (I think the latest count was) 8 or 9 common metric and instrumentation systems, Prometheus being chief among them, in my view. So this type of stuff you can use right away.

There’s other packages that sort of rely on your microservice being structured in a particular way, using the endpoint abstraction and the transport abstraction. This requires a bit more buy-in, that’s kind of the hurdle I was talking about. But if you jump over that hurdle, if you buy into these abstractions that I’ve laid out, then you get to leverage things like distributed tracing, with integrations with Zipkin, and Appdash, and the LightStep ecosystem, and OpenTracing and all this stuff. You get to leverage circuit breakers and rate limitors and a number of other packages in there, service discovery as well. So that’s the split as I describe it.

Yeah, I was trying to figure that out, where the boundaries were for each of the things.

Yeah, and I could probably do a much better job of giving introductory, on-ramp style documentation on the website. Right now I’ve been so focused on the advanced use cases I’ve kind of let that atrophy a little bit… So I’ll put that in my queue.

Cool.

I think that we are basically out of time, but did anybody wanna talk about JBD’s new tool before we roll this thing out? Because that’s freaking cool, the gops tool. I wonder how it’s supposed to be pronounced…

Yeah, I was wondering…

I think it’s gops.

I would say gops.

It’s this really cool debug tool for Go processes on your machine. You can run gops stack and pass it the PID of a Go process and you can actually see the current stack and you can get GC information and memory statistics from a running Go process.

Yeah, it’s something I haven’t been able to use in anger yet, but I’m super excited about the potential here. Because we all know Go processes are really introspectable in theory, but I can’t be the only one when looking at something in a staging environment, for example, and having to remember how to piece together the call graph from whatever endpoints happen to be exposed. The idea of a single, unified introspection tool or interface to an arbitrary process is really exciting to me, and I’m really keen to take it to a limit at some point.

Yeah, that’s kind of the fun thing about having a runtime, is that all this stuff exists in there, you just kind of have to poke at it. I’ve only used this from poking and prodding things that are running just out of sheer curiosity and playing, but again, I look forward to trying that where I actually have a use case for it, or in the middle of debugging. I don’t wanna have to take down the process, I just wanna prod it.

I think Scott disappeared on us. Where have you been at, Scott?

[01:07:54.23] No, I’m still here. I was actually looking at the code while you were talking; it looks like you have to install an agent in the processes that you wanna introspect, so that it will open this UNIX socket in the temp directory, so that the gops program can actually go inspect things by talking over that socket. So it doesn’t seem like it’s built in quite as much…

Oh, interesting.

Yeah, we should definitely clarify that. It’s not that you can take any running Go process and do that. It works similar to the way you can expose the runtime stats over HTTP, there is kind of a library for it… But this adds more functionality than just exporting the – how’s that package pronounced? expvar, Yeah, you look at these things and you’re like… So when somebody named this, how did they pronounce it?

Pronunciation just wasn’t important at the time.

It’s like, I have two words, how do I make it one word? Here we go, expvar, I love hearing people’s pronunciations of stuff. Peter, you use Kubernetes, do you call it KubeCuttle (Kubectl)?

KubeCuttle, yeah, sure.

Yeah, I don’t do that. It’s KubeControl or Kubectl. I’ve never called it KubeCuttle, but people call it that all the time.

I like Kubectl, too. But I like KubeCuttle because it’s like a Cthulhu angle to it, which is generally how I feel when I’m programming.

So does that work for systemd too, it’s systemcuttle, and EtcdCuttle?

Yeah, exactly.

Does it make you feel better that you’re trying to diagnose something, “I’m just gonna cuttle it?” [laughs]

Well, like maps, it feels coherent to me. When I cuttle, I think like the squid, like Cthulhu coming to devour the world. And typically, when I’m debugging something, I feel like my mind is being devoured by all the bad decisions I’ve made that lead me up to that point. So it lines up, it’s what I’m saying.

[laughs] Oh… Did anybody have any other interesting projects or news they wanted to go over before we wrap the show up?

Do we have time?

Yeah, I mean… I don’t have anywhere to be.

I wanna give a shout out to GothamGo and everybody that’s in New York City this weekend. I hope everybody has a great time.

Yes… I wish I could be there. I’m traveling too much, though. Are you going, Scott or Peter?

No. I’ve been to way too many conferences recently. I need to actually get some work done.

Same.

Same here.

That’s basically where I’m at. I just got back from a conference.

Apparently, I have a few things to go through, but somebody cut me off and there is no time. There is the Go Font - the Go Team came up with this new font that’s meant for Go code. It’s on the blog, there’s a blog post about it, and it shows how the font looks like. It seems okay to me.

Oh, interesting.

Yeah.

Yeah, I hadn’t seen this.

It seems a bit… When I look at it, it feels to me antiquated, but…

It’s hard though, because I’ve never been a font zealot. There’s people who are really big into fonts, and they can look at this font and be like, “Oh, that’s this style”, when I’ve just never… It’s either easy on the eyes or it’s not. That’s as far as my font knowledge goes.

What did you think, Peter and Scott? I’m curious.

Scott, do you wanna go first?

Sure. I didn’t really spend a whole lot of time looking at it. I mean, it’s like trying to get somebody to change their religion, practically; if you want me to change the font on my editor, you’d better have a good reason. Or we can go to war. But it’s the same idea for me; I don’t have any reason even to try and adopt it. I think that the font that I use right now is fine. I’ve been using it for years and I don’t feel like that font is actually more readable for me, so… That’s where I am.

[01:12:07.23] How about you, Peter?

I guess I would classify myself as an amateur font person. I know about serifs and kerning and x-heights and all that stuff, and I actually ran the font by one of my semi-professional typeface nerds, and unfortunately there’s a lot wrong with it. The kerning is pretty bad, the differentiation in the weights is pretty bad… I mean, I don’t wanna dump on somebody’s work or anything, but it’s not a good font. It’s not great.

I’d love to see somebody explain that, because that’s the hard thing… Visually to me it’s either appealing or it’s not, and I’d love to see why, and actually get a breakdown. Our nerd brains work that way - “Okay, this is bad, but why?”

Yeah, maybe offline we can look into that.

Yeah, and maybe it’s good for some people and bad for others. It’s a matter of taste. Somebody had the taste to come up with it, and I saw a lot of people resonating with it and liking it. I’m a font illiterate, I don’t know type, so when I look at it I might get reactions that don’t do much for me, but I like the idea.

It’s hard for me, because if I change my font to anything else, I feel like I might as well just writing in a different language… Like, “What are these weird characters?” [laughs] It’s hard to get your eyes to adjust when you stare at code so much if it’s even slightly different.

Yeah, it has a great impact when you change anything. That’s why it’s so horrible when you interview and you have to code on somebody else’s computer, or a no-line editor… I totally get lost. It’s like I don’t even know what’s happening. It’s not my editor, I can’t function.

And it doesn’t have to be very far off too, to feel that out of your element; one hotkey you’re expecting doesn’t work and you’re like, “I’m ruined. I can’t code.” [laughter]

We’re very fragile creatures. [laughter]

For all the adoption of new technology that we like, we’re still very stuck in our ways.

But I think that has a lot to do with it. There’s so much change around us; we need to have a core that’s fixed.

That’s our safety blanket.

Change everything, but don’t change my environment, don’t change my editor.

Yeah, that’s true. I mean, I’m using the same editor I’ve been using for (I don’t even know) 10-15 years, something like that.

Wow.

I just can’t… I can’t cut the cord. I see new editors and I’m like, “Well, that looks cool”, and I just can’t cut the cord. I feel like, “I gotta get work done, I can’t afford to try to learn a new editor.”

So do we have anything else, or we wanna move into #FreeSoftwareFriday?

Peter, do you have any interesting projects or news to mention?

I don’t have any projects, but I kind of wanna exploit your audience for this thing that’s been bouncing around in my head a little bit lately. Can I do that, or is that totally not appropriate?

Yeah!

Please.

We all know Prometheus, right?

Oh yeah!

Yes!

…this instrumentation and monitoring service. Among its many benefits, I think one of the greatest things for me is that it’s so operationally simple. You just run the binary, it’s great for jobs, there’s no cluster, there’s no distributed file system… It just kind of does what it says on the tin. When I give the microservice workshop I say, “You should definitely be using Prometheus, because it’s so great”, but then people ask me, “What should I be using for logs?”, and as far as I know, there is a really good answer for this. I mean, most people say it it’s ELK Stack - the Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana Stack (or I guess it’s called the Elastic Stack now).

[01:15:52.09] But if you ever tried to operate an Elasticsearch cluster, you know it’s not easy. In fact, it’s notoriously difficult. So I’m wondering what a Prometheus for logs would look like - architecturally, operationally - and if maybe there’s already a product out there that I just don’t know about… I mean, I’ve done a lot of research, maybe there’s something that exists. I would love to have people ping me maybe on Twitter with their ideas.

That’s interesting. What about Go Kit Log?

Go Kit Log is about how you manage logging within your process, within the service itself. What I’m curious about is once the log information leaves the process boundary, like on STDOUT, say, how do you get that into a system that is searchable and usable, operationally simply, and without having to deal with Elasticsearch, effectively?

Okay, so are you talking about what Prometheus is for metrics, you’re talking about that for logging?

Yeah, something like that, at a very high level.

Have you looked at things like Logstash, or…?

Yeah, Logstash is like a FluentD thing where it’s pushing logs around, but it’s not actually doing any storing or querying.

Okay, so you wanna address this from the… There’s lots of stuff out there for doing metrics and alerting and things like that; you want something that’s designed specifically for logs storage. Like, if we had to rethink distributed log transfer and storage and querying today, what would that look like? Not an implementation built on something that exists, but a completely new effort - what would that look like?

Exactly. And maybe there’s already software that’s purpose-built for exactly what I’m thinking and I can just use it. If so, that’s great, I’d love to know about it. But I don’t.

But you’re talking about in Go, right? Or just in general.

Well, in general would be fine. The only thing in the space that I’m aware of that serves this need is Elasticsearch and it’s too operationally tricky, and some other reasons I won’t get into. I’m not a big fan of it for this use case, but yeah… Maybe something in Go, that would be great.

Now, Scott has a different opinion on log storage. Netflix doesn’t do a lot of the distributed logs. Do you wanna speak to that a little bit, Scott?

So I would probably need to clarify that… We do have a massive logging system; we generate a ton of logs, but I don’t… So as a company - it’s the same old joke: we’re a logging system with side effect of streaming video, and there’s a massive Kafka cluster that’s the ingest for this, and I believe that it has some processing after that and goes into…

…HTFS, I imagine.

Yeah, but my view is… I tend to try not to rely on logs, I just keep metrics around. Everything that I could possibly want to introspect.

Totally.

…and if there’s some specific thing… It’s like bucketize all unknown errors, then yeah, we’ll start logging something. But at that point there’s no performance hit because I’m gonna close the connection anyway. So yeah… That’s my little speech.

It’s difficult when you get at scale; you can’t log into the servers and check the logs anymore. You kind of have, like you said, metrics, and then you have the log messages that you wanna be alerted on, so there’s these different reasons you want logs. You want to diagnose a distributed – trace basically a request through the system and see what happened for that. You want kind of generic, aggregate summaries of things that are going on in the health of your system, which metrics solve, and you want alerts, so that when particular things happen you can be notified of them.

I think that solves most of the use cases for at-scale logging, because I think it gets too hard… Can anybody think of any other use cases that a system like this would need to solve?

[01:20:00.27] I mean, certainly… I cut the logging domain into two parts: one is your typical debug info warn application logging, where you might need this kind of deep introspection in order to debug certain issues. But you don’t need a high quality of service; you can drop some of those log messages and it’s not gonna be the end of the world. But then there’s this other thing, I call audit logging - maybe it has a different name in a different context - where it’s like, if you’re running Netflix you wanna see… Or let’s say you’re running a bank - you wanna see every time somebody makes a deposit or a credit. This stuff is critical to your business; you need durable, reliable logs of all of these transactions, and that probably needs to end up somewhere reliably.

Both of these things is sort of what I’m considering, although they are drastically different QoS guarantees.

Well, let’s talk about structured versus unstructured logging… Nah, I’m kidding. [laughter] That’s a whole show right there.

The gloves come off… [laughter] So we wanna move on to #FreeSoftwareFriday? In case we didn’t tell you, Peter…

Uh-oh…

To your point early on, that you don’t really hear from people when all is going well - we try to (in every episode) kind of just throw out a project and thank them. It does not have to be written in Go. It can be a person, group, or project, and just kind of thank them for providing stuff that makes our lives easier. If you can’t think of anything, you don’t have to, but we’ll put you as last, that way you have time to think of something.

Great, thanks.

Alright, Carlisia, do you wanna go first?

No, I don’t have anything today.

How about you, Scott?

Sure… Last week I went to QCon in San Francisco, which is a really amazing conference, actually… It was really high-quality. And I went to one talk on Twitter’s caching system, which naturally I was interested in, because I work on the Netflix caching system. They have written their own C-based cache called Pelikan, that basically speaks Memcached, but is entirely different on the inside. This talk that they gave was all about all these different things that can go wrong, which inform the design of this new cache. Their Pelikan cache is actually open source. We’ll put the link in the show notes, but I can paste it in Slack now.

There’s all kinds of things… They use a static size hash table because they used to see these latency spikes at exponentially increasing intervals, which happened to correspond with hash table extension, and a variety of things like that. The talk was really cool… Unfortunately, QCon talks take a while to come out, so it probably won’t be around for a while, but the project itself is really cool.

Oh, cool. So it was recorded? It will be out eventually?

Eventually… I don’t know when, unfortunately. I have access to the videos because I attended, but…

Oh, brag about it. [laughter] So to give you a little more time, Peter, I’ll go next. So I have not used this, I’ll preface it with this - I have not used this yet, but I was at KubeCon last week and I was talking to the CoreOS guys, and they have a really cool project called Zetcd. It’s basically a bridge between ZooKeeper wire compatible and Etcd. If you use things that are backed by ZooKeeper, like Kafka and things like that, you could actually wire this thing up in between and have it talk to Etcd instead. I thought that that was ridiculously cool, because I’ve never been fond of managing ZooKeeper clusters. I will drop that in the channel too for anybody who’s listening live.

Alright, Peter, do you have anything? Feel free to say no.

[01:24:03.21] No, I’ve got one. It’s a small thing, because sometimes the small things are the best things… I was using grep for most of my life until I stumbled over this program called ack, which was a bit more usable version of grep. And I was using that for a long time until I stumbled over this thing called The Platinum Searcher. It turns out there’s a Go implementation of it, which I’ve been using for the past couple of months with a lot of success. So I’ll also drop a link into the Slack for that one…

You can install it, and it installs this pt, and you can use it like a grep, except you don’t have to do weird contortions with -r, and grep like you expect it should work. It’s super, super fast.

I’m glad you’ve mentioned that because Dave Cheney mentioned it, and I was like “I’m gonna install it immediately”, and I never did. But now I’m gonna install it immediately. [laughs]

I’m in the same boat. I used the Silver Searcher for many years now, and it still installed, and people keep reminding me of The Platinum Searcher, and I’m like “I’m gonna use that”, and then I go along my way and continue to build stuff and I forget all about it. So now it’s gonna live in my sea of tabs until either my computer shuts down and I lose the tab, or I actually install it.

Alright, so I think with that we are out of time, and I definitely wanna thank everybody on the panel. Thank you, Scott, for stepping in, and thank you, Peter, for coming on the show. Thanks to everybody who’s listening now, and who will be listening to us when the recording is released.

Huge thank you to our sponsors, Minio and Backtrace. Definitely share the show with your friends, family, colleagues… We are @GoTimeFM on Twitter, GoTime.FM - you can go there to subscribe, and if you want to be on the show or have ideas for the show, or just questions of the hosts or guests, hit us up on github.com/gotimefm/ping. With that, goodbye everybody, we’ll see you next week.

This was fun, bye! Thanks, Peter.

Bye guys. I had a hacking good time, thanks everyone!

Hacking good time… [laughter]

Our transcripts are open source on GitHub. Improvements are welcome. 💚