Brendan Eich, founder of Brave and creator of JavaScript, joined the show to talk about the history of the web, how it has been funded, and the backstory on the early browser wars and emerging monetization models. We also talked about why big problems are hard to solve for the Internet and the tradeoffs between centralization and distribution.

Brendan Eich: We don’t know. That’s a great question. I think among the early adopters, lead users, yes they get it. A lot of them are outraged by the malvertising stories that broke this spring. And it was really great for us, because we had the late March malware on the front page of New York Times, then we had on 7th April… I woke up and there’s a letter from The Newspaper Association of America, counsels us to cease and desist, but we haven’t anything yet to actually cease and desist; those words don’t occur in the body, but it’s full of threats and crazy legal theories, including that these Newspaper Association of America members own the copyright on those ads that we would be blocking. How could they own that, because it’s malware from Russia, or whatever? They don’t own the copyright; those ads are injected by JavaScript in your browser, running on your page, communicating with third party sites with ad exchanges. Nothing to do with New York Times. There’s no creative work, ensemble work that has the ads.

I think the lawyers - it’s generally the associate GCs that join these trade groups, like Newspaper Association of America, now called The News Media Association… Newspapers have been in decades long of decline, but they view the ads as ink on paper. It’s like we’re sneaking up to grandma’s porch and we’re facing the ads that they printed on the Sunday New York Times and we’re pasting up our own ads to trick grandma into transacting with our advertisers and us getting a piece of that action.

First of all, we didn’t do any such thing. We only talked about how it can be better if we did something like that. Second of all, there’s no ink on page ad the New York Times owns. The ads are third party, they’re placed with JavaScript. Another one of my guilty legacies with JavaScript is how it’s used for third party ads.

[51:02] There’s really a deep topic here. Will people appreciate it? I think mainly people appreciate speed in browsers, they appreciate safety, and we’re leading with those. Safety is a broad term, but I include privacy. People say, “Oh, you can’t market privacy”, but you can. Snapchat built up a good cohort doing disappearing messages. People care about things like secure communications. WhatsApp’s doing end-to-end encryption.

People care after a crisis. Snowden changed things for a lot of people. I think as things evolve, we’ll have more concern about privacy. It’s often driven by crises and revelations. People just didn’t know they had a problem until they had one. So we don’t need to get too detailed on the economics, but I wanted to paint a picture because there is a lot of money exchanging hands here, a lot of middle players taking big cuts, very little for the publisher.

Brave cares about users first, and we think user attention is not fairly priced. We care about publishers, too. If you can’t keep a website a going concern, the web’s in trouble, so we’d like to see publishers get paid better. That’s where we think, if we get the right experiments done with user opt-in and publisher opt-in, we could build a better (I almost wanna call it) promotion system. The idea with advertising online now – Joe Marchese, founder of TrueX (I think Fox owns it now) said this: “You’re shotgunning people’s attention across ten thousand pages.” That means you’re wasting a lot of money, because first of all a lot of people guessed wrong, they didn’t go to that site. Then you’re retargeting them, which bugs them. You cross the line and they get an ad blocker. They’re lost to you. What if you could just get the right information at the right time, in the right place, to the person who’s likely to actually benefit from it and be happy with that marketing information? That’s the ideal model for advertising.

It solves what’s called “Wanamaker’s dilemma.” There’s this guy Jude Wanamaker who had a chain of department stores in Philly a hundred years ago, and he is alleged to have said - at least if I can get the quote right; it’s not clear if he actually said this - “My problem with advertising is half my advertising budget is wasted, I just don’t know which half.” Even then, he was shotgunning newspapers or catalog ads, and some of them missed the target.

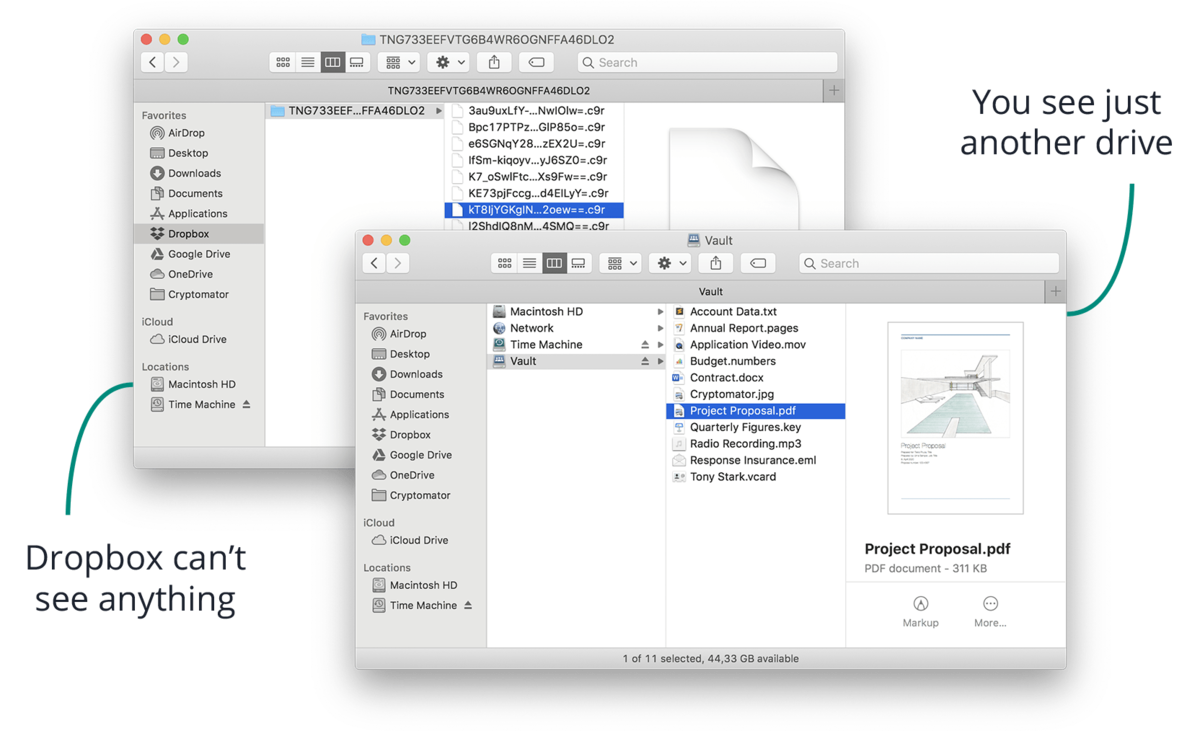

Theoretically, with a very private system like Brave where your data is kept on device - we don’t see it on our servers, we use zero-knowledge proofs to transact things like payments for donations or ad impression counts in aggregate; theoretically, you could keep that data secure; you could keep your own Facebook, your own Google, you could do your own ad business. It would be a very personal ad business; it would be a “right information at the right time” business. It would not be replacing one-for-one all those indirect ads that we block. It might even be using a different channel, like a full-screen video channel or a set-aside personal mall; some people might prefer to get an email once a week with promotions. These would be really well targeted, they wouldn’t annoy you, they would give you a deep discount, because the marketing side wouldn’t have to spend for those 10,000 ads, half of which or more (maybe 90% or more) miss the target.

[54:03] That’s the big idea with Brave. It goes to search too, because when you search with Google and Google does that great result - they’re better than Bing, as I said; they’ll probably always be better. They have the oldest data set, they have the oldest machine learning that’s co-evolved with it. But what about your keywords that you type in? That’s your data. Again, Brave’s point of view is you own your own data. Not just your browsing history, what’s visible, how you open the tab from another, where you are scrolling, but also your keyword queries to search engines. And that’s a very hot data set that you should benefit from and we should protect on your device. So we’re looking at the whole picture. And when I say anti-Google, I don’t mean that in a hostile way, I mean somebody needs to build this. In a coming world where AI is everywhere, do you really need the cloud superpowers owning all your data? From your house, your cat, your own body monitors… I think there are scale advantages to the cloud and to clustering AI calculations there, but a lot of it is personal, a lot of it could be done in your home server, or even on your phone. So there should be tiers of AI and machine learning and tiers of data, where some of that data doesn’t even leave your device. Maybe only abstracted summaries or anonymised summaries leave your device. That’s the really big vision here, and I think people will build this. I see more signs startups are doing this. Instead of building some surveillance device based on cookies or search or everything in the cloud, they’re doing local computation and doing things that can be defensively secured in your pocket or in your house. That’s where Brave gets in.